Clogged roads and ports harm Brazil's development plans

- Published

Most of the port terminal buildings are dusted by sugar

There is sugar everywhere at one of the terminals in Santos, Brazil's biggest port.

It drips from the high conveyor belts that carry loads from the warehouses to the ships, making piles that resemble week-old snow.

The ground is coated with a dark syrup while the air is full of the sweet and slightly sickly smell of a bakery in the morning.

The rhythm of work is frantic with ships being loaded 24 hours a day amid record exports of sugar.

The long queues of vessels waiting off the coast of Santos for a berth in Brazil's biggest port are a visible sign of the country's booming economy but also highlight the strains economic growth has placed on its infrastructure.

"This is a country that exported $100bn (£63bn) in 2005 and $200bn in 2008. We need very quick and large investment in infrastructure," says Weber Bahal from Brazil's development ministry.

Under President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, investing in infrastructure has been at the heart of what is known as the growth acceleration programme (PAC) launched in 2007. A further $500bn is earmarked for investment over the next five years, says Mr Behal.

Lula has described his preferred successor, Dilma Rousseff, as the "mother of the PAC". She is well ahead of her main rival, Jose Serra, in the 3 October presidential election, according to opinion polls.

But while Brazil's booming economy has led to an overall feelgood factor, investors are concerned about the state of the country's infrastructure, which can add significantly to the cost of getting goods to market.

The port of Santos has made some improvements in recent years - a number of terminals have been privatised and more streamlined operations have been put in place, but it has not been enough to cope with increased demand.

"According to our projections we will almost triple our cargo handling in the next 15 years," says Renato Ferreira Barco, the planning director of Codesp, the state company that manages the port.

"We are dredging the port and creating more berths for bigger ships but the access to the port remains our main bottleneck. We need to reinforce the use of railways and to build new roads in the Santos area."

Exhausted drivers

Access to many of the port's warehouses are down cobbled roads, more suitable for the era of horse and cart than heavy lorries.

Trucker Eloi dos Santos on his concerns about the port of Santos and the roads leading to it

When trucker Eloi dos Santos arrives with his load of coffee he never knows how long he will have to wait. "There are no containers available to store the cargo so we have to wait here. It can take hours or days," he says.

After 35 years on the road, Mr Dos Santos has seen firsthand many of the infrastructure problems that are constraining Brazil's growth.

"There are many roads in very bad shape and this delays our travels and increases the cost to maintain the trucks," he says.

The final stretch of highway that winds for about 80km down through the mountains from Sao Paulo to Santos is in reasonable shape but traffic has been increasing rapidly - 20% up on last year. Accidents caused by exhausted drivers or heavy traffic often create long jams and severe delays.

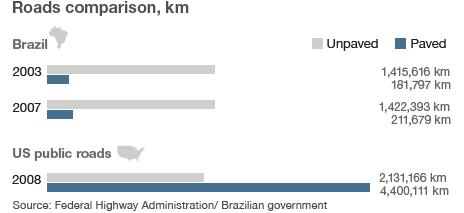

About 85% of the goods that reach Santos come by road. This imbalance in transport dates from the 1950s when Brazil began to favour road haulage over rail freight.

There are projects to develop a better transport mix, including new railways and waterways.

Cosan, one of the world's biggest sugar producers, has its own rail line running into Santos. it has bought new train wagons that can unload sugar in three minutes against the 40 minutes of older models, but more private investment is urgently needed.

"Everything in infrastructure is important but I think that in transport and logistics we have to put a lot of money quickly because in the past Brazil has not invested nearly enough," says Paulo Godoy, president of the Brazilian Association of Infrastructure and Heavy Industries, ABDIB.

"Brazil has money to invest in infrastructure from the National Development Bank (BNDES) but to get the necessary resources we need to create new funds to attract international investors committed to long-term investment."

Airports, airports, airports

The challenge is not only moving goods but also people around the country. Air travel has been growing at a rate of 10% a year and an upgrade in the country's main airports is long overdue.

When asked about what Brazil would have to do prepare its infrastructure for the 2014 World Cup, the president of the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF), Ricardo Teixeira, summarised the biggest problems as "airports, airports and airports".

Brazil is seeing an increased demand for air transport

The two terminals of Sao Paulo's international airport were designed to handle 17 million passengers a year but this reached 21 million last year. Construction of a third terminal has been described as as a priority since the late 1990s.

"The government has announced new plans but that's just what they are for now," says aeronautical engineer and infrastructure expert Jorge Leal.

"We need to find ways to allow private companies to invest in airports in Brazil. I hope that the next government will be more flexible about this," he says.

The bulk of Brazilian infrastructure, the main roads and ports, as well as the telecommunications network, was built in the 1960s and early 1970s, when the military government embarked on a major programme of state investment.

The challenge faced by the Lula government and one confronting whoever is elected on 3 October will be to bring this ageing infrastructure back into shape to ensure Brazil's expectations of growth do not falter.