Frank Falla: The journalist who lobbied for the Nazis' victims

- Published

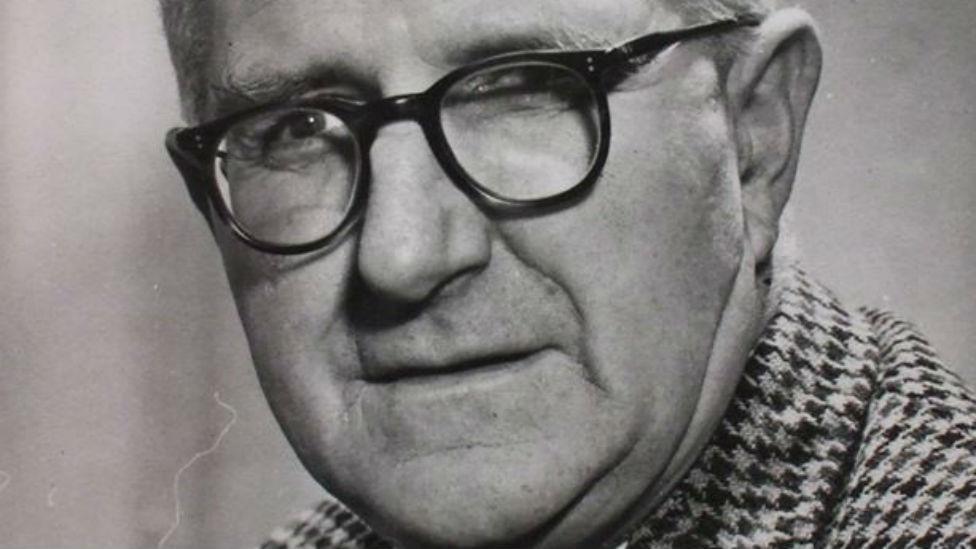

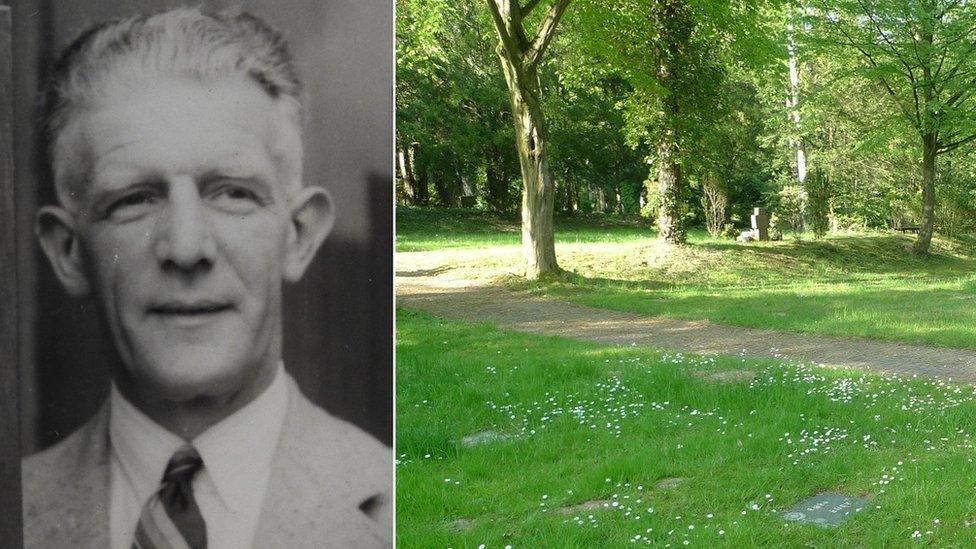

Frank Falla was imprisoned for his role in covertly spreading BBC news

Locked in a Nazi prison and suffering from pneumonia, in February 1945 journalist Frank Falla made a promise to himself: he would muster all his remaining strength to try to survive the sickness, beatings and starvation, hoping the advancing Allies would come to his rescue before it was too late.

