EU clubs together on energy and invites UK

- Published

"Gasmageddon" is bearing down on Europe this winter.

It may sound like the stuff of nightmares. But this is no science fiction.

The number of households facing energy poverty has doubled across the EU, according to financial services provider Allianz.

Gas shortages could drive up retail prices by 200%. Three-quarters of companies in the bloc's economic powerhouse, Germany, say they're experiencing "severe strain" from spiralling energy prices. In the UK, energy bills have gone up 80%.

The word "recession" is whispered everywhere.

Vladimir Putin is not only using conventional military weapons in Ukraine, he is also weaponising energy to try to intimidate the West, as he seeks to readjust the balance of power in Europe to Russia's favour.

On Wednesday, he railed: "We will not supply anything at all if it is contrary to our interests. No gas, no oil, no coal, no fuel oil, nothing."

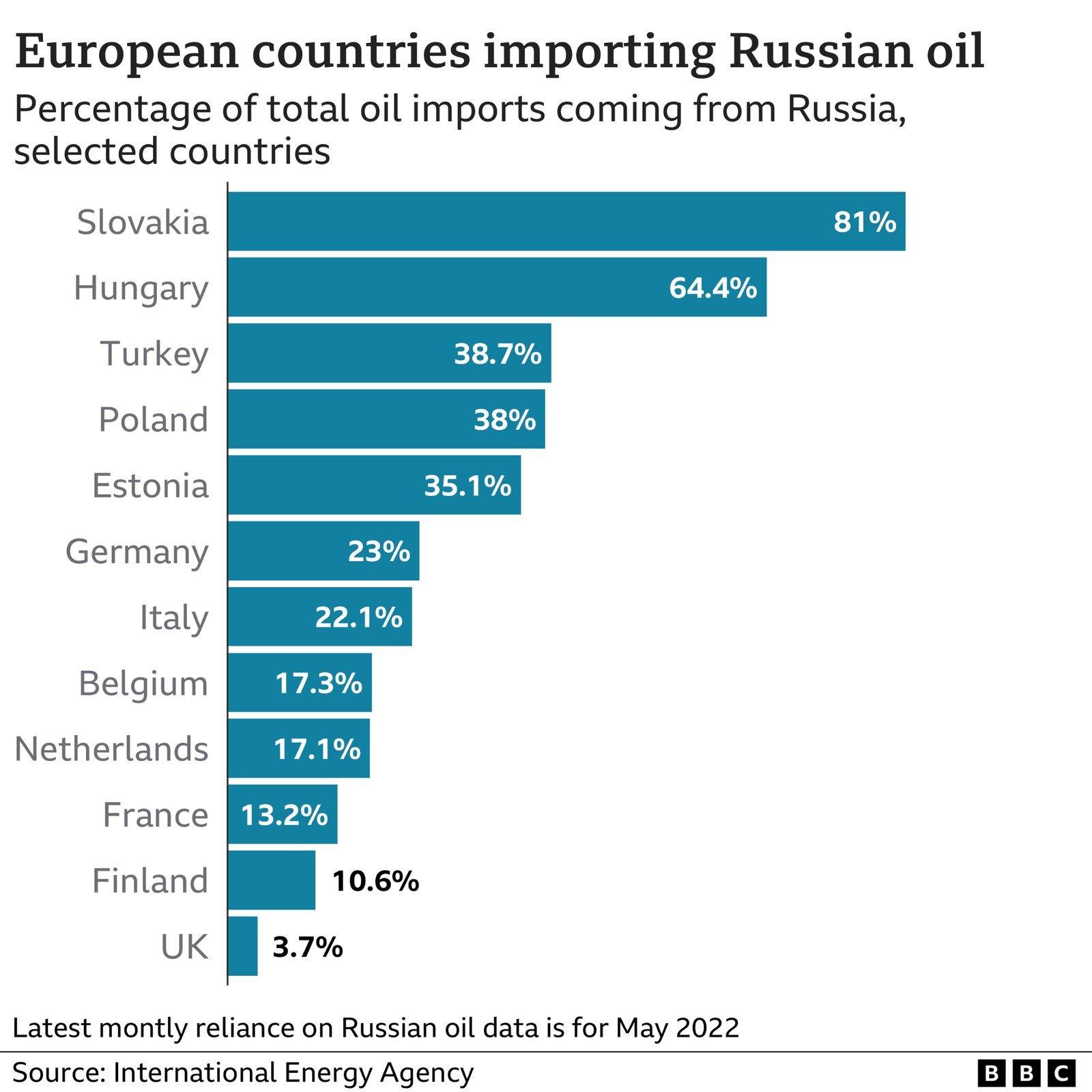

Squeezing the EU had looked to the Kremlin like a piece of cake. The bloc relied on Russia for 40% of its gas and a third of its oil before Mr Putin invaded Ukraine. Big EU powers Germany and Italy were even more dependent.

