Ukraine war: Russian activist writes letters from jail

- Published

Vladimir Kara-Murza was imprisoned in April for criticising Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine

When Vladimir Kara-Murza announced he was returning to Moscow earlier this year, his wife Evgenia knew the risk but did not try to stop him.

Russia had invaded Ukraine and made it a crime to call it a war. Thousands of protesters had been arrested. Vladimir himself was a sworn opponent of President Vladimir Putin and an outspoken critic of atrocities committed by his military.

Still, the opposition activist insisted on being in Russia.

Now he has been locked up and charged with treason and Evgenia has not been allowed to speak to him since April.

But in a series of letters to me from Detention Centre No. 5, Vladimir - who has twice been the victim of a mysterious poisoning - says he has no regrets, because the "price of silence is unacceptable".

Opposing President Putin was dangerous even before the invasion, but since then the repression of dissent has intensified. Almost all prominent critics have either been arrested or left the country. Even so, the treatment of Vladimir is especially harsh.

All the charges against him are for speaking out against the war and against President Putin and yet his lawyer calculates he could spend 24 years behind bars.

"We all understand the risk of opposition activity in Russia. But I couldn't stay silent in the face of what's happening, because silence is a form of complicity," Vladimir explains in a letter from his cell.

He felt he could not stay abroad either. "I didn't think I had the right to continue my political activity, to call other people to action, if I was sitting safely somewhere else."

'I could kill him'

The first Evgenia heard of her husband's arrest was a call from his lawyer, who had been tracking the activist's phone as he always did when his client and friend was in town. On 11 April, the phone had come to a stop at a Moscow police station.

Vladimir was eventually allowed to call his wife, who lives in the US with their children for safety. There was just time to say: "Don't worry!"

Evgenia smiles at the absurdity of that instruction.

The couple were children of perestroika, growing up during Russia's democratic awakening after the Soviet collapse. Vladimir then studied history at Cambridge, and simultaneously began a career in Russian politics as an adviser to the young reformer Boris Nemtsov.

This is the longest the pair have been apart since their marriage on Valentine's Day in 2004 and the activist says not seeing his family is the hardest thing. "I think about them every minute of every day and cannot imagine what they're going through," he says.

"I love and hate this man for his incredible integrity," Evgenia told me on a recent trip to London.

"He had to be there with those people who went out on the streets and were arrested," she said, referring to the many Russians detained for opposing the war. "He wanted to show that you shouldn't be afraid in the face of that evil and I deeply respect and admire him for that. And I could kill him!"

Evgenia has not been allowed to speak to her husband since he was jailed

Vladimir was initially detained for disobeying a police officer, but once in custody the serious charges began raining down.

The activist was first accused of "spreading false information" about Russia's military and "higher leadership".

The rights group OVD-Info has recorded more than 100 prosecutions under that so-called "fake news" law since the war began: a local councillor, Alexei Gorinov, was sentenced to seven years in July and activist Ilya Yashin will go on trial soon after referring to the murder of civilians in Bucha.

Vladimir's case is based on a speech in Arizona where he said Russia was committing war crimes in Ukraine with cluster bombs in residential areas and "the bombing of maternity hospitals and schools".

That has all been independently documented, but according to the charge sheet I have seen, Russian investigators deem his statements to be false because the defence ministry "does not permit the use of banned means… of conducting war" and insists that Ukraine's civilian population "is not a target".

The facts on the ground are ignored.

Another charge stems from an event for political prisoners at which the activist referred to what investigators term Russia's "supposedly repressive policies".

Then last month he was charged with state treason.

The activist responded to that in his latest letter: "The Kremlin wants to portray Putin's opponents as traitors… the real traitors are those who are destroying the well-being, the reputation, and the future of our country for the sake of their personal power, not those who are speaking out against it."

Political persecution

The treason charge is based on three speeches abroad, including one in which Vladimir said that in Russia political opponents were persecuted.

Investigators maintain that he was speaking on behalf of the US-based Free Russia Foundation, which is banned in Russia, where any "consultancy" or "assistance" to a foreign organisation considered a security threat can now be classed as treason.

No secrets have to be divulged.

"State treason for public speeches? That's just absurd. It's quite simply persecution for free speech. For opinion. Not for any real crime," Vladimir's lawyer, Vadim Prokhorov, argues by phone from Moscow.

He says the activist had no link to the foundation at the time.

"This is a political case. They're trying to stigmatise the absolutely normal, civilised Russian opposition."

