Green Party votes up for grabs in Brazil's election

- Published

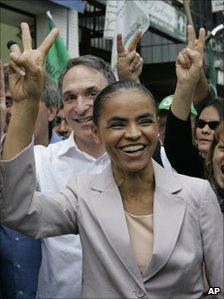

Marina Silva won the votes of nearly 20 million Brazilians in the first round

As Brazil gears up for the second round of its presidential election in two week's time, a key role is being played by a candidate no longer on the ballot paper: Marina Silva.

Ms Silva from the Green Party (PV) came third in the 3 October election behind the two politicians who now go head-to-head, Dilma Rousseff and Jose Serra. But her unexpectedly strong showing to capture a 19% share means there are millions of votes up for grabs.

Ms Rousseff, the Workers' Party (PT) candidate, and Mr Serra of the Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB) are both courting Ms Silva and the Green Party has been promised ministries in whichever administration takes office.

But while Ms Silva has been described as a power-broker, it is clear that she and the PV leadership are split over what position to adopt in the 31 October run-off election.

While party leaders overwhelmingly favour declaring support for Jose Serra, Ms Silva has expressed a wish to remain neutral and insists t is up to the 20 million people who backed her to make up their own minds.

Although Ms Silva stood for the Green Party, she comes from a very different political background from most of its members.

An illiterate rubber tapper's daughter from the Amazon rainforest, she learned her politics from the martyred union leader and forest defender, Chico Mendes, and from progressive priests and nuns of the local Roman Catholic church.

She was an early member of the PT, and won successive elections on the PT ticket.

President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva chose her to be his first environment minister - a job she held for six years before resigning in protest at the lack of support for her forest protection policies.

She joined the PV in 2009, and was chosen as their presidential candidate because she had a much higher profile than any other green politician.

In contrast to Ms Silva's background of poverty and struggle, the majority of Greens are drawn from the urban, upper middle classes.

They identify more with the PSDB than with the PT, and in several states they hold posts in PSDB administrations.

Clean image

Marina Silva's campaign attracted support from voters who belonged to neither the PT nor the PSDB, but who saw her as a more attractive third option, ethically and morally superior to the other candidates.

Marina appealed to many jaded voters

Those backing her included anthropologists and scientists, actors and TV stars, environmentally aware business people, and many young voters disillusioned with the main political parties and the stream of corruption scandals over the last few years in Congress as well as federal and local administrations.

Some 40,000 people joined an online non-party movement, Movimento Marina Silva, and supporters set up Marina Movement headquarters in their homes.

Her membership of a Pentecostal church also brought her support from evangelical Christians.

During the campaign debates, while the other candidates traded accusations, she presented a squeaky clean image, reinforced by her appearance - her hair done up in a neat chignon, her clothes elegant but simple. She often wore white.

Even though many Brazilians may not have understood her earnest talk about the need for sustainability, she came across as someone honest, fresh and different to voters disillusioned with the rough and tumble of everyday politics.

The mainstream media, who overwhelmingly supported Jose Serra, gave Ms Silva ample coverage - not because they agreed with her policies or wanted her to win, but because they hoped she would take votes away from Dilma Rousseff.

Because of Ms Silva, the campaign for the first round was the first time in a Brazilian election campaign that environmental issues were aired - even if the other candidates avoided any detailed discussion of them.

Moral authority

Ms Silva's votes have given her a decisive role in the second round, but instead of the environment, abortion has become the main theme, with videos circulating on the internet portraying Ms Rousseff as a "pro-abortion".

Ms Rousseff has a lead of several points over Mr Serra according to opinion polls

Conservative sectors of the Roman Catholic church have accused Ms Rousseff and the PT of favouring what they call a "culture of death" because the government wanted to decriminalise abortion - at present only legally permitted in cases of proven rape.

More than a million illegal abortions are said to be carried out every year in Brazil. The strength of the anti-abortion campaign means no politician dare speak out and adopt a pro-choice stance.

During the election campaign, because of her religious convictions, Ms Silva declared herself against abortion, but suggested holding a plebiscite on its legalisation. That idea has now been quietly dropped.

On 17 October, the Green Party will meet to decide who, if anyone, to back in the second round.

Ms Silva has wanted to widen this meeting to include representatives of popular movements and trade unions, which in effect would prevent a pro-Serra decision and ensure that her choice - neutrality - wins the day.

She knows that both Mr Serra and Ms Rousseff favour the sort of development that means more roads and dams in the Amazon.

Her hope is that her millions of votes will give her the moral authority to persuade whoever becomes president to listen to her when she asserts that growth and development can be compatible with sustainability.