Aleksandar Vucic: The man who remade Serbia

- Published

Aleksandar Vucic has consolidated his rule by eroding democratic institutions, opposition activists claim

Aleksandar Vucic has dominated Serbian politics for the past decade, first as prime minister and later as president.

To supporters he is a pragmatic leader who overcame Serbia's deep divides and presided over sustained economic growth. Critics complain he consolidated power in his own hands and undermined democratic norms.

He is now more than a year into the second and final five-year presidential term he is allowed to serve.

Last month he called early parliamentary and local elections for next Sunday, amid mass protests at home and international demands to resolve Serbia's longstanding conflict with Kosovo.

The Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) he led for more than 10 years until this year looks set to be returned to power.

But a united opposition aims to make gains, targeting the mayoralty of the capital Belgrade, home to nearly a third of the population.

That kind of victory could irrevocably dent Mr Vucic's authority.

For Zorana Mihajlovic, who has fallen out with him since serving as deputy prime minister, he is "a populist on the way to becoming a dictator".

The watchdog Freedom House today ranks the country he leads as only "partly free".

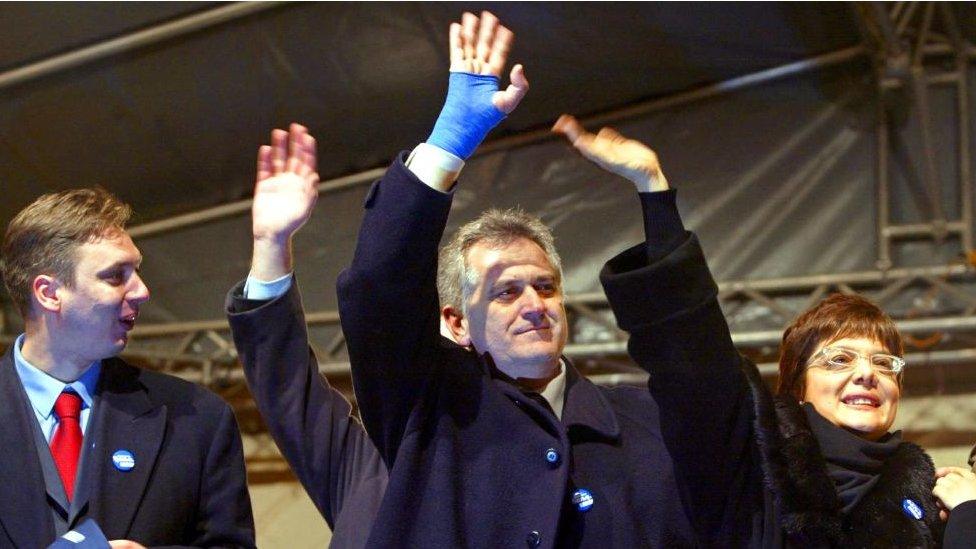

For several years after the fall of Slobodan Milosevic, Aleksandar Vucic (L) and his political colleagues were out of power

Aleksandar Vucic was born in Belgrade in 1970, when Serbia was still a part of Yugoslavia, a socialist federation in the Western Balkans. He recounts how his family left Bosnia after suffering persecution from Croatian fascists during World War Two.

For a time in the 1980s he lived in the UK, where he learned English. With the money he earned working in a hardware store he bought a small radio, which he took home.

"My parents were delighted when they saw it," he later recalled in a speech to the London School of Economics.

It was when Yugoslavia broke up in the early 1990s that the brutal Balkans wars began. Serbia and Montenegro were all that was left in the rump Yugoslavia - along with Kosovo, a breakaway region of Serbia with an ethnic Albanian majority population.

Influenced by Serbian ultra-nationalism and football hooliganism, Mr Vucic joined the far-right Radical Party aged 23. The Radicals sought a Greater Serbia by taking land from neighbouring countries.

"You kill one Serb and we will kill 100 Muslims," he infamously said days after the Srebrenica massacre in July 1995, when 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were murdered by Bosnian Serb forces.

