Why has so little of Haiti's rubble been cleared?

- Published

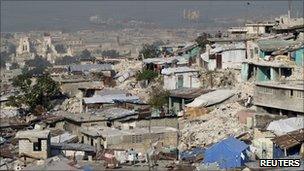

It may have been a year since the devastating 7.0 earthquake shook Haiti, but 12 months on, mounds of rubble remain a constant reminder of the destruction caused by the disaster.

As the Earth's crust shifted in the late afternoon of 12 January 2010, the country's poorly-constructed buildings disintegrated, leaving many of the 250,000 victims entombed.

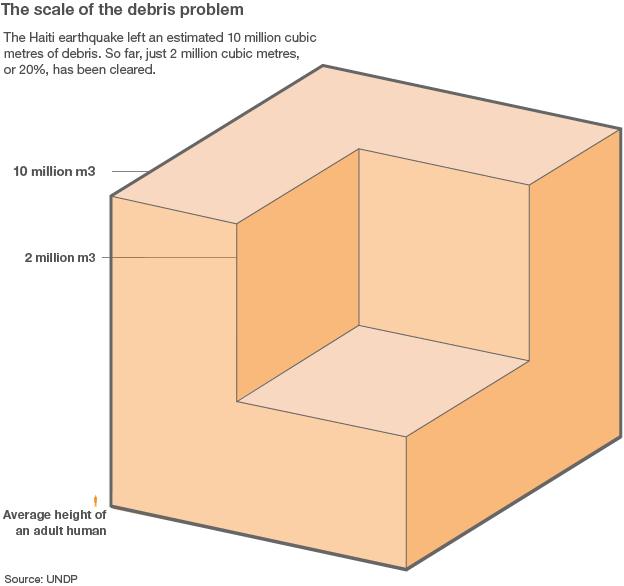

According to the UN Development Programme (UNDP), almost 200,000 buildings collapsed in Port-au-Prince and surrounding areas, creating an estimated 10 million cubic metres of shattered concrete, twisted steel and other debris. This is enough rubble to fill London's Wembley Stadium two-and-a-half times over, or 4,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Few could question the epic scale of the clean-up required in the aftermath of the quake, but one year on, many are asking why just a fifth - or an estimated two million cubic metres - of the debris has been cleared.

Charity Oxfam, external has blamed crippling indecision for the delays, adding that even if the work of removing the rubble continues on schedule, less than half will be cleared by October this year.

Rubble remains an obstacle to reconstruction in many neighbourhoods of Port-au-Prince

But Jessica Faieta, the United Nations Development Programme's (UNDP) senior country director in Haiti, reminds critics that any progress needs to be measured against the magnitude of the problem.

"Ten million cubic metres is - if you are bringing it down it - the equivalent to 10 World Trade Center sites," she says. "It is very large as you can see."

Marcel Fortier, head of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, external in Haiti, agrees, explaining that it would take 200 trucks a total of 11 years to clear all the rubble caused by the quake.

"This is a mammoth task," he says.

Debris plan 'paralysis'

Yet, Ms Faieta and Mr Fortier insist some progress is being made.

Most streets are now passable, and in Leogane - the town at the epicentre of the quake which has much flatter and more accessible geography than the capital - about 80% of the debris has been removed from the downtown area. The whole of Leogane is expected to be clear by the middle of 2011.

Ms Faieta does acknowledge, however, that there was a certain amount of "paralysis" regarding rubble removal during the first half of 2010.

"There hasn't really been a strategy for debris clearance - such as [deciding] where we were dumping the debris," she explains.

Haiti's political instability before and after the country's elections in November contributed to that paralysis, she says, and it took time to choose which neighbourhoods should be cleared first - a decision that has now been made.

In December, the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, external approved $25m for demolition and rubble removal in targeted Port-au-Prince neighbourhoods, and the UN and the International Labor Organization are now working with the authorities on two pilot projects - the first in six selected neighbourhoods in Port-au-Prince and a second in the town of Leogane.

A third project involving nine further areas will start in early 2011.

"These are the neighbourhoods that caused the most displacement and if people are going to be returned, the debris needs to be removed," explains Ms Faieta.

The projects will recycle some of the debris to improve roads, paths and provide foundations for temporary shelters, she says, as well as employ local people, training them in new skills where necessary.

"We must involve communities in the development of their own neighbourhoods," Ms Faieta adds.

But for those on the ground doing the heavy removal work, there are further frustrations.

Confusion over property ownership, the unforgiving geography of Port-au-Prince and its tightly-packed housing are all major challenges, explains Michael Wyrick - one of those contracted by the government to help with debris clearance and building demolition.

As vice president of business development for the Haiti Recovery Group, external, he says one of the biggest obstacles for his team has been obtaining permission from the Ministry of Public Works to enter damaged properties - particularly those of commercial use - as much of the ownership documentation, if it existed, was lost in the quake.

"It becomes ambiguous," Mr Wyrick explains. "Where are these property lines?"

But even when ownership is confirmed, the geography of Port-au-Prince, with its narrow streets and hilly terrain, can make many areas difficult to get to with machinery, he says.

Downtown, street vendors populate roadsides preventing large vehicles maneouvering freely and traders can be reluctant to leave their pitch - even temporarily - to let vehicles through.

'Unique complexity'

And in the capital's neighbourhoods there are other obstacles.

"There are tents blocking streets and in some areas you just have footpaths between buildings, making it difficult to access with heavy machinery," Mr Wyrick says, explaining that in some locations his teams have had to resort to clearing debris by hand.

Another factor making demolition tricky in such neighbourhoods, he adds, is the fact that many buildings categorised as yellow and red - properties that are partially or badly damaged - are located very close to those that have been deemed safe - colour coded green.

Such daily practical difficulties mean the reconstruction work in and around Port-au-Prince will continue to be slow and time-consuming - something the Red Cross's Mr Fortier is keen to remind people.

"I have been in this kind of work for 30 years all over the world, and I have not yet experienced anything of this complexity and magnitude," he says.

"To rebuild a capital city that was not in good shape before will take many years."