Chile miners who escaped rockfall feel abandoned

- Published

Unemployed workers asking "who will get us out of this hole?"

Sergio Malebran is worried.

The 52-year-old worked as a driver at the San Jose mine in northern Chile.

Like so many in Chile and around the world, he followed the rescue of the 33 men who had been trapped in the mine since a rockfall on 5 August.

Sergio, who was not on shift that day, is relieved he did not have to go through what they had to endure.

But now that the 33 have been rescued, he thinks it is time people take notice of the uncertainty facing him and the remaining 265 workers and 200 subcontractors who were employed at the San Jose mine.

'Sick with worry'

Thanks to the government's intervention, they have been paid up to 8 October.

And over the last couple of weeks, Sergio was able to make some extra money driving journalists to and from the mine. That money, he says, will last him until the end of the month.

Sergio Malebran is struggling to find a new job

But he has no idea what will happen then. The mine is closed and will remain so for the foreseeable future.

And there are not many job opportunities in Copiapo, his home town, for a man in his fifties.

"My wife is sick with worry, she has stomach cramps and can't sleep because of all the uncertainty," he says.

Sergio tries to put on a brave face for her sake, but if no extra money comes in before November, they will have to sell her car, leaving her stranded in the remote part of the Atacama desert where they live.

Sergio is even more concerned about his 11-year-old niece Anita, who they are responsible for.

"You see, my wife understands, she's worried, but she knows we'll have to cut back," he says.

But Anita, he explains, will not understand if her aunt and uncle do not come for their monthly visit to La Serena, a nearby town where she is going to school.

"And at the moment, there's just no money for a trip down there," he says.

'Abandoned and cheated'

Union representative Javier Castillo says almost all of the San Jose miners are facing money problems.

"We all live hand to mouth here," he says. "We buy most things on credit, and when you say you work at San Jose, well, who's going to give you credit knowing that the mine has closed?"

Javier Castillo wants the government to step in and pay the workers

He says the union has been able to help some of those hardest hit after it received a generous donation from the Australian Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU).

This allowed Javier's union to pay one miner's electricity bill and the university fees for the children of another, he says.

But the funds are now depleted and with so many of its members unemployed, there are no new contributions coming in.

Under Chilean law, the miners are due a month's wages in severance pay for every year they have worked for the company.

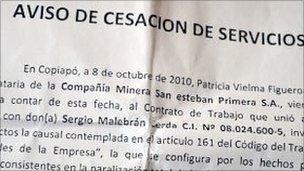

Mr Castillo says they were promised that money with their final paycheck on 8 October.

But with the future of the firm that owns the San Jose still in the balance - an appraiser has been asked to report back to creditors on whether it should be declared bankrupt - the payment has been delayed until at least December.

Mr Castillo is furious. "We need money to put bread on the table now", he says.

"December is a long way off, and even if I were to find a new job straight away, you don't get paid until you've worked there for at least a fortnight. What are we supposed to live off in the meantime?"

He says the miners feel abandoned, cheated even. He believes the government should step in, pay the severance money and recoup the funds from the owners of the mine.

'Interesting offers'

But Undersecretary of Social Security Augusto Iglesias says it is not the government's place to pick up that bill.

He says that while the authorities are working with the appraiser to make sure the workers get the severance payment due to them, they are not there to pressure or interfere.

Workers received their redundancy letters on 8 October

The process has to run its course. In the meantime, he says, the government is helping where it can.

It organised a job fair for the miners last month, which many of the main employers in the region attended.

And, Mr Iglesias says, the amount of job offers made at the fair "was very interesting", although when asked how many miners have since been hired, he says it is only between 10 and 12.

Mr Iglesias says many of the miners were not willing to move to other towns for work.

"This is not a critique. Of course everyone wants to work as close to home as possible, but it makes it more difficult to find work for them," he explains.

Sergio Malebran says the employers were trying to take advantage of the unemployed miners, offering low wages and poor working conditions.

"They wanted us to move far away but wouldn't pay for our accommodation or even the travel expenses," he says. "That just wasn't acceptable."

He does give the government credit for offering free training courses to the San Jose miners, an opportunity he will take, he says, to polish up his CV.

And, unlike Mr Castillo, he stops short of blaming the government for his situation.

"In the end, it's a private company which ran the San Jose mine, so we can't expect the government to pick up the tab," he says.

So what is he going to do, I ask him.

"Have faith," he says, "just like the 33 had when they were underground."

"There is not much else we can do."