Chile's military rule 'disappeared' on electoral roll

- Published

Lorena Pizarro's goal is to find out what happened to her father

Waldo Pizarro's family have not seen him since 15 December 1976, when he was abducted in Santiago, a victim of Gen Augusto Pinochet's feared secret police, the Dina.

And yet, Mr Pizarro is eligible to vote in this weekend's municipal elections in Chile. His name appears on the electoral register.

The same is true of Oscar Rojas, from the northern city of Iquique, who disappeared in December 1981 aged just 29.

And of Victor Diaz, abducted by the Dina in May 1976 after more than two years in hiding. He is registered to vote in his home city of Ovalle.

In all, about 1,000 people who "disappeared" during the Pinochet regime between 1973 and 1990 are eligible to vote this Sunday. Their relatives say their inclusion on the electoral register is a sick joke that adds insult to the considerable injury their families have already suffered.

"The Chilean state is saying that my father can go and vote," said Lorena Pizarro, Waldo's daughter.

"And I'm asking in reply, 'Where is my father?'"

Murky history

This situation has come about due to a change in Chile's electoral laws. Until this year, Chileans had to register voluntarily if they wanted to vote but now all those aged 18 or over are registered automatically.

That includes the disappeared because, in the eyes of the law, they are still alive. So, people who have not been seen for decades have suddenly popped up on the voting register.

Chile's electoral service says there is nothing it can do about this. It cannot erase the names because to do so would effectively declare the disappeared as dead, which it is not authorised to do.

The issue highlights the problems that countries such as Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia and Guatemala face when dealing with their murky pasts.

It is difficult enough to bring the perpetrators of human rights abuses to account or to adequately compensate their victims, but dealing with the disappeared is even trickier, human rights lawyers say.

"When a person disappears they are left in judicial limbo, with an unknown legal status," said Ariel Dulitzky, an Argentine member of the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances.

As one example of the many consequences this can lead to, Mr Dulitzky said he had come across cases in different Latin American countries of disappeared people being taken to court for failing to keep up with their mortgage payments.

With no death certificate and no body, it is difficult for their relatives to prove that the person in question can no longer pay.

And, in addition, how do you inherit your parents' estate if you cannot prove they are dead? How can you remarry if you never divorced your wife or husband and they are still, legally, alive?

Declared dead

In the past, relatives of the disappeared dealt with these problems by having their loved ones declared "presumed dead". A death certificate was then issued even if there was no body.

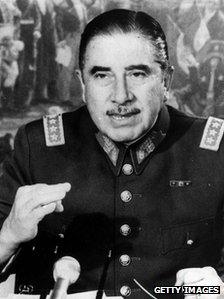

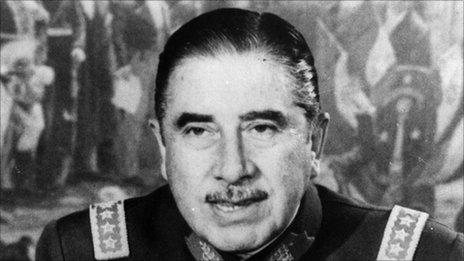

Gen Pinochet ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990

But many in Chile were - and still are - reluctant to do that. They say it would make them feel complicit with the Pinochet regime.

"I won't declare my father dead because I want them to tell me what they did with him," said Ms Pizarro, president of the organisation that represents relatives of Chile's disappeared. "They were the ones who took him from us. It's their responsibility to tell us what happened."

In recent years, things have become a little easier for these relatives. In 2009 the government of Michelle Bachelet - herself detained under the dictatorship - passed a law allowing them to inherit their parents' wealth without a death certificate and dissolve their marriages without divorce papers.

"If you compare it with Brazil or El Salvador or Honduras in terms of justice it's impressive what Chile has done so far," Mr Dulitzky said.

"The amount of money that Chile has paid out in reparations to relatives of the disappeared is probably higher than in any other country in the world," he adds.

But Ms Pizarro wants the state to go further by giving the disappeared a legal status of their own, as they have across the border in Argentina, where about 30,000 people were killed or disappeared under military rule between 1976 and 1983.

"We need a new law that recognises that in Chile there are citizens who are alive, citizens who have died and citizens who are absent due to forced disappearance," she said.

'Deserves respect'

Nearly four decades after General Pinochet came to power in a bloody coup, Chile is still grappling with the legacy of his rule.

Just last year, the state recognised 30 new cases of forced disappearance or murder dating from the Pinochet years, and nearly 10,000 new cases of torture.

More than 1,400 investigations into alleged human rights abuses dating from that time are ongoing.

According to Amnesty International, 245 former members of Chile's armed forces were convicted of human rights abuses between 2000 and 2011, although it points out that barely a quarter of them - 66 - are actually behind bars.

Waldo Pizarro, who was a senior figure in Chile's Communist Party in the 1970s, would be 78 years old if he were alive today.

"I have a lot of memories of him," Ms Pizarro said. "He'd take us for bicycle rides or walks up in the hills where we'd hunt for spiders.

"He was a brave man, but bad-tempered at times. He was no saint, but he was a human being. A human being who deserved respect."

- Published20 November 2017

- Published18 August 2011

- Published19 July 2011