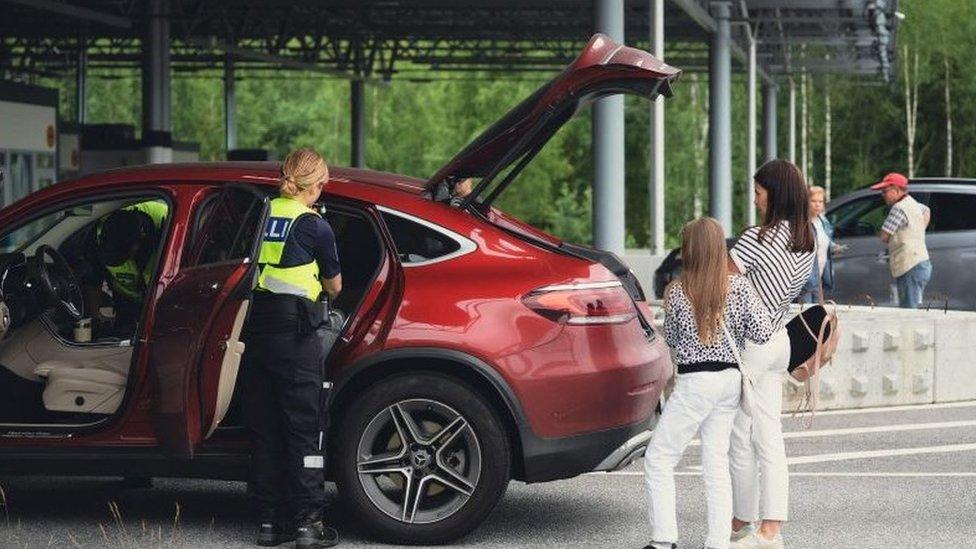

The Russian president has been switching gas supplies on and off at whim for months and the colder months are fast approaching. Even countries traditionally less reliant on Russian energy, such as France, Spain and non-EU UK, are affected by the volatility and price hikes on the global energy markets.

With businesses threatened with bankruptcy and vulnerable voters facing a choice of paying for food or fuel this winter, political and social tensions have soared alongside prices.

Prague saw mass demonstrations last weekend, with angry crowds protesting against the cost of living crisis and demanding an end to sanctions against Russia.

Bear in mind that the Czech Republic has, till now, always been hawkish towards Russia and outspoken about the need to defend Ukraine. But the economic pain at home is biting hard.

As they did at the start of the Covid crisis, EU countries tried to find their own, national, solutions.

Spain slapped limits on air conditioning in public buildings and Germany tried to discourage people from using their cars by reducing fares on public transport, while in Italy, a Nobel prize-winning physicist sparked a furious cultural debate, suggesting people could cook pasta with the heat off to save energy and cost.

A number of member states have hastily assembled financial packages to help struggling households and/or businesses. Their aim: both to reduce energy consumption and to keep costs down for consumers.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has become fond of peppering his (German-language) news conference with the English words of the song You'll Never Walk Alone, popularised by Gerry and the Pacemakers.

But the focus now is on finding a European solution. And not a few EU figures, French President Emmanuel Macron included, have said they'd love the UK to be part of a plan. More on that later.

The drive for the common EU approach is manifold. In part, it comes from the same post-Covid crisis realisation that as part of a single market, when the economies of some member states suffer, it pulls everyone down.

There's also an appreciation that there's strength in numbers. Countries such as Italy and Germany have been busy trying to find alternative energy suppliers - in Algeria and the UAE, for example. But if the EU as a whole, with its economic clout, makes the energy deal, the conditions are likely to be more favourable.

"We have to achieve that we only pay the world market price, rather than a higher price," said Mr Scholz on Wednesday. His Belgian counterpart, Alexander De Croo, pointed out that gas prices in Europe are currently double those in Asia and 10 times as much as in the US.

