Sumatran orangutans: Meeting the refugees of the lost rainforest

- Published

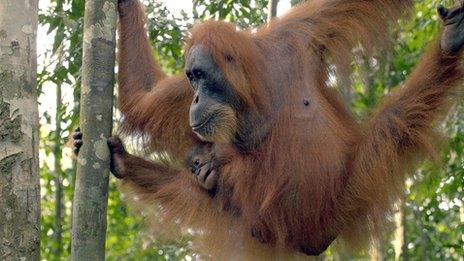

Dana gave birth to a baby girl on 9 June 2013

Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust was set up by Gerald Durrell with the aim of saving species worldwide. Harriet Bradshaw has been looking at the work they are doing with one particular species - the Sumatran Orangutan.

In the early hours of a morning in June my phone rings. The high pitch shrill wakes me up. I have been waiting for this call. The crackly voice on the speaker sounds strained.

"Harriet? It's Rick. I've got news about Dana…"

I'm only six months older than Dana. When I look into her eyes she stares back with intelligence. We are alike. We share 97% the same DNA and we are both female.

Neil MacLachlan, a consultant from Jersey's General Hospital, tells me her anatomy is so similar to mine it is relatively straight forward for surgeons such as him to operate on her.

But, for all the similarities, Dana and I are very different. From the small things like her two missing fingers that were bitten off in a fight, to the dramatic tragedy she faced four years ago when she was bleeding to death after giving birth to a stillborn.

Second chance

It is estimated there are fewer than 7,000 of her kind left in the wild, compared with more than seven billion human beings sharing the same planet. This is because Dana is a Sumatran Orangutan, a Great Ape on the brink of extinction.

She lives in captivity in Jersey as part of a reserve population at the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust.

After Dana gave birth to a stillborn in 2009, she was thought to be infertile. But medical intervention gave her another chance when Neil MacLachlan, consultant gynaecologist from Jersey's General Hospital, performed reproductive surgery on her. Soon she became pregnant.

I travelled to Sumatra in early May to trace Dana's roots and make a documentary about efforts to save her species.

While her pregnant tummy was growing bigger, and she was being trained to present it for ultra-sound scans, I was getting vaccinated ready to travel to where her wild relatives live.

Dr Ian Singleton runs Sumatra's only rehabilitation programme for orangutans who he calls "refugees of the lost rainforest" because he says their forest homeland is being cleared and developed.

Environmentalist Graham Usher says they we will be running drones routinely by the end of 2013

He took us to the overcrowded cages of orangutans at his quarantine centre on the outskirts of the city of Medan. Their cries for attention, so similar to a human child, still haunt me.

'Vicious humans'

Orangutans are protected in Indonesian law, but about 30 enter the care of Dr Singleton's Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme each year.

He said: "There was one Orangutan - Matahari her name was - she had been beaten unconscious, they put a chain around her neck and she was almost dead. Her whole body was swollen, fingers missing, chopped off.

"We brought her to the quarantine and kept her alive for three weeks before she finally packed in. That was horrible. And what really struck me about that case was just how vicious human beings can be."

Dr Singleton said there was research to show that since 1985 about half of Sumatra's rainforest had gone due large scale industries developing it, particularly for palm oil.

The oil is extracted from the fruit of palm trees and used in products from biscuits to shampoo. On the road through Sumatra you can see rows and rows of this mono-crop.

"You sometimes forget you are working with an orangutan they are so similar", said Neil MacLachlan

Indonesia is the world's largest exporter of the oil with estimates of more than 30 million tonnes being sent abroad.

The Indonesian Palm Oil Association says the industry helps alleviate poverty by providing jobs, it is a top contributor to the country's economy and its members are committed to protecting the environment.

Dr Singleton said: "The biggest threat to most species right now is not hunting and collection, it's loss of entire eco-systems and by destroying them you lose your water sources, your climate regulation and a host of other resources."

Seeing the orangutans in Sumatra puts into context the captive ones in Jersey. Gerald Durrell set up his zoo as a safety net for species such as them, should their wild relatives go extinct.

But on the 50th Anniversary of him turning his vision into a charity, has his philosophy of saving species from extinction succeeded?

Dana's keeper, Gordon Hunt, accompanied me to Sumatra. He said: "If Sumatran orangutans do go extinct in the wild then captive populations like these ones in Jersey at Durrell could well be like museum relics of the species.

There are only about 7,000 Sumatran Orangutan left in the wild

"That would be incredibly sad, that all we have left is orangutans left living in zoos. If that is what is left of the Sumatran orangutan then I think as human beings we have failed."

Arriving back in Jersey I get ready for bed one evening. My phone is set to loud so I did not miss news of Dana's pregnancy.

Staff have been waiting eight and a half months for the birth, and in early June I finally have news.

At quarter to midnight on 9 June 2013 a female orangutan came into the world, and the birth was caught on camera - thought to be a world first.

This baby is a small but significant symbol of hope for a species on the edge of extinction.

Watch as Orangutan Dana cleans her new born baby girl moments after giving birth

- Published6 July 2013

- Published10 June 2013

- Published10 June 2013

- Published3 April 2013