How Brazil tackles scourge of child malnutrition

- Published

Wyre Davies has been to Rio de Janeiro to find out what is being done there to tackle poverty and hunger

How to tackle the deadly threat of child malnutrition is the focus of a meeting of world leaders, scientists and civil society in London on Saturday. Ahead of the conference, the BBC's Wyre Davies reports from Brazil - one country that has seen considerable success in the fight against child hunger and under-nutrition.

Although it may boast one of the world's largest economies, Brazil still has a hugely unequal society - but things are changing. The fight against poverty and malnutrition starts right at the beginning.

At an intensive care neo-natal unit in a Rio de Janeiro hospital, four-day-old Sofia lies in an incubator.

The tiny baby is fed calorie-rich breast milk through a tube. But the milk is not from her own teenage mother. Like thousands of premature babies in Brazil, Sofia is kept alive thanks to donated milk.

In another section of the hospital, other mothers sit and chat. Some are feeding their babies but some are also using mechanical or manual pumps to express milk.

A small army of mothers give their surplus milk as part of a scheme in which generations of Brazilian women have been encouraged to participate for the good of wider society.

One mother tells me she heard about the scheme through friends and work colleagues. So when she had a baby of her own and found that she was able to produce more than enough milk for her own baby, it made sense to give to those, like Sofia, who are in need.

'Nutritional revolution'

There are now more than 200 human milk banks across Brazil - the largest and most effective programme of its kind in the world. Danielle Silva, a quality control co-ordinator for the Brazilian Network of Human Milk Banks, says it's a relatively cheap scheme to administer.

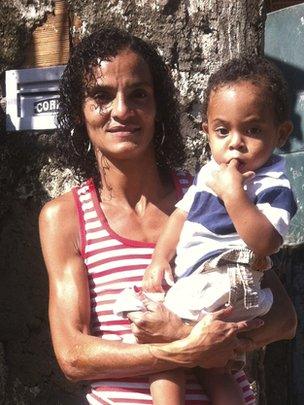

Poor families like Ana Cristina's can put nutritious food on the table thanks to government schemes

"Mortality rates are going down and breast-feeding rates are going up," Ms Silva tells me.

"The Brazilian government actively promotes these policies, supporting us financially and with promotional campaigns."

According to the Lancet medical journal, poor nutrition is the root cause of the death of more than three million children globally every year.

While the main focus is making sure that children from poorer backgrounds are fed well at school and at home, the goal has to go beyond just keeping people out of poverty says Brendan Cox, policy director at Save the Children.

"We know that malnutrition accounts for almost half of all child deaths but it also holds back the development of individual children, it changes the way the brain develops and makes it harder to read and write," says Mr Cox.

In the huge sprawling favela of Cidade de Deus (which gave its name to the famous film of the same name) we met Ana Cristina and her six children. They barely fit into their tiny one-bedroom home.

Ana had just returned home after picking up her youngest son, Marcos, from school. There, he is not only taught but also receives two meals a day - healthy food fulfilling nearly all of his daily nutritional needs.

But Ana Cristina also receives the "Bolsa Familia", or the Family Allowance. It is the main pillar of the Brazilian government's efforts to improve the purchasing power of poor families.

With her Bolsa Familia card Ana Cristina gets about $150 (£100) a month, but to qualify for the scheme her children have to attend school and they're meant to be properly fed.

"We buy rice, beans - enough for everyone," says her husband Marcos - proudly showing me pans with beans and vegetables on the cooker and a bowl of fruit on the table. The children look healthy and happy, despite their meagre living conditions, although for the youngest son a bowlful of jelly was more appealing than the fruit.

Brazilian lesson?

Brazil has already surpassed the Millennium Goal of reducing the number of child deaths by 73%, indeed the government claims that people of all ages now benefit from what amounts to a nutritional revolution.

Mothers donate surplus milk to help other babies in need

On the outskirts of Cidade de Deus men, women and children at a community restaurant were benefiting from sugar- and salt-free food, lots of veg and fruit juice for less than a dollar day.

Brazil still has millions of people living in poverty, and subsidising the basic needs of so many people is not cheap.

But it all comes down to basics. Better-fed, healthy people contribute more to a country's well-being.

Malnutrition does the opposite, costing lives and resources. So what can the rest of the world learn from Brazil?

- Published6 June 2013

- Published28 May 2013

- Published23 January 2013