Peru's Shining Path rebels: Old enemy, new threat

- Published

The recent arrest of a Shining Path leader was a major blow to the group

Jiron Tarata is a narrow street in the heart of Miraflores, the business district of the Peruvian capital, Lima.

Restaurants and shops alternate with the shaded entrances of residential buildings.

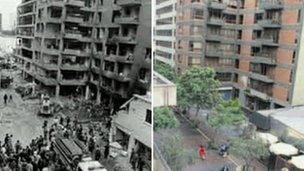

Today, this is a pedestrian walkway. But on 16 July 1992, when it was a road open to traffic, a car bomb caused massive devastation.

"It was a Thursday, at 9:05 in the evening," says Gregorio Ramiro, who still works as a porter in one of the buildings.

"The first explosion was to attract attention," he says.

Mr Ramiro, like many others on the street, went to the windows to see what had caused the loud noise.

Now 20 years on, the physical marks of the 1992 bombing are long gone

Standing there, no-one escaped what came next.

"The second blast was the horrible one. That's what caused the carnage."

Twenty-five people died and dozens more were injured.

The blast was so powerful that it threw Mr Ramiro back several metres. He still has visible scars on his face and arms from the sharp glass that cut and pierced his skin.

Everything - windows, doors, furniture - was blown off. Only the skeleton of the buildings was left standing.

One resident still gets teary when she remembers what happened.

"There were people crying and moaning," says Maria Teresa Passarelli.

"This was worse than an earthquake, because a quake is a natural phenomenon.

"This was something that came from the evil of human beings."

Feared fighters

The bombing was the deadliest by the Shining Path guerrilla movement, at the height of its attempt to overthrow the government.

Two months later, its founder and leader, Abimael Guzman, was arrested. And with his capture, the strength and influence of the Maoist organisation was severely weakened.

Today, only a few pockets of resistance remain.

A leader of Shining Path remnants, known as Comrade Artemio, was captured in mid-February.

Many Peruvians accept that the guerrilla group no longer poses a serious threat to the government unlike before when its fighters tried to install a Communist state.

But while the movement is still listed by the US and the European Union as a terrorist organisation, experts suggest its goals have changed over the years.

"[The capture of Artemio] was not a blow to terrorism," says Jaime Antezana, an expert on the subject.

"It wasn't the final thrust against the terrorist subversion. This was a blow to drug-trafficking."

Fernando Rospigliosi, another leading analyst and a former interior minister, agrees.

"After Abimael Guzman fell, the groups that remained converted more and more to drug-trafficking.

"They kept their political discourse, but that's an excuse for what they really are.

"These are people who live off drug-trafficking."

Drugs strategy

The link between the Shining Path and illegal drugs is widely documented.

Comrade Artemio, whose real name is Florindo Eleuterio Flores Hala, has been charged with terrorism but also drug-trafficking.

Cocaine production is increasing in Peru

The two areas where Shining Path rebels are still active, the Alto Huallaga and Ene-Apurimac valleys, are also the regions where most of Peru's cocaine comes from.

Mr Antezana believes that, to this day, no government has had the serious political will to tackle Peru's drug problem, and that, more than six months into his presidency, nothing is changing under Ollanta Humala.

"What we have heard [from the government since the capture of Artemio] is that the priority in Peru is the fight against terrorism," he says.

"That means that they will just try to dismantle the armed structure [of the Shining Path].

"Meanwhile, drug-trafficking keeps on going up."

The Peruvian government has recently approved its counter-narcotics strategy for the next five years.

Forceful eradication of coca - the raw material for making cocaine - will continue.

The government also promised it would seize more drugs, fight money-laundering more efficiently, and control better the flow of chemicals that can be used for making cocaine.

But Mr Rospigliosi is sceptical that this will work.

"All politicians do is talk, talk, talk, but they don't do anything. Drug-trafficking is much more difficult to combat than the Shining Path," he says.

"There are too many people involved who have a lot of money. And there's a lot of corruption [in state institutions]."

"All they can do is contain the problem."

The days of bombings such as the one in Tarata are over.

The police in Miraflores now fight petty crime, not armed insurgents. And cheap cocaine is the drug of choice among many revellers at the district's nightclubs.

Cocaine production is up in Peru, and the country is slowly surpassing Colombia as the top exporter of the illicit drug.

The Shining Path is part of the problem, but no-one can predict which form it will now take following the capture of Artemio.

But Mr Antezana and Mr Rospigliosi both say that until the government shows serious leadership and puts more resources in the fight against drug-trafficking, the armed group will not disappear.

- Published28 February 2012

- Published23 June 2011

- Published7 December 2011

- Published20 July 2011