Poor Brazilian women see job prospects widen

- Published

Barbara Jose Baptista: Proud of her roots and proud of her achievements

Barbara Jose Baptista grew up watching her mother, Odilea, go out to work as a maid, just as her mother before her.

For poor Brazilian women with little or no schooling, domestic service has long been seen not just as natural, but almost inevitable - one of the few employment options open to them.

But Barbara, 24, was determined to make her mother proud - and not follow in her footsteps.

"I didn't follow my Mum's path but that is because she always gave me support and encouraged me to seek a profession that would give me a better standard of living," says Rio resident Barbara.

"Being a maid pays your bills, but you can't progress or learn things."

Barbara's only regret is that Odilea, who died in 2005, did not live to see her graduate in biotechnology and embark on a master's degree that she hopes will eventually lead to a position in cancer research.

Valued at work

"I kept my dream alive", says former maid who became a nurse

Stories like Barbara's are increasingly common as Brazil's economy grows, the number of people living in poverty declines and education levels gradually rise.

Even with a basic education, job opportunities in supermarkets, telemarketing, cleaning companies, restaurants and offices beckon for women who would previously have worked as home helps for a middle-class family.

"They may even earn less (than being a maid), but they have benefits and more job security, and, above all, prospects of growth," says consultant Renato Meirelles, from the Data Popular research institute.

Young people, he says, are increasingly put off the idea of being a domestic servant.

Situations may vary but according to sociologist Luana Pinheiro, the maid-boss (most often maid-madam) relationship is essentially one of submission.

"Although the workload is heavy, the job is simple, so it is never really valued," says Ms Pinheiro, from the government's Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea).

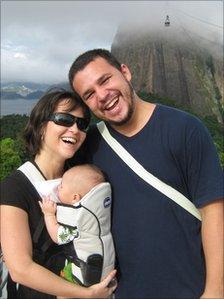

Mariana and Thiago are planning to leave Rio to be able to afford a maid

Angela Conceicao Vaz began working as a domestic servant for a family in Rio de Janeiro at the age of 13 but she always knew she wanted something better.

She attended evening classes to complete her basic education, followed by courses including computing and English.

Now aged 35, Angela has been working as secretary for a telemarketing company for 14 years and owns her own home.

Her eldest daughter, 17, is planning to go to university, and her 12-year-old daughter attends a private school, with Angela paying half the fees.

"They are working for a better future. I am so proud," says Angela.

Rising costs

With fewer women becoming maids, wages - although still low - have been rising.

Salaries vary but are based on the minimum wage which is 545 reais a month ($350, £215).

Many middle-class Brazilian families have been used to having a maid to cook, clean and wash for them, but rising costs mean employing a servant is becoming an unaffordable luxury for some.

And that could mean profound changes - for individuals and society.

Mariana Lago, whose parents always had a maid, admits that she had never done much housework before she got married.

After she and her husband, Thiago, had their first baby they could not afford the cleaning lady any more.

It has been "hell" to cope with domestic chores, work and motherhood, says Mariana, a literature teacher.

"We try to stay organised and keep the house reasonably liveable. But laundry starts piling up, and suddenly the bathroom is so dirty you have to stop everything to clean it."

With a second baby on the way, they have decided to move to a neighbouring city, Niteroi, both to escape rising property prices in Rio and to be able to afford a daily cleaner.

"A maid will be essential for us to take care of the children and keep on working," Mariana says.

'Liberation'

As well as changing individuals' habits, analyst Luana Pinheiro believes the shortage of maids will compel the government to devise child care policies and ways of supporting women in the job market.

Odilea belonged to a generation of women who had little choice but domestic service

The female labour force in Brazil developed with domestic workers at its base, says Marcelo Neri, an economist at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV).

"When women's presence in the labour market grew, women were backed up by domestic maids, who allowed them to leave the house and go out to work."

And many maids themselves also have some kind of help at home to take care of their children or household while they are working.

"The changes we are witnessing in the market will lead to the liberation of domestic maids from unqualified jobs," says Mr Neri.

Barbara, who lives in a poor area in the suburbs of Rio with her aunt, herself a maid, is proud of her humble beginnings - and her success.

She believes she can be a model for others who have not had the same encouragement to aspire to study and seek out better career prospects.

"I'm happy to share this with others, this sense of achievement," Barbara says.

- Published28 June 2011