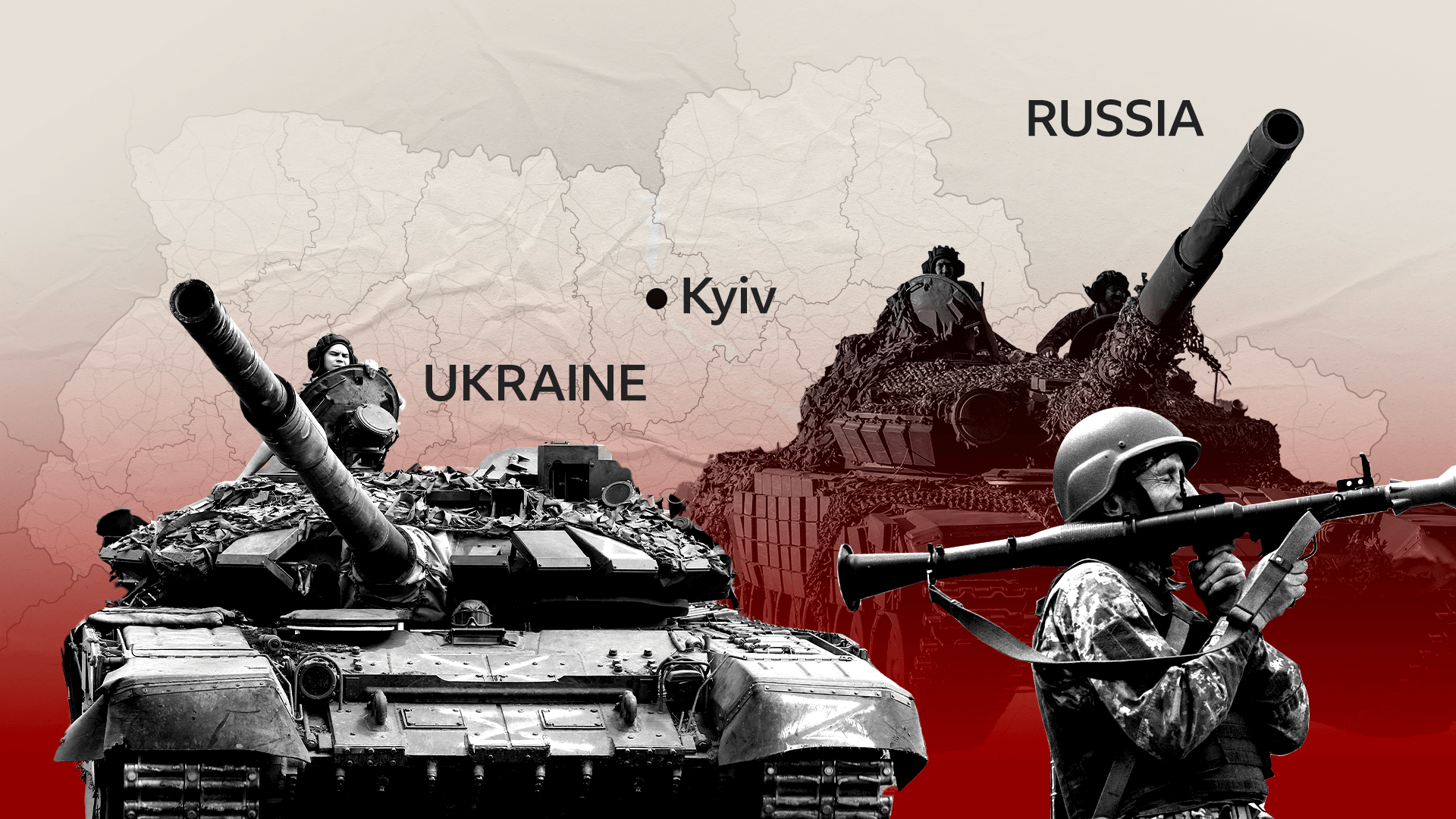

Ukraine war: Russia hits Odesa after killing grain deal

- Published

Russia has repeatedly attacked the Ukrainian port city of Odesa in the days since it withdrew from the grain deal

The Ukraine Grain Deal. 22 July 2022 - 17 July 2023.

A short life, with its flaws, but the only diplomatic light in the darkness of Russia's invasion.

It had allowed Ukraine to export its grain to the world through the Black Sea.

A third less than normal, but still 33 million tonnes. However, in recent months, its health had deteriorated.

Russia was accused of slowing the route with naval blockades and long inspections, and the deal finally succumbed.