EU purchasing power would also avoid one member state trying to outbid another in their scramble for energy. Not a good look when it comes to EU unity.

There is, too, a very sincere desire in the EU to stop pouring energy money into Russia's war chest.

It's true, the majority of member states have drastically reduced their reliance on Russia by now. But as one very irritated EU diplomat pointed out to me, sky-high energy prices mean EU countries still pay almost the same daily amount of money to Moscow, although they currently receive so much less.

"Putin has to be roaring with laughter at us," he said.

EU energy ministers have been summoned to an emergency meeting in Brussels on Friday to discuss a raft of proposals to jointly combat the crisis.

"Russia is manipulating our energy markets," tweeted EU Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen, "[but] we have the economic strength, the political will and unity to keep the upper hand."

EU countries have already reached agreements on reducing Russian oil imports and Russian gas reliance. The Commission established joint gas purchasing capabilities back in April and planned sufficient energy storage ahead of this winter.

Proposals for this Friday include:

Mandatory targets to reduce electricity use in peak times, as that drives up electricity prices

Cap revenues of companies that make electricity using cheaper means than gas - such as nuclear or renewables. Use that windfall gain to help struggling consumers/businesses

Cap revenues of oil and gas companies, making a huge profit out of high prices. Use that windfall gain to help struggling households and invest in renewable energy sources

Help utility companies stay afloat despite market volatility

Cap Russian gas prices

But EU leaders are far from united in their priorities or energy planning. Unanimous or immediate agreement is unlikely on Friday. Germany is still iffy about capping Russian gas prices, for example. Poland wants all extra-EU gas sources to have a price cap.

And there are other tricky issues such as if/when to decouple the gas and electricity markets (a similar debate rages in the UK) and how to ensure consumers understand the long-term need to change habits and consume less energy, even if governments intervene to keep prices lower.

European Green parties are also extremely uneasy about the EU rush to replace Russian fossil fuel supplies with others elsewhere.

The German Green Party is a senior government coalition partner. Its co-chair, Robert Habeck, is deputy prime minister and economics minister.

He's been travelling cap in hand to the United Arab Emirates, keen as keen for fossil fuel deals - an irony not lost on his opponents.

German Green MEP Ska Keller admitted to me that yes, Green politicians had big plans, "but then governing happens."

She insisted that polls in Germany indicate voters understand that the Greens are being "responsible and pragmatic" in a time of energy crisis, but that they haven't forgotten the climate emergency.

European Commission energy spokesman, Tim McPhie, is quick to underline when that it comes to energy, there are "short-term fixes and longer term fixes". The EU Green Deal and climate goals are a huge source of pride in Brussels.

Mr McPhie says long-term European security is not about replacing Russian gas with gas from somewhere else - it's about renewables' energy efficiency.

And what about that invitation for UK co-operation on energy that I mentioned earlier, repeated to me again this week by the French Europe Minister, Laurence Boone?

Her predecessor, Nathalie Loiseau, says that in these times of crisis, co-operation makes more sense than post-Brexit "splendid isolation".

But while it could make economic sense for the UK to join together with the EU to try to benefit from lower prices on the global market, new PM Liz Truss, even if tempted, might find that co-operation politically awkward with some parts of her Conservative party.

There is, though, an aspect of energy and the EU that Prime Minister Truss won't be able to ignore. And that's to do with Northern Ireland.

The island of Ireland has a single electricity market, interconnected to Great Britain, says Mary Starks, former director at GB energy regulator Ofgem, now energy specialist at Flint.

But the Republic of Ireland is an EU member state, theoretically subject to EU common energy regulations.

"So what this means for both Northern Ireland and the Republic will come into focus at some point," says Ms Starks.

And if wholesale energy prices are successfully reduced on one side of the Channel, but not the other?

Ms Starks told me that normally, energy flows very freely across electricity and gas interconnectors, but if the EU, for example, managed to lower prices before the UK, then Brussels would "need to take steps to ensure its cheaper power and gas did not 'leak' to the UK".

While Ms Starks says it would be highly unlikely that the EU would shut the interconnectors unilaterally, there would have to be some sort of regulation of trading and flows, in order to prevent leakage.

And that would necessitate dialogue.

- Published7 September 2022

- Published3 September 2022

- Published7 September 2022

- Published23 February 2024

- Published2 September 2022

- Published6 September 2022