In 1998, Yugoslav strongman Slobodan Milosevic made Mr Vucic his information minister. In government, Mr Vucic was responsible for implementing some of Europe's most restrictive laws on freedom of speech.

It was an era "marked by ethnic cleansing, hatred towards Croats and Muslims, sanctions and wars", says Zorana Mihajlovic.

Ethnic Albanian refugees fleeing Kosovo in 1999

In 1999, Nato forces began bombing Yugoslavia in a bid to bring an end to violence against ethnic Albanians by Yugoslav forces in Kosovo.

Soon Mr Vucic and his colleagues were out of power. In 2008 he and other former members of the Radicals founded the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS).

He underwent a public change of heart, renouncing his previous ultra-nationalism and pledging to take Serbia into the European Union. That year, Kosovo declared independence, a move never recognised by Serbia.

Mr Vucic's progress up the ranks of Serbian politics was swift:

In 2012, the SNS won parliamentary elections, going into coalition with the Socialist party

Mr Vucic was appointed deputy prime minister, then prime minister in 2014

In 2017, he was elected president with a majority in the first round of voting.

Having risen to the top, Mr Vucic consolidated his rule.

Opponents say he did so by eroding democratic institutions in a manner reminiscent of the authoritarianism of the 1990s. Ms Mihajlovic believes Serbia "has been distancing itself from the EU and democracy".

"The government is in nearly complete control of all levels of public institutions and the media," says Florian Bieber, an expert on Serbian nationalism at the University of Graz.

Vucic supporters reject that characterisation, seeing his domination of Serbian politics as down to successful governance.

They point to the Vucic era as one of unprecedented growth, of a post-communist country overshadowed by war becoming an advanced, European economy.

Marko Cadez, head of the Serbian Chamber of Commerce, credits his economic policies with doubling Serbia's GDP over the past decade.

"Aleksandar Vucic knows the art of politics," he says. "He conducted reforms that weren't easy or pleasant."

Mr Vucic also argues he should be given credit for managing stable relations with Kosovo.

In September, a flare-up of violence in majority-Serb northern Kosovo left four people dead, reviving fears of regional instability.

But the Serbian leader has recently signalled he is willing to formally normalise relations with Kosovo. That has led political opponents to accuse him of treason.

Mr Vucic has cultivated good relations with rival geopolitical powers.

He says he wants Serbia to join the EU, which accounts for over half of Serbia's trade. But at the same time he has championed friendly relations with Russia and opened Serbia up to Chinese investment.

Mr Vucic has welcomed Chinese investment in Serbia

In October, he signed a free-trade deal with China after a decade of increasingly close economic ties.

Chinese companies have been chosen to build roads and railways in Serbia, making the Balkan country one of the focal points of President Xi Jinping's Belt and Road Initiative in Europe. A Chinese company already runs a large copper and gold mine in eastern Serbia.

"For Serbia, co-operating with all global actors is a very good thing," says Katarina Zakic, head of the Belt and Road Regional Centre at Belgrade's Institute of International Politics and Economics.

Shortly before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, Mr Vucic infamously said he would not oppose Kremlin policies, as "85% of Serbians will always side with Russia whatever happens".

It was an exaggeration, but he kept his word. Serbia has refused to back EU sanctions against Moscow, despite holding EU candidate status. Russia has consistently backed Serbia by voting against international recognition of Kosovo.

His government has even been accused of facilitating the re-export of sanctioned "dual-use" technology to Russia.

Protests sparked by two mass shootings were some of the largest in recent history

Zorana Mihajlovic believes he is not instinctively pro-Russia, but purely pragmatic: "The more isolated Serbia is, the stronger his grip on power."

His biggest test in 17 December elections will come from Belgrade, after opposition parties harnessed anger over two mass shootings last May in which 19 people were killed. One was at a Belgrade primary school.

A coalition called Serbia Against Violence (SPN) is riding high in the polls and hopes to win control of the capital.

But Mr Vucic is confident of victory and accuses his rivals of being fixated on removing him from power. "We will see who will be laughing after the elections."

Related topics

- Published3 April 2022

- Published2 October 2023

- Published11 September 2023