Brussels attacks: Trial begins over 2016 attacks that killed 32

- Published

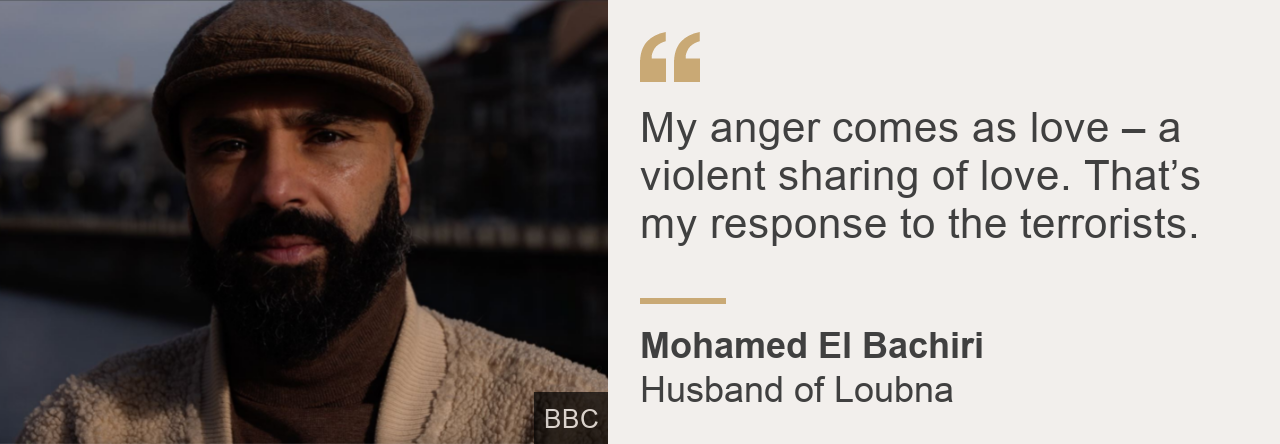

Mohamed El Bachiri lost his wife Loubna in the 2016 Brussels attacks

On a bridge overlooking a Brussels canal, Mohamed El Bachiri's face lights up in the winter sun as he remembers the mum of his three boys.

"Loubna was an angel, she was beautiful, she was always smiling, she was an extraordinary mother and wife," says Mohamed.

Thirty-four-year-old teacher Loubna Lafquiri was murdered on the Brussels metro on the morning of 22 March 2016.

In all, 32 people were killed by three suicide bombers in the attacks at Maelbeek station and Zaventem airport.

Ten men are now going on trial in the Belgian capital. Six of them have already been found guilty of involvement in the terror attacks in Paris in November 2015, which killed 130 people.

Salah Abdeslam, the main suspect in the French trial who was detained four days before the Brussels attacks, is also among the defendants, along with others whom prosecutors claim hosted or helped certain attackers.

One of the 10, who is presumed killed in Syria, will be tried in absentia.

Back in 2016, Mohamed El Bachiri was plunged into grief with the realisation he was now a widowed father to three children under the age of 10.

His immediate response? A Jihad of Love.

This, the name of the book he subsequently wrote, was intended to wrestle back the narrative from men who had grown up in his community and who had corrupted his Islamic faith.

"I needed to express a kind of anger - which is legitimate. My anger expresses itself in the jihad [struggle] of love. Sharing love. That's my way of violently responding to the terrorists. To deconstruct their ideology."

I meet Mohamed in Molenbeek, one of the poorest districts of Brussels. It is where plotters of both the 2016 Brussels bombings and the Paris attacks had lived and were later given refuge amid a huge manhunt.

Whenever such high-profile cases come to court, we the media often talk of an opportunity for justice to finally be done, or a moment where bereaved families can "move on."

But Mohamed will not be attending the trial.

"I have three kids who really need my energy, who need strength," says Mohamed. "It's not always obvious, but I really need to protect myself and I am sincerely afraid what the legal process might reawaken in me."

Does he ever allow himself to think about those who took away the "love of his life"?

"I think those men on trial, their thoughts are in hatred and darkness and negativity. And to wish them ill - I hold to the principles of humanism and I can't wish suffering on others. I don't have hatred, it brings nothing to your life. How to react to this is with a message of peace and love and not to be sad or negative."

As I and my Brussels colleagues began to think about how we would cover this trial in our adopted city, we considered which of the 32 bereaved families we would try to approach to ask if they felt able to talk.