Only his survival, he believed, would guarantee that the families of six of his fellow Channel Islanders would know how their husbands, fathers, and sons had died.

The "gentle" journalist, whose life story is told as part of a new exhibition at London's Wiener Library,, external found himself in the brutal Naumburg prison for covertly sharing BBC news in his native Channel Island of Guernsey - British soil, occupied by Nazi Germany for five years.

Witnessing prisoners dying at a rate of 10 a week, Falla would cling on, surviving the bout of pneumonia to be liberated two months later by US forces, when a doctor told him he was just days from death.

He was lucky.

Thirty islanders deported to Nazi prisons and concentration camps died along with millions of others during World War Two.

But surviving the war was only the beginning of Falla's struggle for their suffering to be recognised.

A German band marches through St Peter Port High Street, Guernsey. The island was occupied between June 1940 and May 1945

After the war, it was Falla who helped the widow of fellow Naumburg prisoner Joseph Gillingham.

Like Falla, Gillingham had been imprisoned for his role in covertly spreading BBC news to the people of Guernsey, whose radios had been confiscated by the Germans.

He was seen by Falla and another prisoner leaving Naumburg on completion of his sentence, but how he died remained a mystery until 2016.

As a single mother Henrietta Gillingham struggled financially after the war, taking odd jobs to cover her "inadequate" widow's pension. That changed after Falla knocked on her door in 1964.

"I can recall him coming to our house," her daughter Jean, then 21, recalls.

Falla helped her mother and uncle, also imprisoned at Naumburg, to put together a compensation claim that would eventually yield £2,293, equating to £42,642 today, which Jean says made their lives far more comfortable.

"They were living in rented premises, and a year or so later, after the compensation had come through, the house went up for auction and between the two of them they bought the house with their compensation money.

"It's something they never could have done in previous years," Jean says.

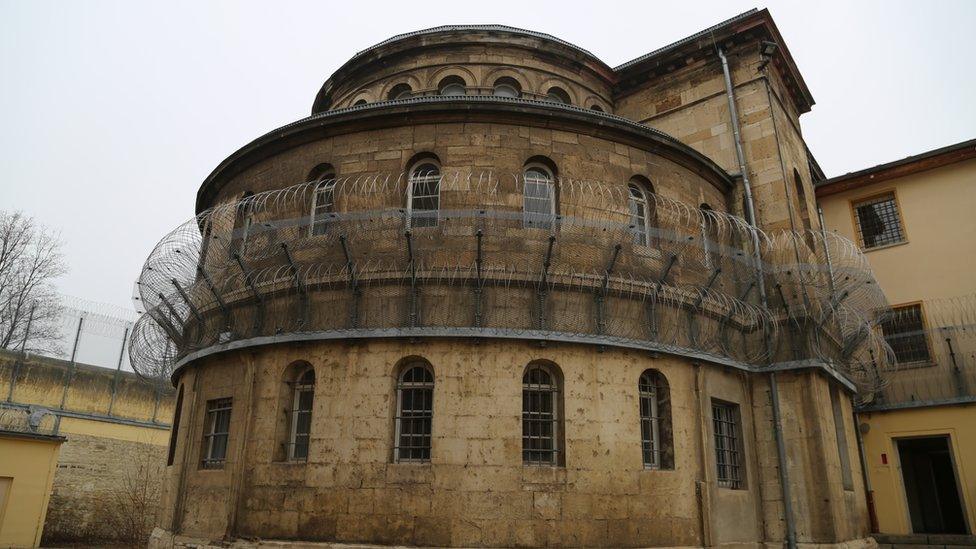

Naumburg prison is no longer in use but inside little has changed since 1944 when it housed 350 inmates

Falla would become a spokesman for families like the Gillinghams, lobbying on their behalf and using his skills as a journalist to help them write testimonies of wartime imprisonment to be submitted to the British government.

