Haiti's year of living dangerously

- Published

Haiti's earthquake was one of the deadliest natural disasters suffered by mankind in modern times

Haitian journalist Andy Limontas looks back on a year in which crisis has been piled upon crisis following the earthquake in January 2010 that killed more than 200,000 people and devastated his country.

A deadly earthquake, a devastating tornado, a catastrophic cholera outbreak, Hurricane Tomas, and to cap it all an election fiasco in November - 2010 will undoubtedly be remembered by Haitians as a journey through hell.

A year on from the 12 January earthquake which laid waste to much of the capital Port-au-Prince, claiming more than 230,000 lives, the country has not even begun to recover.

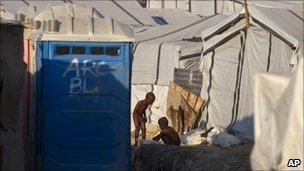

No overall plan to rehouse one and a half million people still living in tents has been made public - despite the creation in New York of an Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC).

This body, co-chaired by Haitian Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive and former US President Bill Clinton, was set up to co-ordinate emergency and development programmes.

Little rebuilding has been done.

The poorest country in the Americas, Haiti has long faced chronic problems meeting its basic needs, and is in a critical condition at the start of 2011.

Blaming outsiders

More than 130,000 Haitians have been infected in the cholera outbreak

Haitians were trying to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives, and dreaming of a hypothetical reconstruction, when a cholera epidemic hit - killing 3,000 people between October and December and infecting 130,000.

Many blamed Nepalese UN peacekeepers based in the Centre region, where the outbreak began.

The Nepalese were believed to have dumped excrement into a river used by locals as a vital source of water.

The idea that the disease was brought into Haiti from outside was later supported by the French epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux, who said: "There is no other possible explanation for the emergence of the epidemic in a country where it was absent."

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has called for an independent investigation into the source of the cholera outbreak, saying it was necessary to "find answers that the people of Haiti deserve".

Nationalist activists were able to capitalise on popular anger against the UN's stabilisation mission (Minustah) and called for its withdrawal.

Protests were held in cities across Haiti, although no-one suggested any alternatives to the multinational force.

The country would arguably be worse off socially and politically without it.

But beyond these allegations, Minustah's presence remains controversial across the board in Haiti.

Many are wondering what its role is, and what exactly is it stabilising.

Unwanted attention?

Many Haitians refer to the UN force as "Touristah" - a joking reference to the casual behaviour of some Minustah members.

But regarding Minustah's presence, Haiti's constitution is explicit: "Security is maintained by two distinct bodies: the armed forces of Haiti and the police forces. No other security corps can be maintained on the national territory."

Some outsiders have questioned more generally the international community's role.

Last month the then-envoy of the Organization of American States, Ricardo Seitenfus, was particularly scathing.

Minustah has been in operation since 2004, but has struggled to stabilise Haiti

He told the Swiss newspaper Le Temps, external that the country had attracted "negative attention from the international system".

The UN, he said, had "frozen power in Haiti and turned its people into prisoners".

International charities, he added, had undermined the authority of the state by maintaining the country in a state of permanent dependency and using it as a humanitarian testing ground.

"It is morally unacceptable to treat Haiti as a laboratory," Mr Seitenfus said. A few days after the interview was published, he was dismissed as OAS representative in Haiti.

Election fiasco

For long-suffering Haitians, presidential and legislative elections were meant to provide a breath of fresh air and a glimmer of hope.

But the outcome has been political stalemate and instability. Baring a last-minute compromise, these will continue for months.

Politicians are not fulfilling their responsibilities. Corruption, which has long corroded public life, was again in evidence during the 28 November 2010 election.

Some stuffed ballot boxes on the eve of the elections, while others resorted to violence and intimidation to get their way.

But international bodies who oversaw the vote - notably the OAS - have their share of responsibility in this fiasco.

"We saw the international community flout democracy and support an electoral farce to promote the catastrophic political status quo that serves its cause," says one student at Port-au-Prince university, reflecting the majority view among Haiti's educated young.

Power hungry

Haiti suffers from a profound and complex disease: its leaders feel no sense of responsibility or duty of care towards their own people.

How much longer will earthquake victims live in tents?

Ever since the fall of dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1986, the high and mighty have been engaged in the merciless pursuit of personal power.

There have been isolated attempts by some political leaders to foster "national dialogue" and promote development.

But these have come to nothing, amid the fight for influence and general chaos.

The international community must find a valid partner to guide its development efforts.

The prevailing chaos has made it impossible for outsiders to be effective on their own.

If their politicians fail to get their act together, the country will forever remain at the mercy of quick-fix operations whose main purpose is to justify the existence of the bodies that launch them.

Currently the country is subsisting on global charity - in sharp contrast with its epic independence movement which broke with French colonial masters in 1804.

If Haiti is to become a proud nation again, its leaders must work to restore the rule of law.

The Haitian people are hungry for positive change. The country needs the decent leaders it deserves in order to breathe free.