Mohamed was an obvious choice, as a father of three who still lives in the community where some of the killers had plotted. So too was Charlotte Dixon-Sutcliffe, whose partner David was the only Briton murdered in the Brussels attacks; in early 2016, she and David had been living in Brussels with their son Henry, who was turning seven.

What none of us knew was that an immediate, profound bond had been forged between Mohamed and Charlotte in the hours after the attacks, as photos of their respective missing loved ones David and Loubna circulated online.

"On my Facebook they always appeared next to each other and I was invested in her," says Charlotte.

"She was just so beautiful and she was with her three children. Her eyes were shining through the photograph."

In a park overlooking the River Thames in London, Charlotte tells her story with the same illuminated expression that Mohamed had when also describing Loubna.

"I just felt really attached to her and almost like - and this may sound ridiculous - but almost like their fates were intertwined."

Charlotte lived with David and their son Henry in Brussels before David's death

Charlotte says the connection with Loubna was overwhelming.

"It was almost like I was as invested in her being found as it was David. It's like she became a family member or someone that I cared about, even though I had never met her. It was heartbreaking for me with David. But it felt like I'd lost her as well."

For Charlotte, her treatment by the Belgian authorities had compounded her trauma as she had searched in vain for her partner.

"With my picture of David we were going into local police stations and they were gathering round and just saying, 'Well, it's nothing to do with us, it's a federal matter'," she says.

Three days after the attack, Charlotte got a call from a police social worker:

"It was dark. I was walking the dog around the streets. She said I had to prepare myself for the worst now. She basically told me that David was dead. She told me over the phone."

Charlotte says the authorities became more supportive recently.

Much like how Mohamed channelled his grief into writing his book and sharing his message in schools, Charlotte founded an organisation called Survivors Against Terror.

"One of the big drives is to make sure that terrorist acts don't happen in the first instance. But if they do, having seen the poor treatment and some of the excellent treatment, it instils a massively strong drive to make a difference and to change things so that no one has to suffer in the way that we did."

Defendants were surrounded by special police as the trial began on Monday

After the attacks, she and her son Henry left Belgium to try to rebuild their lives but Charlotte has decided to return to Brussels for the start of the trial.

The defendants include Mohamed Abrini, who prosecutors say is the "man in the hat" who was captured on CCTV fleeing the airport after his suitcase of explosives failed to detonate.

"So many of them have already been found guilty and are serving sentences. But I think they weren't the only ones. I think that there was a huge misstep in the way that the Belgian state handled the attacks, [how it] behaved on the day of the attack and leading up to the attack."

Charlotte points to intelligence failings in the run up to the attack and the decision to keep the metro running after the earlier airport bombings.

There were government resignations and apologies in the aftermath, but that is not enough for many bereaved families and survivors.

"Culpability obviously essentially rests with those who committed the attacks, but certainly there's a level of culpability by the Belgian state that I feel needs to be addressed," says Charlotte.

As well as shining a light on how the authorities acted, Charlotte welcomes the opportunity to give a victim impact statement.

"Me being able to present a picture of David in court will give me some peace. It will give me something that will help me connect a sense of justice for him."

She doesn't want her partner remembered as just one of 32 victims.

"David was incredibly funny, the power he had to be able to connect to other people, to be able to bring joy to people's lives - it's like it's the very polar opposite of the people in those boxes."

That's a reference to the glass boxes for the defendants in the specially constructed court at the former Nato headquarters where the trial will slowly play out over the next six months.

In September, the judge ruled the boxes should be reworked after defence lawyers argued they were like animal cages.

A barrister speaks to a defendant through a glass shield

In all, the delayed trial is expected to cost up to 25 million euros ($25.9m; £21.5m).

In the greyness of the court and the grind of the legal process, Charlotte hopes her depiction of her David will provide some colour.

"I hope that joy stays with him. And I think maybe if I could bring to that place a sense of lightness and connection and love and happiness, then that's got to be something, doesn't it?"

In the course of this working on this story we discovered the bond Charlotte felt for Loubna was reciprocated.

When we had said our goodbyes to Mohamed, I asked if he was particularly attached to any of the other families of the victims.

"There was a British woman. She had a young boy and also lost her partner."

When I explain we are also interviewing Charlotte and she is returning to his city for the trial a smile breaks out across his face.

Neither knows how they will react to the coming months but both hope to meet each other and reinforce the solidarity and spirit the terrorists unwittingly created.

"They've created a network of people that talk about cohesion and love and community," says Charlotte.

"They destroyed some of us, but we come together and we're stronger. You know what? Our message is stronger. And that's why they won't win."

Related topics

- Published15 April 2016

- Published12 March 2021

- Published9 April 2016