'Coup' drama plunges Ecuador into uncertainty

- Published

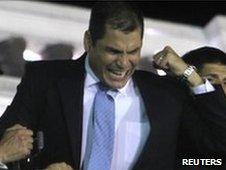

President Correa maintains some popular support despite a series of controversial policies

As dramatic scenes of Ecuador's President Rafael Correa being tear-gassed by his own police force made headlines all over the world, parallels were immediately drawn with last year's upheaval in Honduras, where the military ousted then-President Manuel Zelaya.

This was supported by Mr Correa's own declarations, after he was rescued from a police hospital where he was trapped for 12 hours.

"This was an attempted coup, an attempt to destabilise the government, which failed thanks to the Ecuadorean people," he said from his presidential palace, in front of a jubilant crowd.

It is true that Latin America's new left-wing wave has attracted many foes - in 2002 there was a coup attempt against Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, an ally of Mr Correa. But talking about a traditional coup in Ecuador, or even a coup at all, might be going too far.

The protests started on Thursday morning, as police and soldiers staged a mutiny against some aspects of a new civil service law.

The lower ranks of both institutions rebelled, while the high commands came out to support the government - indicating there was no mastermind, but rather a spontaneous popular uprising.

Correa's leadership style is seen by many as confrontational

According to the protesters, the new law reduces benefits by increasing the amount of time necessary for a promotion, and eliminating the monetary compensation that comes with those promotions.

On Wednesday night, Mr Correa used a veto to change the law, which had been approved a couple of weeks earlier by Ecuador's legislature, the national assembly.

Government ministers argue that the new policy will not harm officers' benefit packages, and that during Mr Correa's term salaries for policemen have increased notably, from $700 (£440) a month to $1,200 - more than twice the average wage. But the strike went on regardless and the country quickly descended into chaos.

Constitutional changes

Mr Correa was first elected in 2006 with a large popular mandate and a left-wing agenda, and set up a constituent assembly.

The new constitution, approved in a referendum in 2008, gave the assembly a few months to draft a new legal framework for the country. The initial deadline for some of the most crucial and controversial laws was mid-October 2009.

This deadline was repeatedly pushed back because of protests and the lack of a clear majority within the assembly - even members of Mr Correa's Alianza Pais are often not aligned with the president on some crucial votes.

Moreover, the government has a budget deficit of at least $4bn (£2.5bn) this year, and it also lacks a choice of lenders it can secure loans from.

After defaulting on $3.2bn in global bonds last year, Ecuador cut itself off from capital markets and multilateral lenders such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Earlier this week Mr Correa was, according to the local press, considering the possibility of dissolving the assembly and ruling by decree until new elections because of the deadlock.

This move would have to be approved by the Constitutional Court first, and this seems more likely after Thursday's events.

Over the past year, environmentalists, students, teachers, journalists and miners have protested against Mr Correa's policies.

Even indigenous people, which make up a quarter of Ecuador's population and were initially in favour of Mr Correa, went to the streets against new laws regulating mining and water management.

On Thursday, Lourdes Tiban, an opposition politician with the Pachakutik indigenous party, condemned the police violence, but said Mr Correa was responsible for it.

"This is the result of months of protests all of the social sectors that have been trampled on by the government," Ms Tiban told BBC News.

"Correa can't act as a victim right now and say there's been a coup attempt. There's been no coup attempt whatsoever. What's happening now is his responsibility, he's calling for a confrontation."

Leadership style

Mr Correa's style is often described as confrontational.

On Thursday, after police occupied their barracks nationwide, leaving the country in chaos, Mr Correa personally visited Quito's main barracks.

He tore at his shirt while he said: "If you want to kill the president, here he is. Kill him, if you want to. Kill him if you are brave enough."

Soon afterwards, he was forced to flee wearing a gas mask, and then was taken to hospital.

He then said he would not negotiate and there would be "no pardon or forgiveness" for those involved in the rebellion.

He also said the police were manipulated by members of the opposition who were trying to stage a coup.

Mr Correa pointed the finger at former President Lucio Gutierrez, who is supported in the assembly by the Patriotic Society Party (PSP).

Mr Gutierrez, who denied the accusation, was prominent in an uprising in 2000 that deposed then-President Jamil Mahuad, and was himself toppled by massive protests in 2005.

Ecuador has a history of popular uprisings, and has had eight presidents since 1996. Mr Correa's government has been the most stable one in a decade - so far.

But given his unwillingness to negotiate and growing social tensions within the country, a new period of instability seems to lie ahead.

- Published1 October 2010

- Published27 February 2013

- Published30 September 2010