Chile still split over Gen Augusto Pinochet legacy

- Published

Polls show Chileans are divided in their views of Gen Pinochet's years in power

It often comes as a surprise to foreigners visiting Chile to discover that Gen Augusto Pinochet still has supporters here.

Outside Chile, the general is almost universally vilified - remembered as a ruthless dictator whose military regime killed more than 3,000 political opponents, tortured many more and drove thousands into exile.

But inside the country, views tend to be more nuanced.

As the country marks the 40th anniversary of the military coup that brought him to power, attitudes towards Gen Pinochet's 1973-1990 regime and the Socialist government of Salvador Allende that preceded it remain complex and subject to intense debate.

While most Chileans abhor the human rights abuses committed under his rule, Gen Pinochet still has a small but ardent group of right-wing supporters who regard him as a hero.

They say that by ousting Mr Allende on 11 September 1973, the military prevented Chile from sliding into civil war and saved the country from becoming "another Cuba" - a communist state.

"The armed forces saved me," right-wing congressman Ivan Moreira told Chilean state television this month. "They saved me from living under a regime, a Marxist dictatorship. Pinochet saved the lives of an entire generation."

When Gen Pinochet died in 2006, about 60,000 people turned up to file past his coffin and pay their respects. Some were in tears. Others clutched bronze busts and photographs of the general.

Thousands of people held overnight vigils when Gen Pinochet died in 2006

To this day, there is a museum in Santiago honouring his memory. It contains his military uniforms, his desk, his medals and his extensive collection of toy soldiers from the different regiments of the Chilean army.

Mr Moreira says the Pinochet regime has had a bad press.

"How long are we going to carry on accepting that the history of Chile is written by the pen of the left?" he asked.

Mixed views

"I'm a child of the dictatorship," said Karen, a Chilean I met recently in Santiago.

The Pinochet museum in Santiago houses busts and paintings of the late general

"I grew up with both sides of the story. My godmother is a communist but my mother is pro-Pinochet. They are best friends but they never talk about politics. Never.

"I don't believe the dictatorship was that bad," Karen told me. "It was a safer time on the streets for normal people. Now you go to the outskirts of Santiago and there are lots of drugs. There weren't back then.

"Some young people who didn't live through the dictatorship think that everything about it was bad. People of my age, who experienced it, can remember the good and the bad."

A survey published by pollster CERC, external on the eve of the 40th anniversary commemorations gives some idea of where Chileans stand on these issues.

While three-quarters of those polled said Gen Pinochet was a dictator, 9% said he would go down as one of the greatest leaders in Chilean history.

According to the poll, 55% of Chileans regarded the 17 years of the dictatorship as either bad or very bad, while 9% said they were good or very good.

More than a third of those polled either had no opinion or regarded the dictatorship years as a mixture of good and bad.

Another poll, published in the country's leading newspaper El Mercurio on Sunday, asked Chileans if the state had done enough to compensate victims of the dictatorship for the atrocities they suffered. While 30% said yes, 36% said no. The rest were undecided.

Nearly half of those polled (46%) said the state should find new ways of compensating relatives of the disappeared - victims of the dictatorship whose corpses were often dumped at sea or buried in unmarked graves. But over a quarter (27%) disagreed.

Ideological split

Right-wing historians in Chile use two basic arguments to defend the legacy of the Pinochet regime.

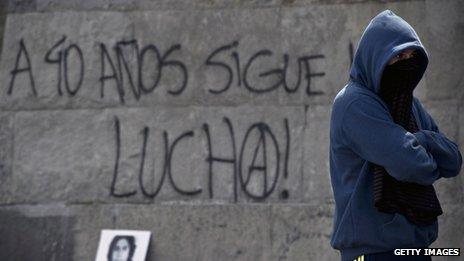

Opponents of the Pinochet regime have been demonstrating in Santiago

Firstly, they say the coup has to be understood in the context of the time - that by 1973 Chile was a deeply polarised country on the brink of civil war and economic collapse.

Secondly, they say that the free market reforms implemented by the military government in the 1970s and 1980s laid the foundations for the country's later economic prosperity.

It is true that by 1973, Chile was in a sorry state. Mr Allende had been in power for three years and the country was increasingly split along ideological lines.

A series of strikes by truck drivers and copper miners had weakened the economy. Right-wing paramilitary groups were sabotaging power lines and transport routes. Basic provisions like bread and flour were scarce.

"As early as December 1971, women took to the streets in what became known as 'the march of the empty saucepans' because of the problems they had getting hold of basic goods," says Adolfo Ibanez, a historian and columnist for El Mercurio.

"And in 1972 and 1973 the situation got worse."

Evelyn Matthei, a right-wing candidate in forthcoming presidential elections, said this month that by September 1973, "the immense majority" of Chileans wanted to see the back of the Allende administration.

Economic success

The reasons for this animosity and for the economic turmoil of the time are still hotly debated.

Some Chileans say Gen Pinochet was behind the country's economic success

The right says Mr Allende's government was incompetent. The left says Chile's powerful and conservative business lobby, backed by covert funding from the United States, undermined the government.

It was against this backdrop that the coup took place.

After assuming power, the military government opened up the economy to the free market.

Foreign mining companies, the assets of which had been expropriated under Mr Allende, were invited back into the country. State-owned companies were sold off. The education and pension systems were privatised.

The right says these reforms helped Chile become what it is now: one of the wealthiest countries in Latin America.

Just how much of Chile's prosperity is down to the policies of the Pinochet regime, and how much is to do with the policies of later centre-left governments and the country's vast mineral wealth, is still a matter of debate.

Human rights

This week's 40th anniversary has rekindled the debate in Chile over the rights and wrongs of the coup, the shortfalls of the Allende government and the legacy of military rule.

Thousands were tortured at centres such as Villa Grimaldi, now a memorial

Ultimately, though, for the outside world, the Pinochet regime is likely to be judged on its human rights record rather than its economic achievements.

According to official figures, 40,018 people were victims of human rights abuses under the dictatorship and 3,065 were killed or disappeared.

That remains by far the biggest stain on the Pinochet legacy.

- Published6 September 2013

- Published5 September 2013

- Published6 February 2013