During the war he had used the same skills in a battle of wits against German censorship of Guernsey newspapers. In the end, it was the sharing of BBC News, transcribed from radio broadcasts listened to on banned radios, that would lead to Falla's prison sentence of one year and four months in April 1944.

Twenty years later, it was confirmed Channel Islanders would be eligible to claim from a £1m West German fund for British victims of Nazi persecution and ill-treatment, although the idea of compensation for British people had first been mooted in 1957.

Falla's early hopes of islanders' inclusion quickly turned to disillusionment when, as he later reflected, he found a lack of desire among both Guernsey's politicians and imprisoned people to claim, saying islanders were "too proud" to accept German "charity".

Frank Falla (furthest right) organised annual dinners for survivors of German prisons and concentration camps, where the Queen and "absent friends" were toasted

But as the years passed, the mood changed.

Falla found an ally in the form of Conservative MP and former prisoner-of-war Airey Neave, whom he described as his "knight in shining armour".

Lobbying by the MP - who in 1979 would be murdered by Irish republicans, external - helped to ensure the 1964 agreement included people from the Channel Islands.

By now a freelance journalist, Falla got to work writing articles in local newspapers letting people know they would be eligible to claim.

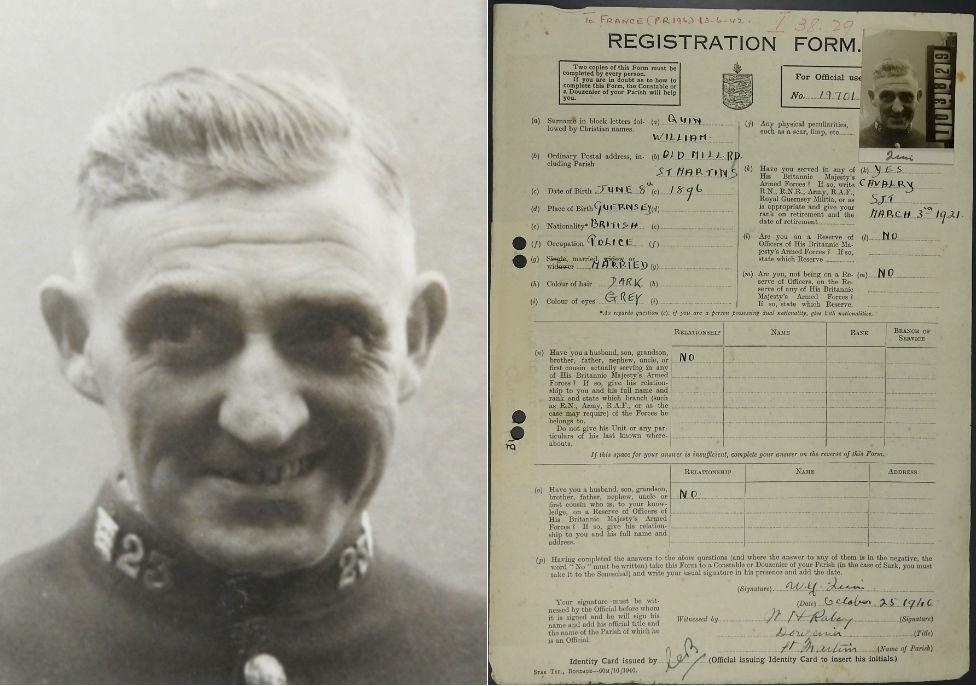

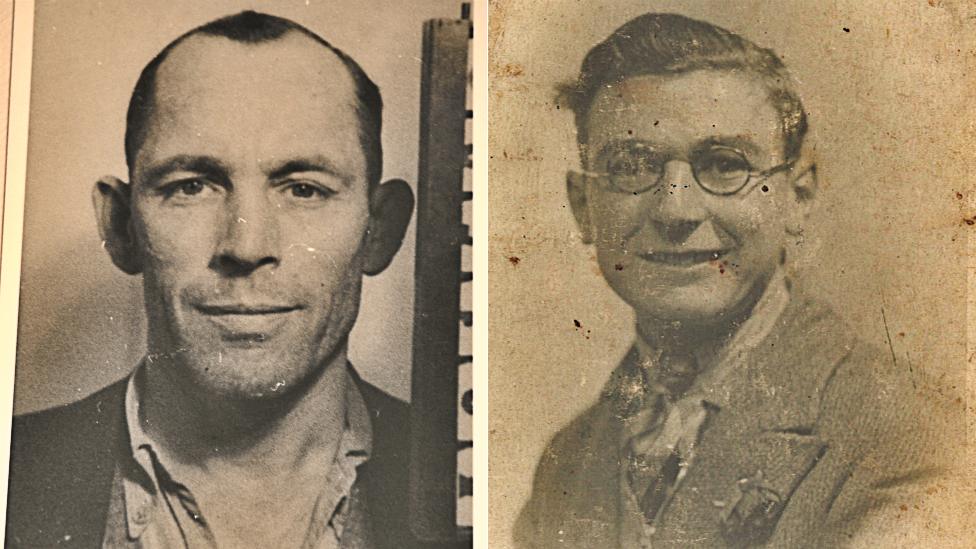

Policeman William Quin was controversially deported for his role in stealing from food supplies during shortages

William Quin, a World War One veteran and policeman was one of them.

Falla believed trauma from his time in captivity accounted for a lack of detail in his initial claim, which was turned down.

