Turkey election: What five more years of Erdogan would mean

- Published

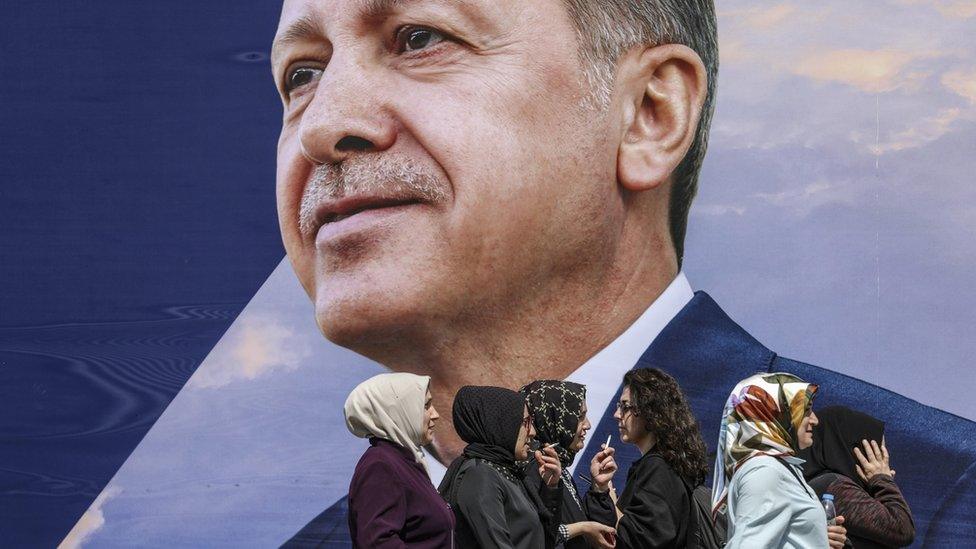

Supporters of President Erdogan say he has improved their daily lives

After two decades in power and more than a dozen elections, Turkey's authoritarian leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan knows how to work a room. At a taxi drivers' convention in Istanbul, they could not get enough of him.

He controlled the crowd like the conductor of an orchestra. They cheered and clapped - and booed the opposition - on cue. The venue was a waterside convention centre in Istanbul, built during his time as mayor of the city.

The rally reached a crescendo as the president delivered his parting shot: "One Nation, One Flag, One Motherland, One State." By then, many aging drivers were on their feet, punching the air or raising one arm in a salute.

Ayse Ozdogan, a conservatively dressed woman in a headscarf, had come early with her taxi driver husband to hear her leader's every word. A crutch rested on the seat next to her. She struggles to walk but could not stay away.

"Erdogan is everything to me," she said, with a broad smile. "We could not get to hospitals before, but now we can get around easily. We have transportation. We have everything. He has improved roads. He has built mosques. He has developed the country with high-speed trains and underground lines."

Skyrocketing food prices have hit people in Turkey

The president's nationalist message appealed to many in the crowd, including Kadir Kavlioglu, aged 58, who has been driving a minibus for 40 years. "Since we love our homeland and our nation, we are walking steadily behind the president."

"We are with him every step of the way," he said, "whether the price of potatoes and onions rises or falls. My dear president is our hope."

When Turks went to the polls earlier this month, they were not voting with their wallets. Food prices are skyrocketing. Inflation is at a punishing 43%.

