Defiant notes: The choir founded in Chile's detention camps

- Published

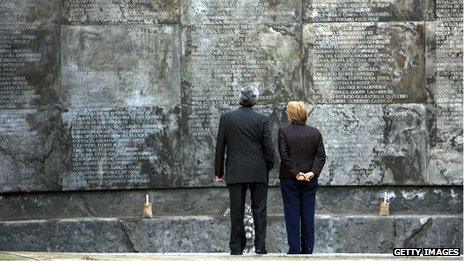

The names of female political prisoners who were executed or disappeared are remembered in a rose garden at the former torture centre at Villa Grimaldi

Anita Maria Jimenez is a Chilean music teacher and pianist.

She was also an opponent of the regime of Gen Augusto Pinochet which took power in a military coup on 11 September 1973 and ruled Chile for 17 years.

Her opposition landed her in three of the 1,132 detention centres where the military junta detained almost 40,000 political prisoners and subjected them to physical and psychological torture.

Arrested in April 1975, when she was 23 years old, she spent a total of 18 months in prisons in the capital, Santiago.

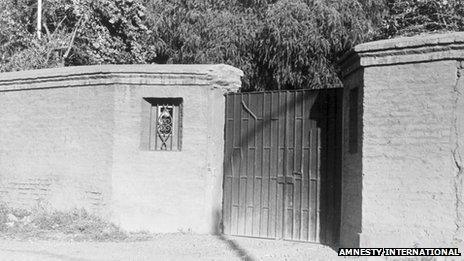

The first detention camp she was taken to was Villa Grimaldi, a notorious torture centre run by the secret police (DINA, later renamed CNI), where some of the harshest types of torture were inflicted and hundreds were killed and "disappeared".

Despite the regime of terror and precarious living conditions all inmates were subjected to, Ms Jimenez and her fellow prisoners managed to develop musical activities while in captivity.

But music was not just used by the prisoners. Their captors, too, used music as a form of punishment and a soundtrack to torture.

One of the episodes Ms Jimenez remembers most vividly from her time at Villa Grimaldi happened during a winter's night when a guard demanded she sing for the entertainment of DINA personnel.

Villa Grimaldi was one of the most notorious torture centres under military rule

She refused, despite the guard threatening to punish all the prisoners if she did not obey.

"Although I felt frightened, I decided that my small act of rebellion would be not to sing. Also, I thought I would not be able to," she told me.

But when the guard left briefly to get cigarettes, another detainee persuaded Ms Jimenez to sing, not to please the jailer but to comfort another prisoner, Cedomil Lausic, who, after a brutal torture session, was suffering in solitary confinement at some distance.

When the guard returned, Ms Jimenez was singing Zamba Para No Morir (a song made popular by Argentine singer Mercedes Sosa, whose music was banned by the Pinochet regime) at the top of her lungs, hoping the song would lend some strength to her fellow prisoner.

She was punished for her act of rebellion and had to spend the entire night in the rain. She later learned that her song was the last thing Mr Lausic heard before dying.

He was 28. His name is one of those listed on the Wall of Names, a memorial erected at the site where Villa Grimaldi stood.

Cedomil Lausic was among the many killed at Villa Grimaldi

The original buildings were demolished by the military in 1989 and the former torture centre is now a memorial park.

Ms Jimenez was later transferred to Tres Alamos, a detention camp for political prisoners in Santiago. There she ran a weekly music workshop for inmates, teaching guitar, recorder and singing.

Suddenly, after several months, the camp administration decided to forbid this activity, as well as the many other workshops organised by the inmates.

Ms Jimenez thinks the reason for this ban was that the authorities feared the prisoners were getting too organised.

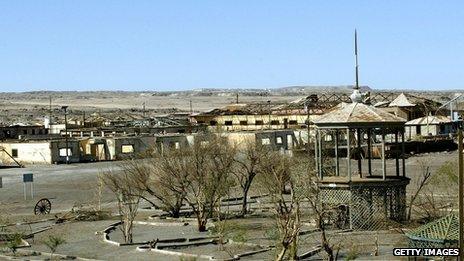

Across Chile, there were 1,132 detention camps, such as this one in Chacabuco

She convinced the authorities that having a choir of about 100 people would improve the camp's image, particularly as they were expecting an inspection by the human rights commission of the Organisation of American States.

The authorities agreed to the project, but not to the prisoners performing to the commission.

Revival

The choir rehearsed twice a week.

Many participants did not have any previous musical experience. They sang songs that were already part of the camp's repertoire. The most emblematic were Palabras para Julia and Candombe para Jose.

The choir lasted five months, until September 1976 when all but six prisoners were freed or exiled.

The mass release was widely seen as an attempt by the Pinochet regime to diminish international criticism of its human rights record.

Forty years on, a group of prisoners led by Ms Jimenez has revived the choir and will perform in an event commemorating the 40th anniversary of the coup, to be held at Villa Grimaldi.

Recruiting participants for the choir has been difficult, Ms Jimenez says.

"There are people who cannot be bothered, others smoked too much and lost their voices. Forty years have passed: those who are 80 now aren't able to stand and sing. They are tired, or ill."

Enduring legacy

Apart from the emotional challenge of making music in a place that brings back extremely painful memories, for Ms Jimenez there are additional physical difficulties.

She recently suffered a stroke and has become almost deaf.

But despite the memories Villa Grimaldi brings back, former political prisoners who have joined the choir look forward to singing at the event on 11 September.

Lucrecia Brito (3rd from left) and Carena Perez (right) say the choir is still relevant

Lucrecia Brito was detained at the age of 20 and was held for seven months in Villa Grimaldi, Tres Alamos and Cuatro Alamos detention centres.

For her, it is about remembering the past, "commemorating life despite torture, an homage to all those who went through Villa Grimaldi and other detention and torture centres".

For others, like Carena Perez, it is about the future.

Ms Perez, who spent five months in detention in 1975 in Villa Grimaldi and three other detention centres, says she sings for those who did not live through the events "because there are still people who do not know what happened, and singing is our way of denouncing it".

Dr Katia Chornik is a musicologist at the University of Manchester. Her article is based on research for the Leverhulme project: Sounds of Memory: Music and Political Captivity in Pinochet's Chile.