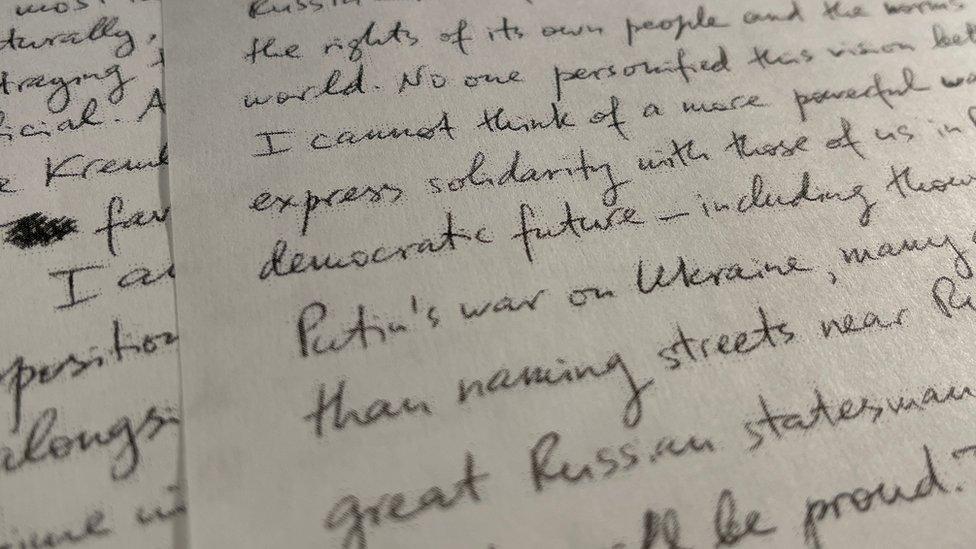

Vladimir has written to the BBC from his jail cell

Vladimir himself points out that the last person accused of treason for political opposition was the Nobel Prize-winning writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 1974. "All I can say is that I am honoured to be in such company."

Evgenia finds it harder to sound so calm.

This is not the first time she has been scared for her husband. He nearly died, twice, in Moscow, and the cause of his poisoning has never been identified.

When he first collapsed in 2015 and slipped into a coma, Evgenia was told he had a 5% chance of survival, but he defied the odds.

She nursed him back to health, helping him learn to function again, even to hold a spoon. He would then insist on working on his laptop on their couch, despite being sick every half hour.

"The moment he could walk, he packed his bags and went to Russia. That fight is bigger than his fears."

For Evgenia, that has meant seven years sleeping with her phone, ''afraid I will get that call from him, or from someone else because he can't talk anymore".

She gave up persuading her husband not to go to Moscow long ago: her only protest was to refuse to help pack his bags. But before his last visit, after the war started, Evgenia accompanied him first to France.

"I wanted to make the trip beautiful," she remembers, forcing back tears as she recalls long strolls through the streets of Paris, talking endlessly. "Deep inside, I knew what was coming."

Nemtsov's Place

Since Vladimir's arrest, Evgenia has taken on his advocacy work: speaking out about the war in Ukraine and political repression in Russia, as well as her husband's case.

On Monday she will unveil the Boris Nemtsov Place in London, the result of a long campaign by Vladimir to honour his mentor and friend. The prominent opposition politician was shot beside the Kremlin in 2015 in a contract killing for which the contractor has never been caught.

The renamed London street, actually a roundabout, is close to the Russian trade delegation in Highgate.

Boris Nemtsov (left) was a friend and mentor to Vladimir (right)

"The idea was that every car that comes to the big gate will see the Boris Nemtsov plaque," Evgenia explains. Her husband hopes a different Russia will one day be proud of that name.

For several years, the politician worked closely with Vladimir to lobby Western governments to sanction senior Russian officials for human rights violations. Their success infuriated a political elite that had enjoyed travelling abroad and channelling funds there.

In Moscow once, Vladimir told me he had concluded that those "Magnitsky" sanctions are why both he and Mr Nemtsov were targeted.

Standing-in for her husband is taking a heavy toll on Evgenia, but it is also kept her going.

"I am doing what I need to do so that he can be brought back to the kids and this hideous war stops and this murderous regime can be brought to justice."

Vladimir is not staying silent, either.

His long, handwritten prison letters set out his convictions that Russia is not doomed to autocracy and its people are not all brainwashed Putin devotees.

He points to the large number of letters he gets from supporters who openly criticise the Ukraine invasion and the Kremlin, and to those who still protest publicly, despite the risk. He urges the West not to isolate that part of Russian society that "wants a different future for our country".

He also warns that the Ukraine war will not stop whilst Vladimir Putin remains in power.

"For Putin, compromise is a sign of weakness and an invitation to further aggression," he says. "If he's allowed a face-saving exit from the war, then in a year or two we will have another one."

Vladimir tells me he is coping with imprisonment with a mixture of exercise and prayer, books and letters. As a historian, he has a particular interest in Soviet-era dissidents and has been reading more about them as he awaits trial.

"Their favourite toast back then was 'To the success of our hopeless cause!'" he writes. "But as we know, it wasn't so hopeless after all."

- Published11 November 2022

- Published8 November 2022

- Published2 November 2022