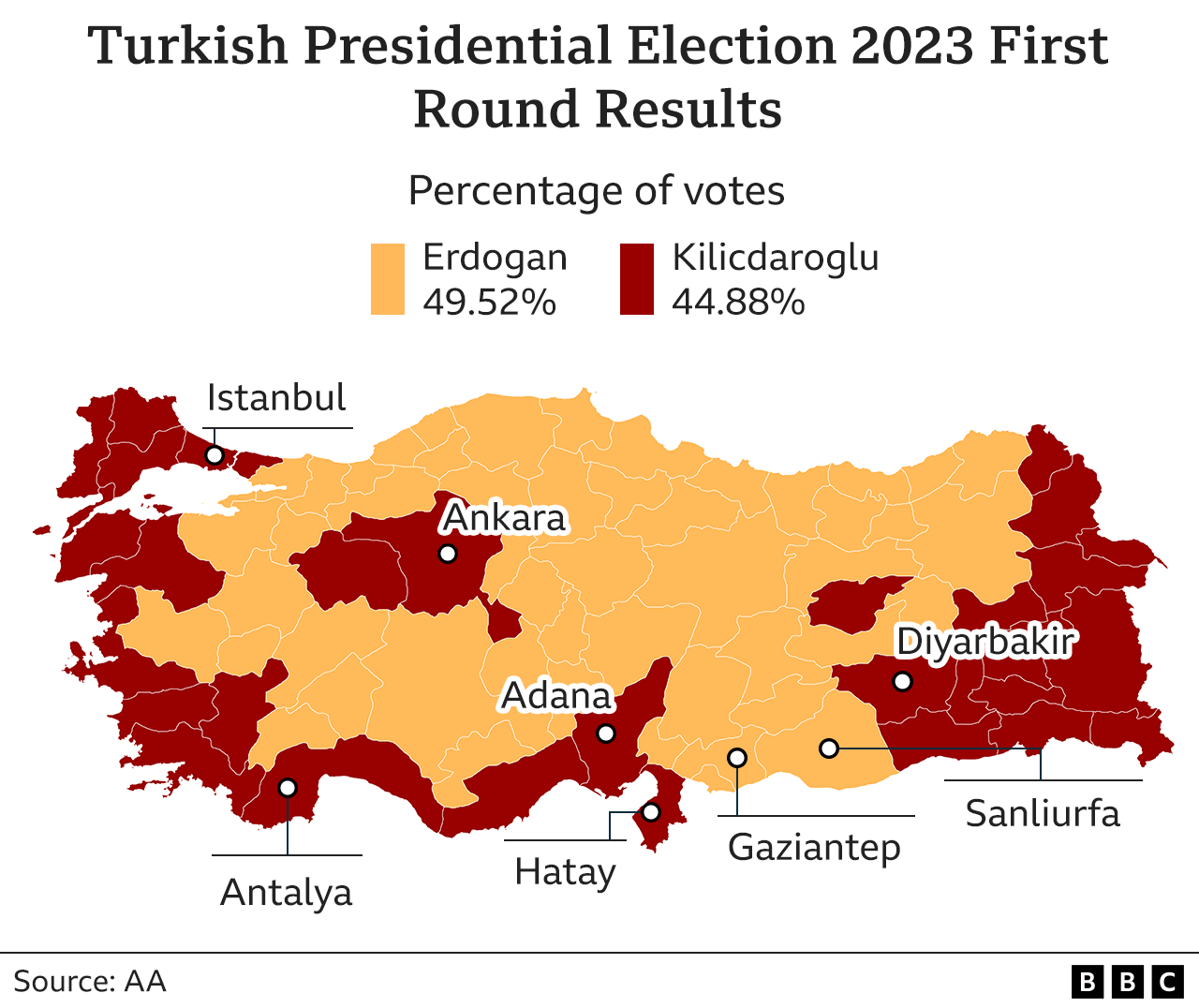

Yet President Recep Tayyip Erdogan - who controls the economy and much else here - came out in front with 49.5% of the vote. That confounded analysts and taught a lesson here - beware opinion polls.

A divided country

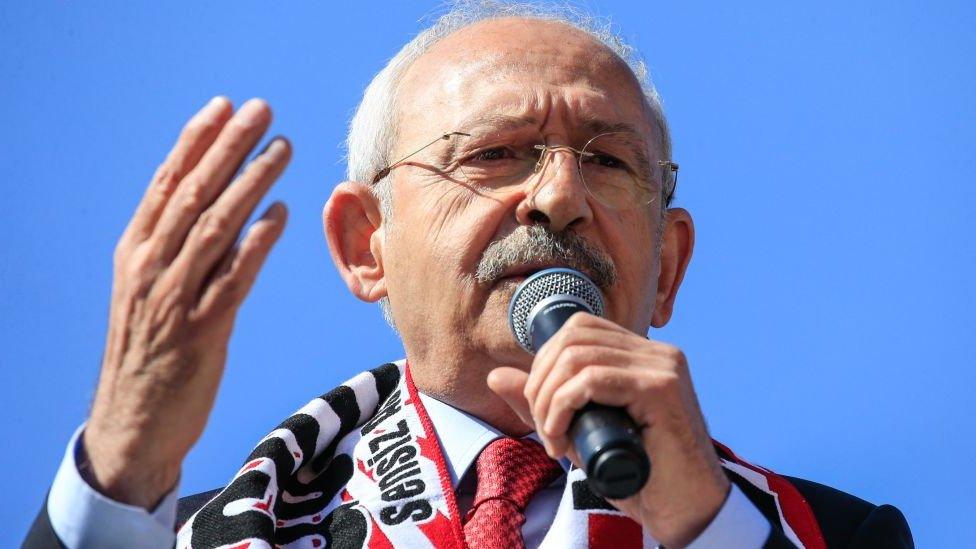

His rival Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the secular opposition leader, got 44.9%. So, the electorate in this polarised country was split - the two sides implacably opposed but just 4% apart.

