Bolivia sees rise in people-smuggling

- Published

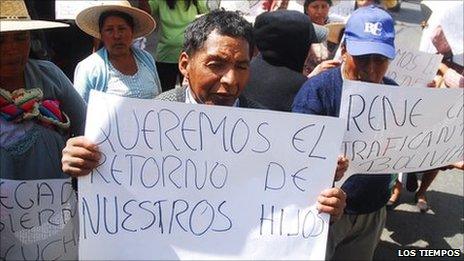

Families' anguish is apparent as they call for the return of relatives in Russia

Juan Rivera couldn't believe his luck when he was taken to Russia with the promise of a guaranteed job and a monthly pay of $2,500 (£1,550).

The 35-year-old Bolivian was among hundreds who replied to an advertisement in the local press for builders to work abroad.

Mr Rivera had been doing seasonal manual work in Argentina.

Travelling to the town of Rostov in Russia seemed like a great opportunity to earn money for his growing young family. His wife was pregnant at that time.

But once in Russia, none of that money materialised.

What awaited him instead were exploitation, overcrowded accommodation and hunger.

A Bolivian court heard and saw evidence of living conditions for those trafficked to Russia

It was then that Mr Rivera realised he had been a victim of human trafficking.

"We had to work for 12 hours a day, even on Saturdays," he remembers.

"They didn't give us a cent; only some food, which we had to share."

During more than two long months in Russia, he worked at a car factory and slept in a tiny room with several other Bolivians.

Mr Rivera said he felt like a hostage. Smuggled into Russia by his traffickers, he was unable to go out on the street for fear of being detained by the police.

Left with debts

Mr Rivera is now back home and is grateful to the Bolivian embassy staff in Moscow.

They helped him and the other victims escape, after a phone call alerted the embassy that more than 200 Bolivians were working without pay and in poor conditions.

But Mr Rivera and hundreds of families were left penniless.

"I had to borrow $9,500 (£5,800)," he says, money he paid his recruiters to go to Russia and used to escape from them.

"I still have to repay [my brother] $7,000," a fortune in Bolivia where the minimum wage is $116 (£70) per month.

Mr Rivera is not an isolated case. Thousands of people have even had to sell their homes to pursue the promise of better opportunities abroad.

Bolivia's Public Ombudsman Rolando Villena says the problem of human trafficking is a "growing reality" that is "fed by mafias and transnational criminals who operate in different countries".

Mr Villena believes that many of the 15,000 children who cross into Argentina alone every year, with their parents' supposed authorisation, are instead victims of sexual and work exploitation.

He also says that, in the Bolivian mining region of Potosi, children are being sold to human traffickers for as little as $3.

Despite convictions for trafficking, the crime is on the rise in Bolivia

President Evo Morales has questioned the ombudsman's allegations, saying he was surprised by the revelation, and asked Mr Villena's office to provide evidence.

But despite the existence of incomplete data about the scale of the problem, the few statistics that are available do suggest that human trafficking in Bolivia, and of Bolivians, is increasing.

According to the police, cases of trafficking went up by 26% between 2008 and 2010.

Official data show that 335 people, mostly children and adolescents, were known to have been recruited by criminals last year.

But human rights groups believe that number is much higher, because not all victims are rescued or come forward.

Sweatshops

Neighbouring Brazil and Argentina are the main destinations for Bolivian migrants and victims of human traffickers alike.

Mario Videla, of Pastoral de Movilidad Humana, a Christian charity, believes young Bolivians are easily lured into fictitious opportunities abroad because of poverty at home.

"Many of these young people can't see a future here," he says. Bolivia is the poorest country in South America.

"So when somebody tells them 'If you go with us, you will work eight hours and gain $1,000 dollars a month', this is attractive for them.

"But when they arrive there, they find out that the conditions [are inhuman] and the money never comes. Some of these people work, eat and live in the same place."

Clandestine factories are frequently dismantled in Buenos Aires and Sao Paulo, where Bolivians live in slave-like conditions.

But these criminal networks also operate within Bolivia. In La Paz, for example, a women's centre looks after children and young adolescents who were rescued in the city.

Fourteen youngsters are currently housed in the Centro de Terapia.

Legal crossings between Argentina and Bolivia but it is the smuggled people who are at risk

Among them is a 15-year-old girl from the city of Sucre who was brought to La Paz to be a domestic worker but was exploited and raped by her employer.

Another girl of 14 years from Potosi was sent by her mother to La Paz to work as a nanny, but ended up doing all the household chores.

She escaped and is now being looked after by the centre.

Since coming back from Russia in 2008, Juan Rivera has resumed working in the construction industry in the eastern city of Santa Cruz.

His traffickers, who include three Russians, continued operating the same recruitment agency in Bolivia until they were arrested by the police two years ago.

They were found guilty by a court in the city of Cochabamba and are now waiting for sentencing, which may mean up to 15 years in jail.

Mr Rivera has set up an organisation with other Bolivians who suffered the same ordeal to help trafficking victims to seek justice.

He has learnt not to believe opportunities that sound too good to be true, and urges people not to make his mistake.

"You must be careful who you get involved with," he says, "because it is a big mess if you are deceived."

- Published8 March 2011

- Published14 December 2010