Orpheopolis: France's unique orphanage for police children

- Published

Orpheopolis has cared for the children of police for more than a century

Squeezed between a hospital and a busy dual carriageway heading to France's Mediterranean coast is a discreet, sprawling walled compound that serves as a remarkable haven.

This is an orphanage that has a unique role - and one of a network of three, called Orpheopolis.

All the orphans have lost a mother or father who were serving police officers. Some have lost both.

Around 70 children are housed in each one of the three orphanages. But in total, Orpheopolis provides care for some 1,000 orphaned children. Many are living with a surviving parent or relatives, but still need constant psychological care or financial support.

Their parents have died from numerous different causes: illness, gun and bomb attacks, accidents related to their work, and often from taking their own lives following depression or post-traumatic stress. Between 50 and 70 officers die by suicide each year in France.

Some 20 children aged 10-18 live in one of the orphanages on the outskirts of the town of Agde.

Despite their tragic personal situations, it's vital that they are integrated into wider society

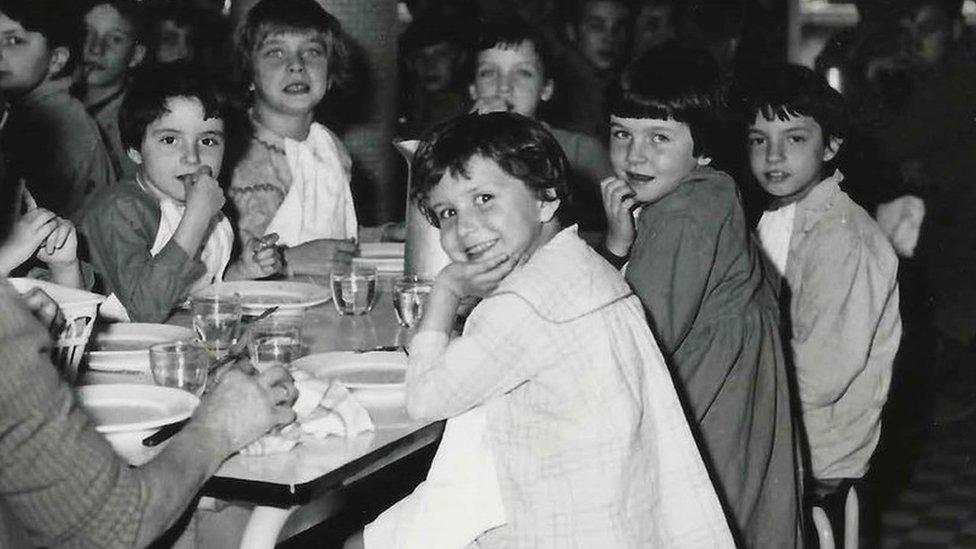

"Despite their tragic personal situations, it's vital that they are integrated into wider society, and that's why they go to local schools and have lunch in the canteens like everyone else," director Christophe Bart told the BBC.

"They can even invite friends back to the centre. It's crucial to break their social isolation."

One boy called Alexandre was celebrating his birthday while the BBC was there and nine of his friends from school had been invited over. Boyfriends and girlfriends are allowed to visit, although none are allowed to stay overnight.

What is remarkable about the orphanage is the safety net it provides.

The equivalent of 28 full-time staff look after 20 children, including round-the-clock social workers, psychologists, housekeepers, sport coaches and after-school support teachers.

They live in four separate housing blocks where they cook, eat and socialise together. Upstairs they have individual bedrooms.

The children cook, eat and socialise together

There are common play areas, a garden, and a well equipped outdoor sports facility. There are strict house rules on bedtime and mobile phone use that wouldn't be out of place at a British boarding school.

"For sure what unites these children is mourning, and an overwhelming feeling of sadness. So we work on that - it's about dialogue," says 30-year-old social worker Louis Rodriguez.

"A strength for these kids who are missing one or both parents is that they can speak amongst themselves, as they are all in similar situations and facing common experiences."

What unites these children is mourning, and an overwhelming feeling of sadness

For three days the BBC was able to speak to the children, first in Agde and then at another centre in Bourges in central France.

Seventeen-year-old Elena has been at the orphanage for four years. Her father was one of the first police officers to arrive on the scene of the attack on Paris's Bataclan concert hall in November 2015.

Some 130 people were killed in simultaneous gun and bomb attacks across the city that night, including 90 at the concert venue.

Elena says she does not know if her father took his own life later because of the harrowing experience he witnessed that night, but the orphanage has allowed her to heal too.

Elena's father was one of the first officers at the scene of the Bataclan attacks in 2015. He later died by suicide

"After my father's death it was very difficult for my mother and myself. I couldn't stay at home and coming here provided me with some stability," she says.

