Haiti races to stem cholera epidemic

- Published

Contaminated water supplies are worsening the cholera outbreak

Health officials and medical agencies in Haiti are racing to stem a cholera epidemic that has reached the crowded capital Port-au-Prince and threatens to spiral out of control.

The World Health Organization (WHO) says it is struggling to get a clear picture of the situation.

"I wouldn't say it is out of control but it is a huge challenge," said Claire-Lise Chaignat, head of the WHO's global cholera taskforce.

"We know that cases have now reached [the capital] Port-au-Prince, but there are quite a lot of areas we have no knowledge of, for example the rural areas," she told the BBC.

"We are very concerned about the strength of the epidemic in Port-au-Prince because we know that people are living in terrible conditions where the water is very poor quality, there is hardly any sanitation and it is overcrowded. This might be a big outbreak."

'Explosive setting'

Cholera is a bacterial disease spread by contaminated drinking water or food, but is treatable with oral or intravenous rehydration and antibiotics.

Stefano Zannini, Medecins Sans Frontieres' head of mission in Haiti, described the situation as "worrying and complicated".

"At the moment people are focusing on Port-au-Prince, but from the north and the north-west we are hearing of a catastrophic situation with bodies in the streets," he told the BBC.

"Port-au-Prince is probably the most explosive setting, but the situation in other parts of Haiti is not so easy at all."

Mr Zannini said about 400 beds were available in cholera treatment centres (CTCs) across the country and another 600 would be in place by the end of the week.

He said they were also putting up tents in parts of Port-au-Prince where anyone with symptoms can be treated and if necessary be referred to a hospital or CTC.

"We have two big challenges - the first is the lack of medical personnel. The second is getting the information about cholera to the population. Many people are still not aware of the need to go straight to hospital if they are sick."

Ms Chaignat said a priority was to make sure people had access to clean water.

"The situation that the population is living in is absolutely disastrous," she said.

"If we want to stop the outbreak we have to make sure the people don't get contaminated any more and that is by having a safe water supply, and ensuring people use proper hygiene and good food safety practices.

She said that supplies were stockpiled but could become stretched if the epidemic worsens.

"At the moment there is a small proportion of cases who need IV (intravenous) fluids, but if you have 100 cases that on average need 10l (2.2 gallons) you already need 1,000l of IV fluid and logistically that is challenging. Haiti has never had a cholera epidemic before and this is new for everybody."

Alerting population

The British Red Cross has been sending hygiene promotion volunteers door-to-door across refugee camps to advise people how to keep themselves and their families safe.

The agency has also broadcast hygiene advice to hundreds of thousands of people using mobile phone text messages, local radio and newspapers.

Borry Jatta, the British Red Cross sanitation expert in Port-au-Prince, said: "Once people have the disease, treatment is vital, but prevention is the real key. Providing clean water and sanitation, and letting people know how they can protect themselves can cut the chain of transmission."

The agency says it is boosting supplies of intravenous drips, rehydration salts and antibiotics, and delivering 2.5m litres of clean water every day.

"In the camps we can provide those elements, but there are hundreds-of-thousands more living in Port-au-Prince who don't have access to clean water, and who don't have access to decent toilets," said Mr Jatta.

"We are doing all we can, but despite that, cholera in Port-au-Prince still has the potential to be a massive humanitarian disaster."

Medecins Sans Frontieres says its staff are now treating all cases of severe diarrhoea according to standard cholera treatment guidelines.

Hurricane Tomas

More than 70 people are being treated for the disease in the city and health workers say there are dozens more suspected cases.

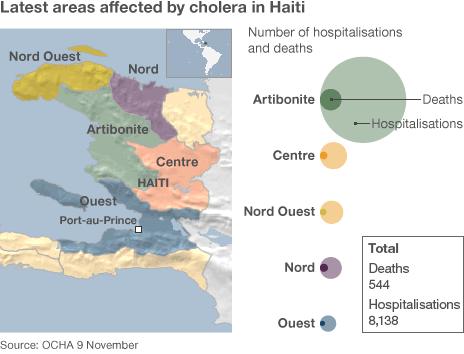

The disease had already killed more than 540 people when Hurricane Tomas swept in last week, flooding areas where earthquake survivors were already living with only basic sanitation.

The storm also flooded rivers including the Artibonite, believed to be one the main sources of the cholera outbreak.

Jon Kim Andrus, deputy director of the Pan American Health Organisation (Paho), warned that cholera transmission in Port-au-Prince was expected "to be extensive".

Gabriel Thimote, Haiti's health ministry director, has said the cholera epidemic was now "a matter of national security".

However, US State Department Spokesman PJ Crowley said he believed the Haitian government's aggressive response, along with the help of international partners, should help contain the disease.

"Tragically, we know that people will die from cholera even though it is a very treatable disease," he said.

"But, through a combination of the improved surveillance, the pre-positioned stocks that are on hand in Haiti, that Haiti is well positioned to contain the outbreak."

- Published23 November 2010

- Published10 November 2010

- Published9 November 2010

- Published9 November 2010

- Published9 November 2010

- Published7 November 2010