An ultra-nationalist candidate, Sinan Ogan, took an unexpected 5.2%, pushing the contest to a second round this Sunday. He has now endorsed President Erdogan.

President Erdogan is the favourite to win the second round of the elections

Why have most voters stuck with him despite the economic crisis, and the government's slow response to disastrous twin earthquakes in February, which killed at least 50,000 people?

"I think he is the [ultimate] Teflon politician," says Professor Soli Ozel, who lectures in international relations at Istanbul's Kadir Has University. "He also has the common touch. You can't deny it. He exudes power. That's one thing that Kilicdaroglu does not."

Mr Kilicdaroglu, who is backed by a six-party opposition alliance, used to exude hope, and promise freedom and democracy.

But after his first-round disappointment, he made a sharp right turn. Now there is less of the caring grandfather and more of the nationalist hardliner. "It is a race to the bottom," according to one Turkish journalist.

"I am announcing here that I will send all refugees back home once I am elected President, period," said Mr Kilicdaroglu at a recent election rally.

That includes more than three million Syrians who fled war at home. It is a message that goes down well in Turkey.

Whoever is Turkey's next president, nationalism is already a winner here. The voters have elected the most nationalist and conservative parliament ever, in which Mr Erdogan's ruling AK (Justice and Development) Party coalition has retained control.

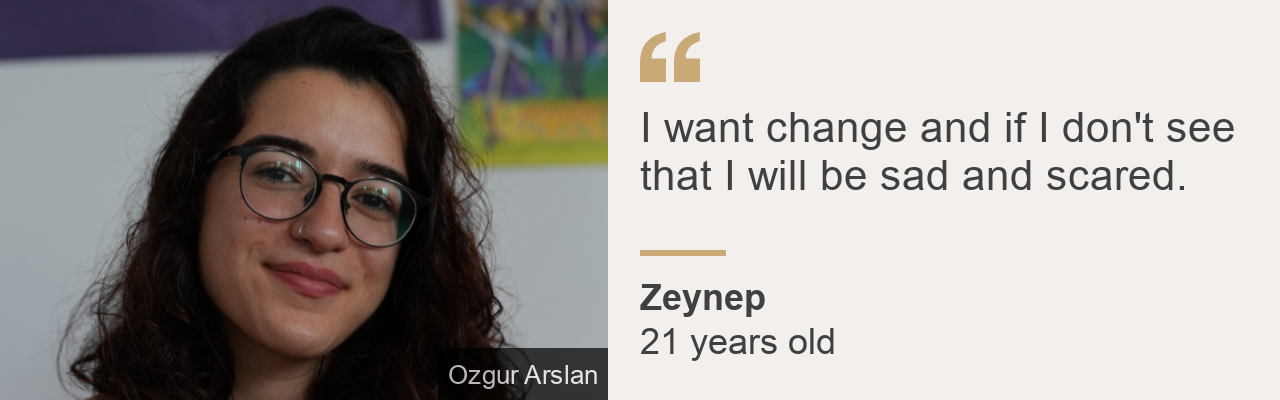

For some young voters it feels like the die has already been cast here. Sitting on a red couch beneath a rainbow flag, Zeynep, 21, and Mert, 23, serve piping hot Turkish tea and worry about the future.

Both study psychology at Bogazici University, a respected seat of learning with a history of now-suppressed student protests. Their friendship began at the university's LGBTQ+ club, which has since been closed. Gay pride parades have been banned starting from 2015.

During the election campaign, the president has been targeting the community. "No LGBT people come out of this nation," he told a packed rally in the city of Izmir. "We do not tarnish our family structure. Stand up straight like a man, our families are like that."

The community is now at growing risk, according to Mert, who has shoulder-length dark hair and earrings.

"Erdogan himself, in every speech, at every event he holds, has started to portray us as targets," he said. "Day by day, the state is making an enemy out of us."

A new Turkish century

"What the government says has an impact on people. You see it reflected in those closest to you, even in your family. If this continues, then what next? We end up always living on alert, always tense, always in fear," he said.

Zeynep - who has dark eyes and expressive hands - is still hoping for a new era but knows it may not come. "I am 21 years old and they have been here for 20 years," she said.

"I want change and if I don't see that I will be sad and scared. They will attack us more; they will take our rights more. They will ban many more things, I think. But we will still do something, we will still fight."

On Sunday, voters will go to the polls for the first presidential runoff in their history with their country at a turning point.

It is almost 100 years since Turkey was founded by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk as a secular republic.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is promising a new "Turkish century" if he is re-elected.

His supporters say he will deliver more development and a stronger Turkey. His critics say it will be less Ataturk, more Islamisation, and a darker future.

- Published23 May 2023

- Published25 May 2023

- Published20 May 2023