Colombian girl's kidnap highlights children's plight

- Published

Nohora's family have made repeated pleas for her release

Her name is Nohora Valentina Munoz, she is 10 years old, and for the last two weeks her name has been in the prayers and tweets of many Colombians.

Nohora was abducted on 29 September when her mother was taking her to school in Fortul, a small town near the Venezuelan border.

Her mother was released shortly afterwards but Nohora's whereabouts remain unknown.

Her father, the local mayor, has led the pleas for her safe return.

Tens of thousands of Colombians have also taken to the streets to demand her release, a call echoed by Pope Benedict XVI and Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos.

Some 2,000 soldiers and policemen are looking for Nohora, while the government has offered the equivalent of $80,000 (£50,000) for information about her whereabouts or her captors.

Kidnap hotspots

But while Nohora's plight has hit the headlines, young people have long been at risk of being kidnapped in the country.

"In Colombia there have always been abductions of minors, even though we haven't had such an outcry for long time," said Viviana Esguerra, from the Pais Libre foundation, a Bogota-based non-governmental organisation (NGO)devoted to the problem of kidnapping.

Nohora is not the first young person to be abducted in 2011: officially, 21 such cases had been registered by the end of July.

And in the last three years and a half, the government has recorded 168 such abductions with more than half involving children under 10.

Ms Esguerra stresses kidnapping has declined from a decade ago, when on average eight people were abducted every day.

But with almost two kidnappings a day, the problem is far from over.

Abductions are more widespread in regions like Arauca, where the Farc and ELN rebels operate, and where the paramilitary and drug-trafficking groups are also active.

It is not clear who is behind Nohora's abduction but many Colombians are pinning the blame squarely on the Farc.

Forced to fight

Nohora's face has become the symbol of Colombian children caught up in the long-running civil conflict.

Two out of 10 young people have been affected in some way, according to the Ombudsman's Office of Colombia that oversees the protection of human rights.

Colombia's conflict affects children in many different ways

This includes those who have lost their parents in the conflict or have been forcibly displaced from their homes.

All the illegal armed groups have been accused of the forced recruitment of minors, some as young as seven years old.

The Coalition Against the Involvement of Children in the Colombian Armed Conflict (Coalico) calls forced recruitment "the invisible crime".

There are no exact figures for the number of children involved with the armed groups but it is widely accepted one in four fighters is a minor.

And, according to Coalico, an umbrella group of local and international NGOs, on average young people join the guerrillas when they are about 12.

In some cases, they are snatched from their families by force. But more often than not, they are forced into armed ranks by circumstances.

"It might be that they see it as the only way to become somebody or their only possibility to have clothes and food," Carlos Martinez from Coalico told the BBC.

"They might join to protect their lives and their families' or to escape other threats resulting from the conflict.

"It often is a matter of survival. It's a complex issue."

Stray bomb

In northern Cauca, where the Farc also have a strong presence, the forced recruitment of minors is a particular threat for the Nasas, an indigenous community.

The Nasas are also worried about the risks for their children amid frequent clashes between the rebels and government forces.

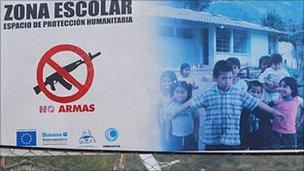

With the support of the humanitarian agencies, such as Echo and Diakonie, the Nasas are erecting wire fences around their schools to try to keep the armed groups away.

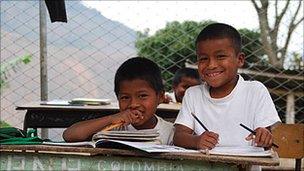

These Nasa schoolboys are among children growing up amid fighting

They told the BBC that soldiers and rebels sometimes enter the schools during fighting, either to look for cover or use the building as a shortcut.

The fighters, local people said, seemed to have no consideration for the children's safety.

Children are not safe at home either.

Last month, an 11-year-old Nasa girl died when a stray bomb felt on her house, in the indigenous reserve of Huellas.

But while most Colombians have heard of Nohora, few have heard of Maryi Vanessa Coicue.

But like Nohora, Maryi's fate symbolises how the conflict in Colombia has affected and continues to affect the country's children.

- Published8 October 2011

- Published3 October 2011

- Published29 August 2013

- Published27 May 2013