Beyond the US midterms: The Swiss answer to congressional gridlock

- Published

It's notoriously hard to get new laws passed in the US and few believe the looming election reshaping Congress will solve that. Could the Swiss "people power" model help?

The US political system seems designed to create gridlock. The two chambers of Congress are frequently controlled by different parties.

The Senate has longstanding procedures that allow the minority party there to block most major legislation that doesn't have the support of at least 60 of the 100 senators.

And anything passed by Congress can be vetoed by a president (overriding that requires a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate).

All this means that the political stars have to align for the federal government to get things done - even overwhelmingly popular laws will wither on the congressional vine.

Policies like raising the minimum wage, enacting gun control legislation or immigration reform have substantial support but go nowhere in Washington.

That has left some Americans frustrated - by a two-to-one margin they believe the nation is heading in the wrong direction.

Wouldn't it be great if citizens could decide new policy, and the government would carry it out?

So what happens in Switzerland?

Nearly all major policy is decided at the ballot box.

Voters go to the polls four times a year in nationwide votes. In 2022 they have been asked to decide on 11 different issues, from a complete ban on animal testing (rejected) to raising the retirement age for women (approved).

There are also regular ballots at regional and even village level to decide on local issues.

In the Middle Ages, the Swiss were already doing things a little differently - while their neighbours had feudal lords with absolute power, some Swiss regions had "landsgemeinde" in which citizens gathered in the town square to make policy.

The only requirements for being able to vote? Carrying a sword and being male (of which more later).

This "bottom up" way of governing came to be viewed as essential if Switzerland was to survive and thrive.

A vote on pension reform was held earlier this year

It's a small country, but very diverse - four national languages (German, French, Italian, and Romantsch). You have remote farming communities high in the Alps and urban centres in Zurich or Geneva.

Everyone, the thinking goes, needs to feel their voice is heard.

So how does it work?

Let's say you'd like to give all workers longer vacations.

Draft your proposal, gather 100,000 signatures from fellow citizens, and a nationwide referendum will take place.

This happened in 2012 when voters rejected a proposal to increase statutory holiday after business leaders warned it would be too expensive.

Or, let's say you're not happy with new legislation that parliament has already passed. Here, you only need 50,000 signatures, and the proposed law will go before the people. But this slows things down.

Swiss women only got the right to vote in 1971, shockingly late compared with the rest of Europe and it took not one but two nationwide ballots, which only men could participate in.

Swiss women first had the vote in 1971

Many Swiss women I know grew up with mothers who campaigned for years for the right to vote.

"One of the arguments against was that women's brains were too small," journalist Gaby Ochsenbein remembered. "Seriously, that's what they said."

Today, she believes, the power a vote in Switzerland can have encourages participation. "I've never missed a vote, and my daughters neither."

What other disadvantages are there?

Some Swiss are worried the system is open to abuse.

Since it only takes 100,000 signatures to force a referendum, an awful lot of things are ending up at the ballot box.

Some are fairly harmless, like one man's campaign for subsidies for farmers who let their cows keep their horns. This was rejected in 2018.

But others, some analysts argue, are simply vehicles for political parties to keep their agenda in the public eye. The rightwing Swiss People's Party regularly gathers enough signatures to have votes on immigration related issues.

Voter fatigue is also a risk when there are so many, often complex, decisions to make. In local votes the turnout can be lower than 30%.

More on this series, Seeking A Solution

As Americans prepare to vote we are visiting countries around the world looking for answers to challenges facing the US political system

We are tackling subjects like an ageing Congress, gridlock in passing laws, a lack of female representation and low turnout

Reporters in Norway, Bolivia, Finland, Australia and Switzerland will explain how these issues are handled where they live

What do the Swiss think of it all?

But ask a Swiss citizen if they would give up their unusual system and the vast majority will say no.

Some will suggest changes to it such as increasing the number of signatures required, but abandoning the system altogether is unthinkable.

"Direct democracy is there for the population to check the parliament," says a colleague. "And it's also a way to bring the interests of the general population into the political system."

The system supports neutral Switzerland's long tradition of consensus. There are no bitter confrontational battles between the big political parties; the role of government is to carry out the wishes of the people, as expressed through the ballot box.

Politicians are not allowed to get too big for their boots here, and that's just the way the Swiss like it.

Could it work in the US?

Although there is nothing like the Swiss referendum system on the national level in the US, similar processes are fairly common on the state and local level.

In recent years, states have decriminalised marijuana, raised the minimum wage, enacted electoral reforms and legalised gambling through ballot measures.

In the early 2000s conservatives pushed to ban gay marriage. This year, liberals have begun a move to put abortion protections on state ballots.

California, whose population is more than four times that of Switzerland's, is the state probably best known for its use of ballot measures.

The system there, however, has proven to be somewhat unwieldy.

Critics say the language of ballot proposals is frequently confusing or misleading. And some enacted policies like mandatory spending on public schools have made it harder to craft workable state budgets. Others have resulted in lengthy legal disputes and enflamed political divisions.

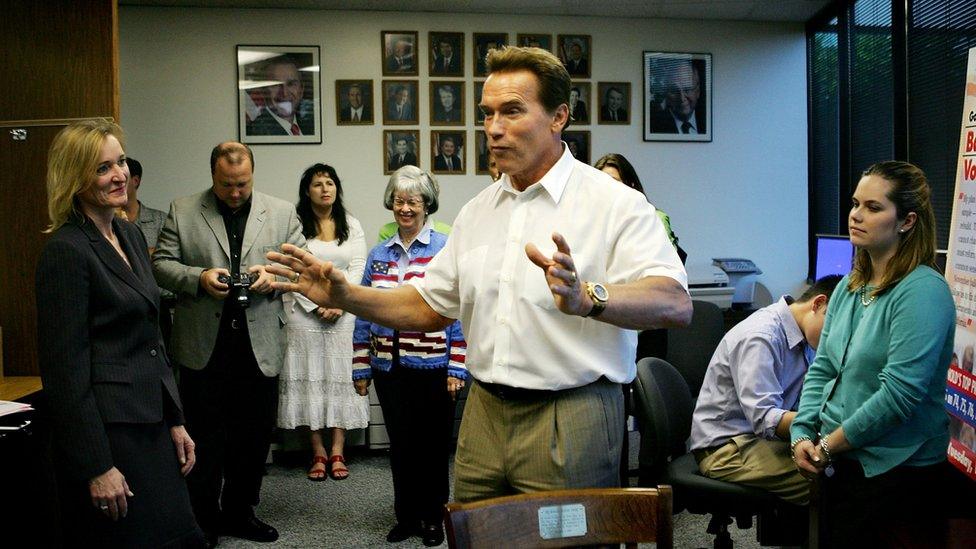

Arnold Schwarzenegger campaigns for his ballot measures in 2005 when California governor

Battles over ballot measures frequently involve multi-million-dollar advertising campaigns that greatly simplify what can be complex policy issues and leave voters even more unsure over what is actually at stake.

All these concerns could be magnified if referendums were conducted among a national voting population of 257 million Americans.

The US system that makes it challenging to enact major legislative policies is difficult by design - because the crafters of the US Constitution had a distrust for centralised government power.

There are plenty of Americans who still like it that way. Opposition to "big-government" policies is a central tenet of American conservatism.

The US is a massive, continental nation and many residents in Republican-controlled states in the US heartland and West don't want their politics dictated from far-off Washington - or from the millions of voters in coastal metropolitan cities via a referendum system.

Read more about US midterms

EXPLAINER: What are midterms and who's being elected?

ANALYSIS: Five reasons why these elections matter

ON-THE-GROUND: The voters who see a coming storm