Peru women fight for justice over forced sterilisation

- Published

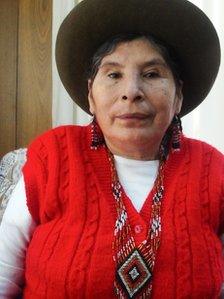

Aurelia Paccohuanca: "I was afraid and nervous"

Peru's government has reopened an investigation into a controversial birth control programme of sterilisation. The announcement has brought fresh hope to the many women and men who feel their rights were violated.

"You give birth like pigs or hamsters!"

Aurelia Paccohuanca remembers those words uttered by nurses when she opposed what was being presented as a solution to Peru's extreme poverty.

"Because I already had four children, they told me I couldn't have any more. But I said I didn't want to be sterilised," says Ms Paccohuanca.

It was October 1998, in the countryside near Cuzco, a poor and predominantly Quechua-speaking area of the Peruvian highlands.

After weeks of trying to avoid them, Ms Paccohuanca was confronted by the nurses again.

"I was running away from them," she says, "but they caught up with me, and got me inside the ambulance against my will."

Ms Paccohuanca says she was driven to a clinic, and told to enter a room.

"They ordered me to take off all my clothes. I was afraid and nervous. And I started crying."

An independent congressional commission established in 2002 that the government of Alberto Fujimori had sterilised 346,219 women and 24,535 men in the last seven years of his presidential mandate (1990-2000).

It was part of an attempt to reduce the country's birth rate. Lowering the number of mouths to feed, it was argued, would help parents lift their families out of poverty.

But Ms Paccohuanca says her rights were violated. She is one of hundreds of people who have alleged that they were forced to undergo operations and not told they could have refused.

The former president is now in prison, but his convictions relate to Peru's internal conflict, not his birth control campaign.

He has never been tried over human rights abuses allegedly committed during the voluntary health programme. But the testimonies are hard to ignore.

Hilaria Supa knew something was wrong from early on. She is now a politician, and started campaigning for answers in 1996, when she began to receive reports of abuses.

"Some of the women did get sterilised voluntarily," she says. "But they always say they were deceived.

"Some are Quechua and don't speak Spanish. They are illiterate.

"They weren't told or didn't know what the operation really was. At times they were told they would be charged if they had more children."

The sterilisation programme enjoyed the backing of international donors including the United Nations Population Fund, Japan and the US, as well as anti-abortion and feminist organisations alike.

"Fujimori used to say: 'Women will have the right to decide whether to have children or not,'" says Maria Ester Mogollon, a campaigner who works with Hilaria Supa.

"As feminists, we thought it was a good idea.

"But that changed when we started getting information that it was all done through force, with threats and police involvement."

'No quotas'

Marino Costa Bauer, a health minister at the time, admitted that it was evident that errors had been made by his department.

Hilaria Supa has been campaigning for years on this issue

He revealed in 2002 that there had been no regulations setting out how the sterilisation programme should be implemented, but said that it was a problem he had tried to fix.

"We published national guides on reproductive health," he said. "They were designed to train all medical staff, especially those working in family planning."

Members of the Fujimori government also tried to shift some of the blame onto doctors and nurses, saying that some might have been unscrupulous.

Officials insisted that medical staff did not have quotas to meet, nor did they receive bonuses for reaching targets.

Gloria Cano, however, believes the campaign was a premeditated and racist state policy. She represents many of those women at Aprodeh, a Peruvian human rights organisation.

"We're talking about a problem that has affected poor and indigenous women for the most part," she says.

"It was disregard for the poorest people, not medical negligence."

Luis Alberto Salgado, Peru's public prosecutor, admits it would be difficult to establish whether the programme constituted genocide.

But he believes that a judicial investigation would determine whether there was criminal intent behind the programme and "whether state ministers knew or should have known that sterilisations were being carried out by deceit, threats or coercion".

Previous investigations have been archived because of judicial loopholes and apparent lack of evidence. And no court has yet ruled on the case or ever sent anyone to prison.

But Aurelia Paccohuanca is determined to carry on.

Thirteen years after the operation, she can no longer farm the land because of health complications, and recently she had to have her uterus removed.

"If they hadn't done that to me, the sterilisation, I would have lived happily with my family.

"We are going to fight till the very end, until we get justice."