Learning to survive in cholera-hit Haiti

- Published

The hospital courtyard in St Marc is full of families caring for their sick relatives

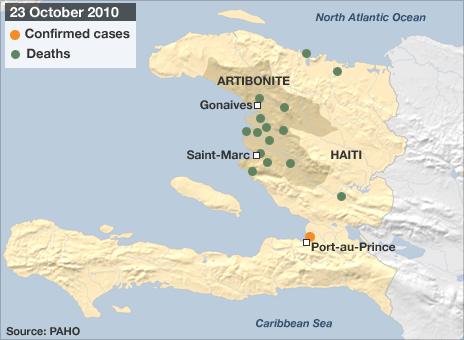

The Artibonite river in Haiti has turned deadly. Once a source of water for the villagers that live along its banks, now it is thought to be the source of the cholera epidemic.

For those who used to bathe, play and do laundry in the river - or drink from it - life has changed drastically.

Aid agencies deliver bottled water daily and leaflets are being given out to the villagers.

"This is very good information," one man tells me, as he reads about how handwashing is important in combating the spread of the disease.

"If we had learned this before, lives could have been saved," he observes.

A mother and daughter who live in a small shed by the river tell me that they lost relatives to the cholera.

"We would never drink that water now," they tell me, looking askance at the river flowing by.

But how do you carry out your daily lives now, I ask.

"We boil the water," they say.

The public information campaign is well underway. Outside St Nicholas' hospital in St Marc, a song blares out from the sound system, encouraging people to use clean water and clean toilets.

There is plenty of bottled water, courtesy of the aid agencies, but clean toilets are another matter.

Human cost

At the hospital itself, there are urns of water on the way in, so people can wash their hands.

People are urged to wash their hands thoroughly as they visit the hospital

A sponge mat on the floor soaked with chlorine is meant to help disinfect the people who might be carrying cholera.

But so many people trample over it, the sponge is turning muddy.

The hospital director tells me he hopes Haitians will now understand just how important basic cleanliness is.

In the crowded hospital courtyard, families tend their sick relatives anxiously, watching the intravenous drips.

The father of eight-year-old Ritchee Camulus is so grateful to the doctors here.

He thought he might lose his son, who had severe dehydration. But now, Ritchee is recovering.

How are you, I ask. Ritchee smiles broadly and asks after me in return.

Cholera can kill within hours. At that back of the hospital I am shown the morgue.

A brand new child's coffin is a poignant reminder of how the most vulnerable are the worst affected by the disease.

I meet Marken in the morgue, searching for the body of his nephew Joseph, who died two days ago.

Haitian authorities hope the epidemic may now be stabilising, but the human cost continues to mount, in a country which has already seen so much suffering.

- Published24 October 2010

- Published25 October 2010