He suffered a torrid time in captivity, Falla wrote, being starved, beaten and eventually force-marched as the Allies advanced at the end of the war.

In 1966 an appeal to the Foreign Office by the journalist suggested the case had been "grossly understated".

"In the working party he was picked out and victimised by the Wachtmeister because he was an Englishman, but towards the end this eased. Before this when the Germans thought he was not working hard enough, they used to lay into him with shovels they were all using - and this with little mercy shown."

The appeal was successful, and Quin received £3,303, which equates to £61,425 today.

Typical daily rations at Naumburg prison would consist of a six ounces of bread and a litre of soup

The stories of Falla and his fellow prisoners are documented in the new Frank Falla Archive, external, a tribute to the man who swapped a prison ration of bread for a stub of pencil to record the names of Channel Islanders as they died.

The archive, put together by a team of researchers led by Cambridge historian Dr Gilly Carr, is based largely around those testimonies, some written by Falla on others' behalf.

"He's a hero to me," she says.

"I think that he is amazing for having done the work he did at a time when men like him, who were deported for acts of resistance were seen as criminals, were seen as stupid: those were the words that were used because they risked bringing reprisals against others from the Germans.

"I think Frank and his friends who, like him, stood up to Nazism never lost sight that standing up to far-right politics can only ever be a good thing."

In his account of his life under the Nazis, The Silent War, Falla details both resistance and collaboration, including the Irish man who informed on him and others, leading to their imprisonment and, for Joseph Gillingham and another member, death.

'We ate the flesh and blood of our fellow prisoners'

