Investing hope in Brazil's Suape port expansion

- Published

The rapidly expanding port complex at Suape is swallowing up the surrounding mangrove swamps

The small island of Tatuoca, on the coast of Brazil's Pernambuco state, is not really an island anymore.

The mangroves that separated it from the mainland have been built over with the expansion of the port of Suape and its surrounding industrial district.

It is now possible to drive on a dirt track all the way to a traditional crab fishing village, with some 50 families living in wood and mud houses amid the trees.

In the house of Jose Gustavo a brand-new fridge looks huge and somewhat out of place.

The house has no internal walls, so a wardrobe divides the living room from bedroom. On one side, lies an old-looking mattress but on the other, some of the family's more recent acquisitions - a TV, a DVD player and a video game for the two-year-old son.

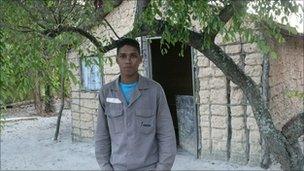

Mr Gustavo, 23, bought all of this on credit over the last two years, since he joined the neighbouring Atlantico Sul shipyard - his first regular job after years of crab fishing and subsistence agriculture.

"I am happy with the way things are changing for me. I believe I will be able to provide to my son much more than I had," says the recently trained mechanic.

"What I need now is a better house because these mud houses we live in are not good. When it rains it drips mud on everything."

'Economic solution'

Jose Gustavo's standard of living has been transformed by the expansion of the shipyard

Investment in the Suape complex is described by the government as key for the development of the Brazilian northeast - the fastest-growing yet poorest area in the country.

Brazilian economy is expected to have grown by 7% in 2010 and its northeastern region by about 9.5%.

The 30-year-old port is going through major expansions and modernisation to accommodate Brazil's ambitious growth expectations.

It will boost the local economy and allow the region's increasingly productive countryside to export produce.

Pernambuco - the state that former President Lula da Silva's family left in the 1950s to escape drought and poverty - will lead the growth with some 11%.

"President Lula da Silva has put the northeast of Brazil back on the development map and investors found it," says the president of the port and Pernambuco's state secretary for development, Fernando Bezerra Coelho.

"Our region is no longer seen as a problem for Brazil, but as part of the solution to the country's challenges."

Mr Bezerra talks proudly of the companies already investing in the area, a list topped by state-controlled oil giant Petrobras, which is building a $13bn (£8.3bn) refinery next to the port.

About 14,000 construction workers staff the site.

More than 100 plants are operating in the district and some 35 others being built. Almost 30,000 people work there.

He says Suape, which handled 15m tones of cargo last year, will reach 45m tonnes by 2015 when new terminals and the railway are ready.

"Our projections indicate that we'll reach 75 million tones by 2030," he beams.

So far, the biggest investment bearing fruit in Suape has been made by shipyard Atlantico Sul - a joint venture between Brazilian contractors and South Korea's Samsung, that have built a $1bn naval cluster from scratch.

"We knew it would be hard to set up such a big project in a region with very deficient infrastructure but we decided that the potential of this location would make it worth," says Atlantico Sul's Gerson Miguel.

"Our main problem is the lack of a qualified workforce for the naval industry."

Environmental concern

To solve the problem, the shipyard has set up it own technical school to fulfil their commitment to hire more than half of its 5,000-strong workforce from the two cities over which Suape lays: Ipojuca and Cabo de Santo Agostinho.

Atlantico Sul is training up people from the local area to work at the port

Students sweat under the heavy safety equipment - essential but very uncomfortable in the heat - for up to nine months, learning the crafts required in the construction of a vessel.

One graduate is Josenilda Maria da Silva, who was trained as a solderer. After three years working on the oil tanker Joao Candido - the first to be built in the shipyard - she was chosen as its mascot.

"I was out of work for five years before I got a job here in the shipyard. Now I make more money than my husband," says Mrs Da Silva.

She loves it when people remembers it was up to her to break the champagne bottle that officially christened the Joao Candido.

"Everywhere around here I hear people saying 'look, there goes the ship's mascot'. I feel very good about this," says Mrs da Silva.

But among environmentalists there is concern about the impact of a project the size of Suape on the delicate mangrove area where it is being built.

"The mangroves are an essential part of the ecosystem because they work as nurseries for sea life," says urban planner and environmentalist Fatima Furtado, from the Federal University of Pernambuco.

"If the mangroves are destroyed we loose an essential breeding ground of nature."

Ms Furtado agrees that expanding Suape is important to sustain the growth of Brazil's northeast but she believes that more could have been done to protect the mangroves.

"The decision was to concentrate the port and a major industrial complex in the same continuous location because this lowers the costs of transport, but the impact on the environment would have been greatly reduced if the factories had been built further inland," she says.

Family relocation

Mr Bezerra is adamant that the authorities are doing everything to reduce the environmental impact of Suape.

He says all environmental licenses and compensation plans have been approved, but that the state cannot forget its development strategy.

"We already have one shipyard there and if we want to build our naval cluster other areas of mangroves will have to be suppressed," he says.

Tatuoca island, for example, is soon to disappear for good, to make room for an expansion of the Atlantico Sul shipyard.

The relocation of the families that live there and the compensations to be paid to them is still in discussion.

The company has hired 50 of the island dwellers - like Jose Gustavo - but many others still live of the traditional crab fishing.

"I don't mind moving but I know many people here are worried. They don't know what to do," says Mr Gustavo.

Fisherman Ricardo Ferreira is among those more worried by the changes than excited. He recently returned to Tatuoca after some time away to find crab fishing had become much harder.

"We see that the place now has electricity and lots of other things but for people like me who still live off the sea it's worse," he said.

"I hope I manage to get a job in the port myself as well."

- Published1 January 2011

- Published29 September 2010

- Published31 October 2010