Cholera in Haiti: A charity worker's diary

- Published

Aid agencies are trying to step up their work in Haiti, where a cholera outbreak is now known to have killed 1,344 people since last month.

Aid efforts, especially in the worst-hit areas in the north, were disrupted last week by protesters who blame UN peacekeepers for spreading the disease.

Campaigning is meanwhile in full swing for Sunday's elections despite some calls for a postponement.

Elysia Nisan is working in the Haitian capital for the charity, Save the Children. She will be giving the BBC regular updates on the relief effort.

Tuesday 23 November

While the news is full of stories about Haiti's elections and riots in parts of the country, the side of Haiti I have seen in the last few days is very different.

I met a young boy named Wawins. At 11 years old, he has done something most children in the world never will. He survived cholera.

Wawin who was lucky to survive cholera, sitting with his father, Wiam

When he first had stomach pains, he immediately told his mother. "In school they taught us that as soon as we don't feel good we have to go to a doctor," Wawin explained.

Wawin's father, Wiam Claudel, lives in the Delmas 56 camp. When the cholera outbreak began, we built a cholera treatment unit on the site, where strict protocols are maintained.

Before entering the unit, like everyone else, I had to wash my hands and step through chlorinated water, and do the same on the way out to make sure bacteria did not spread. The unit is a secure location with a friendly and positive atmosphere and 24-hour staff who care for patients.

Wawins stayed at the unit for a few days. He spoke of the help he had received, saying: "they stayed with me during the night and they brought me water."

Having been treated in the unit for a few days, Wawins was ready to get out and go back to school. "I miss my friends, and I like all my classes," he said.

Wednesday 17 November

The number of people ill with cholera continues to go up, and the death rate is alarming to all of us working here.

At this point, we are looking at how we can reduce the rate of transmission as it has already spread to the three main regions where Save the Children works: Port-au-Prince, Leogane (the epicentre of the earthquake) and Jacmel.

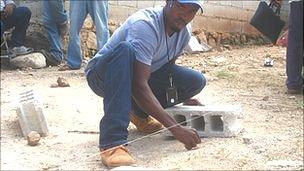

Save the Children staff expand the cholera treatment unit set up at Gaston Margron

These new cases mean we have moved into a new period of the outbreak - where our goal is to lower the death rate, which is currently over 5% of the cases when it should be much less.

The death rate could be as low as 1%, which has been seen in a number of outbreaks in the past. Zimbabwe, however, had an extremely high death rate at its peak - one of the main reasons being because people could not get clean water.

It is our hope that the millions of water purification tablets and the millions of litres of water that have been distributed, along with the latrines being built and the massive information campaign going on across the country will begin to prevent these deaths.

All agencies are working together, sharing resources, co-ordinating efforts - but the work is nowhere near finished.

Sunday 14 November

The discovery of what are now two suspected cases in one of the camps in which we work has raised fears the the number will continue to grow.

A nine-year-old boy and a man are now isolated and receiving intravenous drips to help them recover from dehydration.

What is sad about cholera is that it is both preventable and treatable, and yet it still claims so many lives around the world. Knowledge carries so much power when it comes to beating cholera.

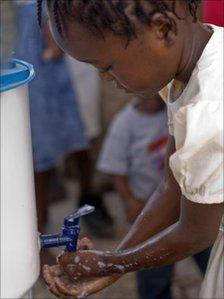

Armed with information, parents can take simple steps, such as ensuring the treatment of drinking water, to protect their children and themselves. It's not only the parents that can play a crucial role. With easy-to-understand instructions, children can become major actors in sharing messages about cholera.

This is why we continue to work with schools, training people to become trainers themselves and distributing soap to children. In Haiti there is an opportunity to allow children to make a difference in combating this epidemic. Everyone can have a role to play.

While this work continues we are not taking our eye off Gaston Margron camp, where construction continues as we prepare for what will likely become a much bigger outbreak.

Thursday 11 November

Since the announcement that cholera is in the capital, work has stepped up a notch.

Education about cleanliness is key

Gaston Margron is a camp of about 18,000 people and Save the Children is the only health care provider there.

So far there aren't any cases at this camp, but it's not hard to see how in the cramped conditions it could hit hard.

One mother who lost a child in the earthquake told me that she knows how to take care of herself.

She carefully washes her hands and makes sure she boils or treats all her water, but she is worried about people who aren't in the camps.

She has a 16-month-old boy. "He is going to be OK," she tells me, "but what about all the others?"

Treatment units are going up, beds are being built. Still the number of cases is climbing as we try to be as prepared as we can be.

Wednesday 10 November

Cholera hasn't surfaced yet in any of the camps where we work but we are preparing for it.

In places where thousands of people are living in cramped conditions with poor sanitation cholera can take a strong hold and spread like wildfire. Poor sanitation and unclean water is how it spreads.

We are informing the public on how they can protect themselves, by washing their hands with soap and only drinking treated water and eating food that has been prepared cleanly.

Preparations are underway in case of an outbreak

We are also equipping our health clinics with additional supplies of oral rehydration salts (ORS), which is the primary action to take when someone gets cholera.

The killer is dehydration, so with enough ORS water they can survive cholera.

We are making sure all our water points are clean and functioning well because they will become very important when cholera surfaces in the camps.

Our staff are focusing on the task of preparing but there is a fear of what may come.

- Published15 November 2010

- Published9 November 2010