Turkish elections: Simple guide to Erdogan's fight to stay in power

- Published

President Erdogan's powers have increased dramatically since he first led Turkey in 2003

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been in power for more than 20 years and he is favourite to win five more, having narrowly missed out on a first-round victory.

Turkey is a Nato member state of 85 million people, so it matters who is president both to the West and to Turkey's other partners including Russia.

Mr Erdogan's opponent in a second-round run-off on 28 May is Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who was backed by six opposition parties and won almost 45% of the vote - some 2.5 million votes less than his rival.

Turkey has become increasingly authoritarian under President Erdogan and this was the opposition's biggest chance yet to defeat him, with Turks struggling with soaring inflation and reeling from twin earthquakes that have left more than 50,000 people dead.

Whoever wins the vote on 28 May will win the presidency.

Erdogan's advantage

His AK Party has been in power since November 2002, and he has ruled Turkey since 2003.

Although Turkey's 64 million voters are deeply polarised, the 69-year-old leader has an in-built advantage over his rival.

Mr Erdogan's allies control most mainstream media, to the extent that state TV gave the president 32 hours and 42 minutes of air time and his challenger just 32 minutes, at the height of the campaign in April.

Monitors from the international observer group OSCE said there was an unlevel playing field and biased coverage in Turkey's vote, even if voters had genuine political alternatives.

Initially Mr Erdogan was prime minister, but he then became president in 2014, running the country from a vast palace in Ankara. He responded to a failed 2016 coup by dramatically increasing his powers and cracking down on dissent.

Leading Kurdish politicians have been jailed and other opposition figures threatened with a political ban.

But this election was the opposition's biggest hope of unseating the president yet.

Increasing numbers of Turks have blamed him for rampant inflation of 44%, and academics say the real rate is far higher than that.

He and his ruling AK Party were widely criticised for their response to the double earthquakes in February that left millions of Turks homeless in 11 provinces.

And yet most of the cities which are considered Erdogan strongholds still gave him 60% of the vote.

His party is rooted in political Islam, but he has forged an alliance with the ultra-nationalist MHP.

Six opposition parties - one candidate

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, 74, is an unlikely choice of candidate to unseat the president.

He is seen as a mild-mannered and bookish opponent and presided over a string of election defeats at the helm of the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP).

He polled well in the first round, taking Mr Erdogan to his first run-off, but not as well as the opinion polls had indicated he would.

Mr Kilicdaroglu secured the backing of six opposition parties, including the nationalist Good party and four smaller groups, which include two former Erdogan allies one of whom co-founded the AK Party.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu has agreed that the leaders of his alliance will all share the role of vice president

He also has the support of Turkey's second-biggest opposition party, the pro-Kurdish HDP, whose co-leader described the elections as "the most crucial in Turkey's history".

His biggest hope of snatching victory from a president buoyant after his first-round lead lies in increasing the support of both nationalist and Kurdish voters. A difficult feat when Turkey's nationalists want the next president to take a tougher line on Kurdish militants.

In the lead-up to the second round, he made a clear pitch to nationalist voters, banging his fists on the table and vowing to send home 3.5 million Syrian refugees. This was already his policy, but now he has decided to make a big point of it.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu's selection was not universally popular as the mayors of Istanbul and Ankara were potentially stronger candidates. Both are party colleagues who took control of Turkey's two biggest cities in 2019 for the CHP for the first time since 1994.

He is also a member of Turkey's Alevi minority, and when the opposition candidate drew attention to his roots Mr Erdogan accused him of seeking to exploit it.

His Nation Alliance, also known as the Table of Six, are united in their desire to return Turkey from the presidential system created under Mr Erdogan to one led by parliament.

The leaders of the other five members of the alliance have agreed to take on the roles of vice-president. But even if they were to win the presidency, the Erdogan alliance won a majority in parliament on 14 May and would make reforms very difficult.

Fight for remaining votes

Turnout in the first round was already very high at almost 89% among voters in Turkey.

If Mr Kilicdaroglu is to make up the 2.5 million votes between him and President Erdogan, he will need to win over voters who backed ultranationalist candidate Sinan Ogan who came third in the first round with 2.8 million votes.

That task was made even harder when Mr Ogan endorsed the president.

His demand is for a tougher stance on tackling Kurdish militants and returning Syrian refugees.

Mr Kilicdaroglu had already adopted a more strident tone on Syrians since the first round, promising to "send away" all refugees as soon as he came to power.

Reacting to Mr Ogan's decision to back his rival, he said the vote was now a referendum: "We are coming to save this country from terrorism and refugees."

President Erdogan said he had made no deals with Mr Ogan: 450,000 refugees had already returned home and the plan was to send back another million, he said.

Who controls parliament?