Last week saw Moscow's official withdrawal. Russia then launched a wave of missile strikes on ports it once promised to leave alone.

EXPLAINED: What was the Ukraine grain deal?

One site destroyed was a grain terminal owned by one of Ukraine's biggest producers, Kernel. Officials say more than 60,000 tonnes of grain has been destroyed in the past week.

"We stopped our exports for the first two to three months of the war," explains Yevhen Osypov, Kernel's CEO.

"The prices of oil and grain went up by 50%, and you can see the same happening again now."

While global grain supplies seem to be stable for now, global markets saw the price of grain rise by 8% within a day of Russia pulling out - the highest daily rise since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February last year.

Russian President Vladimir Putin now says his country "is capable of replacing the Ukrainian grain both on a commercial and free-of-charge basis, especially as we expect another record harvest this year".

In an article published on the Kremlin's website ahead of this week's Russia-Africa summit, President Putin wrote that "Russia will continue its energetic efforts to provide supplies of grain, food products, fertilisers and other goods to Africa".

Both Russia and Ukraine are among the world's leading grain exporters.

At the weekend Russian missile strikes severely damaged Odesa's Transfiguration Cathedral, in the city's Unesco world heritage-listed historic centre

The Kremlin had earlier agreed not to target port infrastructure in three locations in the region, but that diplomatic shield is no more.

With damaged ports, no agreed corridor through the Black Sea and Russia controlling most of the coastline, Mr Osypov believes Ukraine's grain export capacity will drop by a further 50%.

"It's a huge challenge for our farmers because they'll have to sell their products 20% below cost," says Mr Osypov, who predicts there will be fewer people in the future working less land.

The death of the grain deal extends well beyond Odesa's ports. The city's mayor Gennady Trukhanov thinks Moscow just wants to show nothing will be exported without them, and he's right.

"The most terrible thing is that in order to achieve their goal, they've attacked innocent people," he says.

Ukraine is known as Europe's breadbasket because of the vast amount of grain it produces

You're left in little doubt over the scale of Ukrainian grain production when standing 40 metres high on top of a silo in the central Poltava region.

The plant we're in can hold 120,000 tonnes. It's around a third full, and while Ukraine is unable to export through the Black Sea, it will keep filling up.

The site is surrounded by an endless agricultural expanse.

This is a country which can't suddenly stop producing grain. It has to go somewhere - or at least that's the hope.

"We feel there is a need for us to harvest as much grain as possible," says Yulia, a lab technician at Kernel, as she pours samples into a pipe.

Before the birth of the grain deal, tens of millions of people from some of the world's poorest countries were at risk of starvation because of Ukraine's inability to export it.

Twelve months later, that risk has returned.

"The Russians probably don't understand what hunger is," says Yulia. "People are starving, there's a large supply, but they can't get it for no reason."

Lab technicians like Yulia test Ukraine's grain once it has been harvested

Moscow had threatened to pull out before, mainly saying there were too many restrictions on its own agricultural goods.

It also wants a major bank let into a global payment system, restrictions lifted on Russian fertiliser companies, and for its ships to get full access to insurance and foreign ports.

President Putin has now turned those complaints into demands. However, if they were to be met, that would require a relaxation of western sanctions, which is hard to imagine.

Last July, the Kremlin had seemed keen to be "part of the solution" when it came to the food crisis that it has directly caused by invading Ukraine.

Battlefield frustrations seem to have changed that stance.

Despite the lack of a pulse, Turkey - one of the main brokers of the grain deal along with the United Nations - is still hopeful it can be resuscitated.

The UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres (left) and Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan helped broker the grain deal in 2022

So, assuming the initiative is indeed dead, is there an heir apparent? An alternative solution for Ukraine to export?

Road and rail has been used through neighbouring countries like Romania and Poland, but there have been times when Ukrainian grain has flooded their markets and driven down prices, to the annoyance of farmers.

The River Danube has also been developed as a route through central Europe, with two million tonnes of grain making it through in the last 12 months, compared with 600,000 the year before.

However both scratch the surface of what Ukraine hopes to shift, and are much more expensive logistically.

During her recent visit I asked the head of US Aid, Samantha Power, whether Ukraine's status as "Europe's breadbasket" was a thing of the past.

She'd just announced a package worth almost a billion dollars for Ukraine, which included agricultural modernisation.

"We're doing what we can, but there's no substitute for peace," was her reply.

Additional reporting by Aakriti Thapar, Anastasiia Levchenko and Anna Tsyba

Related topics

- Published2 April 2024

- Published7 July 2023