Ecuador seeks answer to riddle of Inca emperor's tomb

- Published

Does the final resting place of Inca Emperor Atahualpa lie here?

The mystery surrounding the tomb of the last Inca emperor - and its reputed treasure - might be closer to being solved.

If Ecuadorean historian Tamara Estupinan is right, Emperor Atahualpa's mummified body was kept in the lush, hilly lowlands, a six-hour drive south-west of Ecuador's capital city, Quito.

While it is still too early to confirm Ms Estupinan's theory, this discovery could shed light on a tumultuous historical period that marked the beginning of the Spanish colonial era in the Americas.

At its height, in the early 1500s, the Inca empire covered most of the Andes, from southern Colombia to central Chile as well as some parts of Argentina.

Inca emperors were mummified because it was believed that their powers remained within their bodies, which were guarded by guards and family members.

Atahualpa governed out of Quito during a civil war against his brother, who was based in Cusco, the seat of the Inca empire.

Some 40 years after the death of Atahualpa the Inca empire had fallen

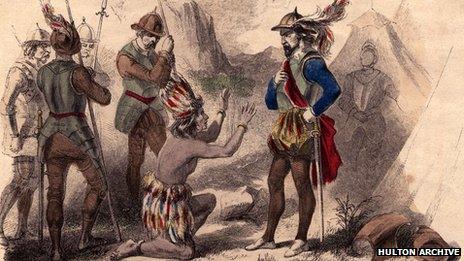

Shortly after defeating his brother, Atahualpa was captured by Spanish troops under Francisco Pizarro.

It is believed that Atahualpa offered to fill a large room with gold and silver in exchange for his life. The offer did not work - he was executed in 1533.

End of an era

The Inca empire began to fall apart after his death, leaving only pockets of resistance against the Spanish conquerors.

Archaeologists and historians have questioned whether his body remained in Cajamarca, the city in northern Peru where he died. No tomb was ever found.

But Ms Estupinan, a researcher at the French Institute for Andean Studies (IFEA), says historical texts contain clues that indicate that the Inca emperor's final resting place was in what is now Ecuadorean territory.

The historian's work focused on Ruminahui, one of Atahualpa's most loyal generals who led a revolt against the Spanish conquerors after the emperor's death.

During her research, which lasted more than a decade, Ms Estupinan came across evidence that suggested that the Sigchos area in Ecuador's Andes became a base for Ruminahui and his men.

She started looking for locations whose names were connected to sacred rituals.

In 2004 she came across a small farm named Malqui - a word that means "mummy" in Quechua, the language spoken by the Incas.

The shape of the stones suggest a link with the Inca tradition

Polished stone walls and a subterranean water canal indicated the Inca origin of the site.

Six years later, Ms Estupinan led a new expedition some 4km (2.5 miles) from Malqui.

"When we arrived here, I could not believe it," said Ms Estupinan during a recent visit to the site, known as Machay (a Quechua word meaning burial).

A trapezoidal enclosure leading to rectangular rooms that were built with cut polished stone led Ms Estupinan to think that she had reached an Inca monument. The presence of trapezoidal underground water canals served as confirmation.

"I started running around," she says. "It was extremely exciting."

Ms Estupinan believes Malqui and Machay were part of an Inca settlement set up to hide Atahualpa's mummy and his possessions, which were traditionally buried with the emperor, from the Spanish conquistadors.

Machay is aligned with other sacred Inca sites, such as the Quilotoa lagoon, and is surrounded by the Machay River. Running water was important in sacred Inca places.

The site is 1km (3,280ft) above sea level, in the sub-tropical lowlands on the western slopes of the Andes.

Given the humidity, it is unlikely that remains of the mummy could be found intact almost 500 years later.

Excavation works are expected to start in June, partly financed by Ecuador's government, which plans to invest $97,500 (£60,000) in marking and protecting the site.

Historian Tamara Estupinan has been piecing together the evidence

"For now the government cannot yet say whether this is Atahualpa's grave," said Joaquin Moscoso, of the Heritage Ministry.

"If the historian's hypothesis is confirmed, we would be facing one of the largest and most unusual discoveries of the past decades."

Treasure trove 'unlikely'

Unlike in Peru, where much attention goes to Inca sites, such as world renowned Machu Picchu, Ecuador's archaeological ruins attract a limited number of tourists, and government spending is limited.

So far a police officer has been deployed to protect Machay from possible looters attracted by the legend of Atahualpa's treasure.

According to Ms Estupinan, it is unlikely that riches would be found.

"For the Incas, the real treasure was the mummy itself," she says.

Ms Estupinan also stresses that more attention should be placed on the site's conservation.

Pictures of Machay from the 1960s show clear deterioration of several walls.

The site was used to raise fighting cocks and to farm fish.

Machu Picchu, rediscovered in 1910, is now one of the "new" wonders of the world

This year's heavy rains have taken their toll, with the destruction of a large portion of a wall, says Ms Estupinan.

Francisco Moncayo, who owns the Machay site, says he is waiting for money from the municipality to help him keep the place in order.

He says the cost of maintaining the site runs to $3,000 (£1,800) a year.

Jorge Yarad, one of two owners at Malqui, says he feels honoured to be in an Inca site, but he is worried about looters.

"It is a great responsibility," he says.

Mr Yarad hopes the government will be able to buy the land to build an archaeological site that would become world renowned.

"We have been sleeping with history," says Mr Yarad. "And only now are we waking up."

- Published15 December 2011