"I would be a lot angrier today if I didn't have all this support structure around me. Now I can move on, I will soon leave to start a career as a social worker."

Rage is a word that surfaces a lot to describe the children when they first arrive.

Ambre, 12, is sports crazy and training with the local football team whenever she can. When her father died of cancer she had no other relatives to turn to and she has been here four years now.

"I was very angry when I arrived," she remembers. "It was very difficult for me. But I am a lot calmer now and I consider here as my second home."

Some of the orphans are siblings and go home to a parent or relatives at weekends, but not all of them have that family support to depend on. Some of the kids I spoke to were clearly emotionally scarred by their experiences.

Psychologist Laure Lamic has spent the past eight years working with the children in Agde, and says she is able to offer the children the chance to speak "in a confidential, trusting and free manner [where] there is no censorship".

The orphanages have a combined annual budget of €15m, providing the children round-the-clock support

"This is important because they have suffered a loss and while it's difficult for everyone to talk about death it's even more so for children.

"But we help create a healing process and you can see it in their school reports and with an improvement in their emotional state."

Orpheopolis has an annual budget of €15m ($16.3m; £12.9m) which includes running the three orphanages. Most of that comes from donations, and 38,000 police officers contribute to a fund each year.

The organisation has been going for more than 100 years.

The first orphanage was created after two officers were killed, leaving children behind with no family to support them. Agde's mayor, a former police officer, provided the land for free.

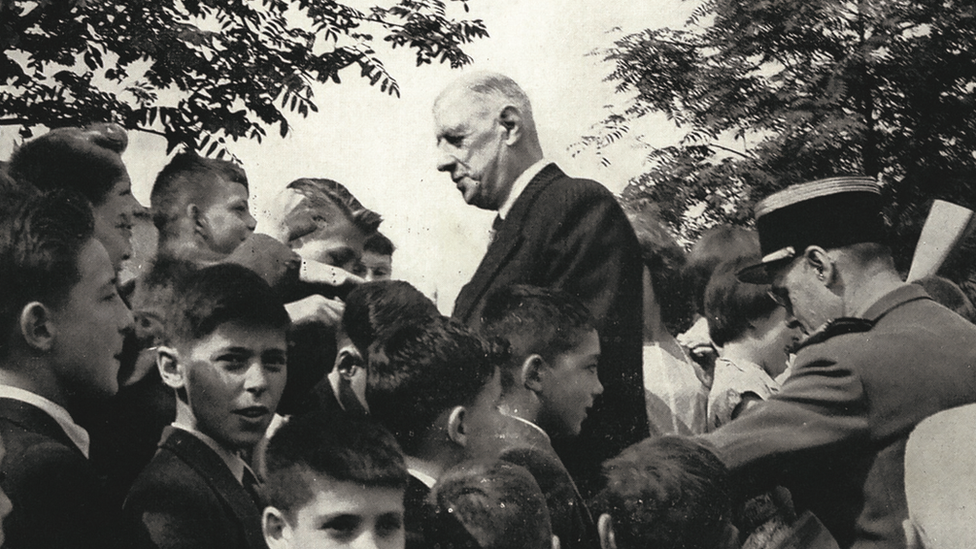

To this day, high ranking police officers sit on the board and visit regularly along with senior politicians.

Charles De Gaulle was one of many senior politicians to visit Orpheopolis

Some of the children blame the police for their parents' deaths, and have a seething resentment of the force. But others want to follow in their footsteps - despite the obvious dangers that go with the job.

The centre in Le Bourges specifically prepares those children who want to join the police, with work towards the entrance exam, rigorous sport activity and hands-on experience at the nearby police headquarters.

For Alexandre Revello, who's 18, joining the police came as a natural step. His father was a police officer involved in mountain search and rescue operations and slipped and fell to his death in a tragic accident.

"It's not to honour my father's name or anything like that. It's about protecting people and reassuring them."

Alexandre Revello is now training to join the police, like his father

Every year around 150 young people are considered physically and psychologically strong enough to leave Orpheopolis and get on with their lives.

The Police Federation of England and Wales, which represents nearly 150,000 officers, told the BBC while there are charities to support officers' families there is nothing comparable to what exists in France.

Orphanages used to exist for the children of UK police officers, but they closed down in the late 1940s and early '50s.

It is extremely rare for journalists to be allowed into the French orphanages and the first time foreign reporters have been invited in.

The network said it wanted to highlight a programme that worked and that might serve as a model elsewhere.

Additional reporting by Paul Pradier

Related topics

- Published6 March 2024

- Published29 February 2024

- Published16 February 2024