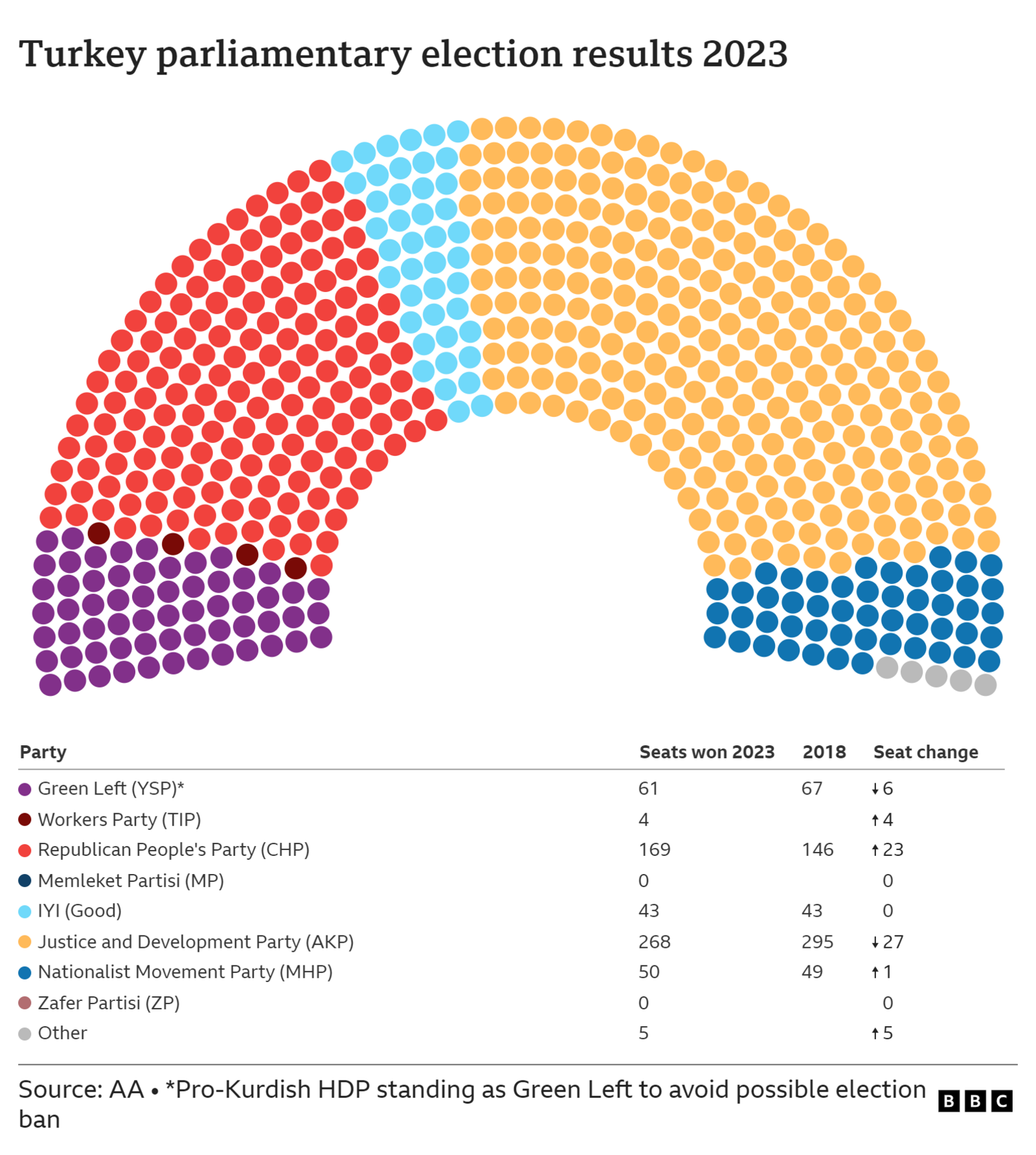

The ruling AK Party of Recep Tayyip Erdogan has forged an alliance with the nationalist MHP and together they have secured a majority of 322 seats in the 600-seat parliament, down on five years ago.

Parties tend to form alliances because they need a minimum of 7% support to enter parliament.

The six-party opposition wants to change that but its Nation Alliance only managed 212 seats.

The pro-Kurdish party ran under the banner of the Green Left to avoid a potential election ban, and came third with 61 seats.

Under the Erdogan reforms, it is now the president who chooses the government, so there is no prime minister.

Erdogan's future

Under Turkey's revamped constitution allowing only two terms as president, Mr Erdogan would have to stand down in 2028 if he won the 28 May run-off. There are currently no plans for a successor.

He has already served two terms but Turkey's YSK election board ruled that his first term should be seen as starting not in 2014 but in 2018, when the new presidential system began with elections for parliament and president on the same day.

Opposition politicians had earlier asked the YSK to block his candidacy.

What do the two candidates offer?

Under an Erdogan presidency, Turkey can expect increased control of state institutions and the media and a greater crackdown on dissent. Inflation is likely to remain high because of his preference for low interest rates.

Internationally, he could continue to resist Sweden's bid to join Nato and will paint himself as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia.

Mr Kilicdaroglu and his allies want to remove the president's right to veto legislation, cutting the post's ties to political parties and making it electable every seven years.

He wants to bring inflation down to 10% and send 3.5 million Syrian refugees home. President Erdogan has promised to speed up the voluntary repatriation of a million Syrians.

Mr Kilicdaroglu also wants kickstart Turkey's decades-long bid to join the European Union and restore "mutual trust" with the US, after years of fractious relations during the Erdogan years.

- Published6 March 2023

- Published24 March

- Published4 July 2022

- Published9 February 2023