Bolivia's Evo Morales faces test as voters elect judges

- Published

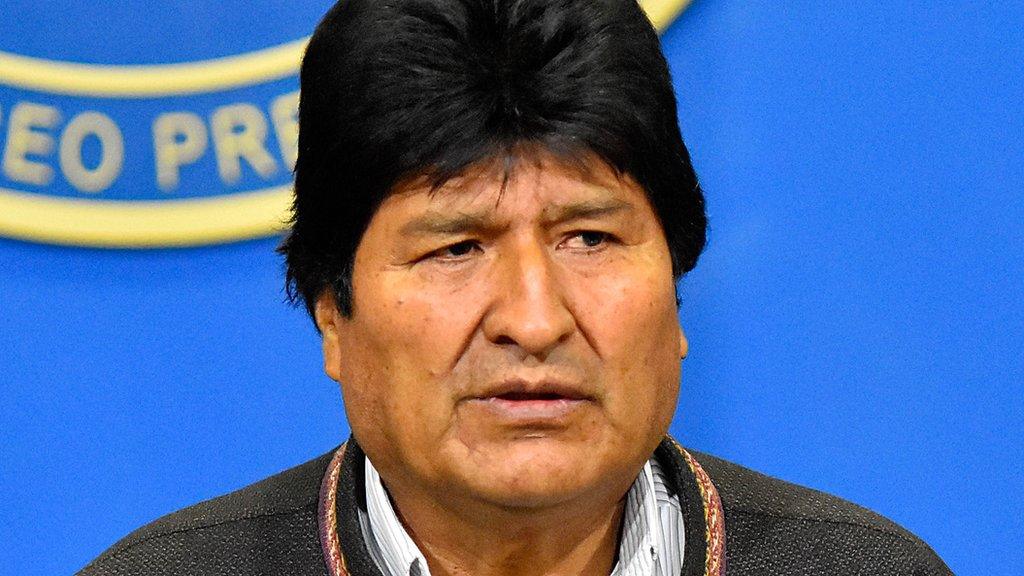

Vocal support for Evo Morales, but the president has seen his popularity slip

More than five million Bolivians are voting to elect all 28 judges for the country's top tribunals, including the Supreme Court.

The vote forms part of reforms pushed by President Evo Morales to give a greater say to the country's indigenous majority.

But the election's focus has shifted away from analysing the judges' credentials to being a vote of confidence in Mr Morales himself.

"I don't agree with or support what the government is doing," says Gabriel Velez, 24, who plans to spoil his ballot to show his disapproval of Mr Morales.

Gabriel Velez (left) and Irazhema Olivera have very different views about Sunday's vote

By contrast, Irazhema Olivera, 29, rejects accusations that the judicial elections will be a farce.

"It's absurd to spoil ballots. Direct elections of our judiciary is political progress," she says.

Bolivia's judges have often been accused of corruption and inefficiency, and there is widespread agreement that the judicial system needs reform.

For the government, these elections will mark an end to the practices of the past, when three or four political parties directly appointed judges.

But although the elections are described as direct, voters are choosing from candidates already selected by Congress, which is dominated by Mr Morale's party, the MAS.

'On merit'

For critics like Carlos Alarcon, a constitutional lawyer, the new system is not an improvement.

"Rather than offering a real choice with real pluralist options, people are going to choose candidates who are likely to be affiliated with the governing party," he says.

Mr Morales is at a key point in his presidency

Other analysts dismiss this concern.

"If Morales's main objective were to control the judiciary, he could have easily achieved this by maintaining the old system," says Kathryn Ledebur of the Andean Information Network, an independent policy think tank.

"The MAS congressional majority could have directly selected all the justices, an unsavoury prospect for the political opposition," she says.

The government insists that all candidates were chosen on merit, and not by political affiliation.

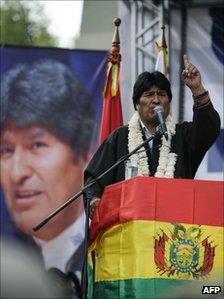

Just days before the elections, President Morales condemned campaigns to invalidate ballots.

"It seems to me a sign of desperation of those seeking the return of colonialism and neo-liberal governments.

"Evo Morales has no candidate for the judiciary because he did not come to the presidency to steal, but to serve the people," the president said.

Betrayal

Juan del Granado, the leader of the MSM opposition party, has led calls for voters to reject the electoral process by writing "No" on their ballot papers.

"MAS has betrayed the electorate and especially our hope that this would be an election of truly independent judges," he says.

"Our vote is to reject and repudiate the candidates of Evo Morales."

The elections come at a trying time for Mr Morales, whose approval ratings have fallen sharply since his landslide re-election in 2009.

There is growing discontent among voters that his government is not delivering on its promises.

The reform of the judiciary is the latest in a raft of changes under Evo Morales

Resentment has also grown following the police crackdown last month on protesters who oppose the construction of a controversial highway through an indigenous territory and national park.

For Franklin Pareja, a professor of political science at the Universidad Mayor de San Andres of La Paz, "the elections will be a good indicator to actually see if the government has lost a significant amount of followers or sympathisers".

"If rejection outweighs support, it could result in a political crisis," he says.

Running again?

But beyond the political repercussions of Sunday's elections, some sectors of Bolivian society are worried about the concentration of too much power in the president's hands.

"The likely scenario [after the elections] will be total control of the legislative, executive and judiciary branches, with the authoritarian effects that result from an exaggerated and excessive concentration of power," says Mr Alarcon.

He believes that Mr Morales could use the new judges to continue what the opposition says is political persecution of the government's critics.

Mr Alarcon also thinks that the president could receive the backing of the Constitutional Court to run for a third term in 2014.

Mr Morales's opponents have called on voters to spoil their ballots

This would run counter to the constitution that Mr Morales himself promoted two years ago.

"It's not enough, what Evo Morales says. He needs an official validation of his interpretation [of the constitution]. And the only official validation would come from the newly-elected Constitutional Court," Mr Alarcon says.

For the government, such fears are unfounded.

"This is an election to guarantee the independence of the judicial authorities," Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linares said.

Ms Ledebur believes that despite concerns the reforms are an improvement on the old system.

"The new process is imperfect, cumbersome and uncharted territory, but it is decidedly more democratic and inclusive," she says.

- Published13 October 2011

- Published10 November 2019