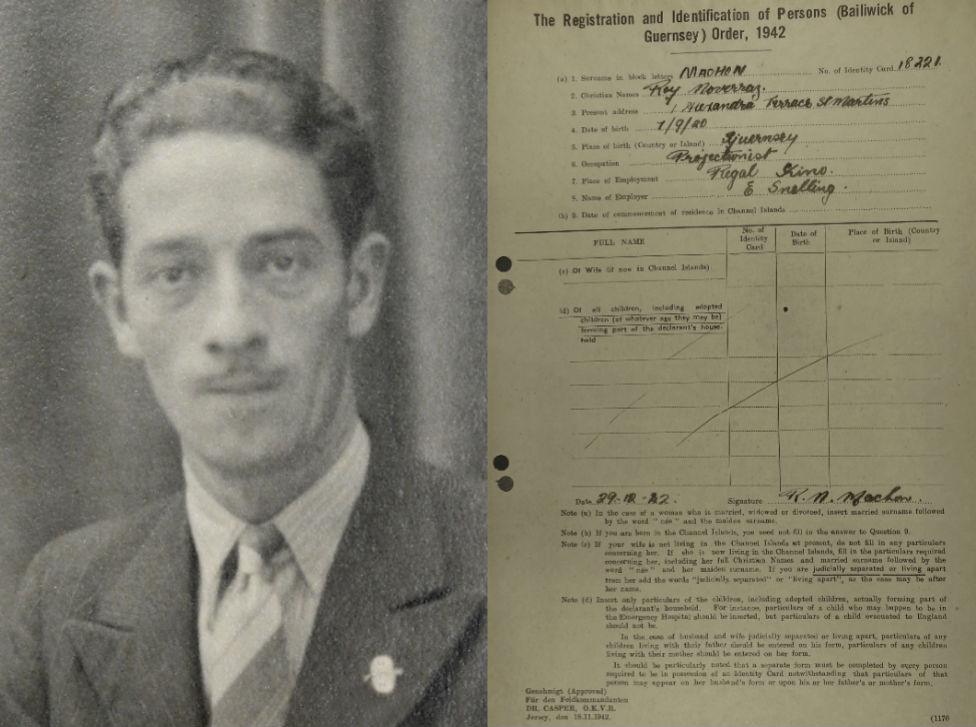

Roy Machon, a 22-year-old cinema projectionist, was another prisoner whose case Falla took up with the UK Foreign Office.

After serving time in Guernsey prison he was deported in 1943 to a civilian internment camp in southern Germany, but a further infringement led to him being sentenced to five months' hard labour at a Munich prison, where he became permanently deaf after being severely beaten.

Roy Machon was imprisoned for making V-sign badges, worn by islanders as a symbol of resistance against their Nazi occupiers

In his compensation testimony, Machon said many of his fellow workers suspected they were being fed the flesh of dead workers.

"On Wednesdays and Fridays we were given a small piece of blood sausage or a small piece of meat in our soup. It was commonly known and spoken about by prisoners, that we were eating the flesh and blood of fellow prisoners who had been killed by the Nazis."

Falla intervened but despite Machon's deafness and the appalling conditions he had endured, his claim was turned down.

Under UK Foreign Office rules, compensation was typically given for being interned in a "concentration camp or comparable institution", meaning many British people, including those who were held in civilian internment camps, were not eligible.

Many were from the Channel Islands, forcibly deported to southern Germany, but owing to relatively better conditions Falla was not able to help those who felt aggrieved at their loss of freedom.

It is difficult to estimate how many islanders he assisted, but Dr Carr says one figure stands out above all - that of the 100 who applied over half were successful in their claims.

That was much higher than the average success rate of British claims - only a quarter of the 4,015 applicants were successful., external

Although Falla did not assist with all applications, his knowledge of the rules and skills as a journalist had a significant effect on the success of claims, Dr Carr says.

Some Channel Island prisoners were shackled and packed in windowless cattle trucks with other sick and starving prisoners

She also believes imprisonment took a psychological toll on many islanders after the war, and Falla was no exception.

In The Silent War he recalls suffering "severe night sweats" and hallucinations.

The nightmares of his Naumburg prison cell would eventually stop but, as the archive documents show, Falla's struggles on behalf of islanders continued, something Dr Carr feels should get wider recognition.

Falla's experiences were largely unknown to his son Tim, knew little of his father's efforts until after his death aged 71 in 1983.

He remembers him simply as a "very good person".

"He was a true example of a gentleman, with the emphasis on the gentle.

"The fact that he did what he did after all that is evidence enough of the type of person he must have been."

On British Soil: Victims of Nazi Persecution in the Channel Islands, which includes a section on Frank Falla, is on display at London's Wiener Library until 9 February.

- Published20 October 2017

- Published2 January 2017

- Published20 November 2016

- Published6 May 2016

- Published28 January 2017

- Published8 May 2015