What is the secret to Mexico's cinematic success?

- Published

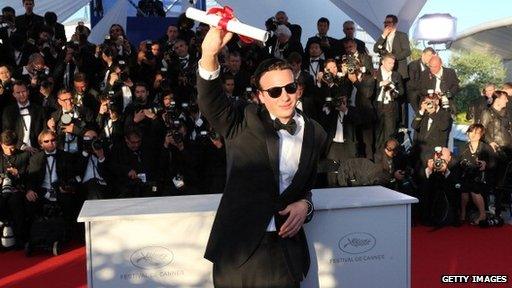

Amat Escalante was the second Mexican running to win Best Director award at Cannes

As the cinema-goers emerged, blinking and disorientated into the light, the overwhelming murmur was one of approval.

Handing back their plastic 3D glasses, they were the latest audience in Mexico City to enjoy the cinematic assault on the senses that is Gravity.

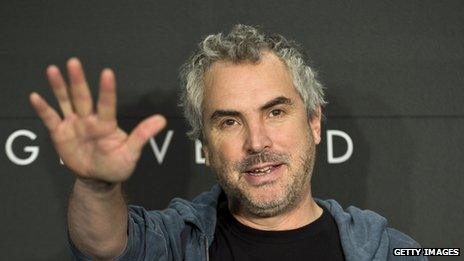

But as well as approval, there was also a certain pride among viewers here that this extraordinary piece of filmmaking - tipped for an Academy Award and prompting comparisons with legendary US film director Stanley Kubrick - was directed by a Mexican, Alfonso Cuaron.

"I'd put Gravity up there with the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema," gushed audience member Maria Esther Dominguez referring to the 1930s, 40s and 50s when Mexican films were considered among the best in the world.

Hyperbole aside, 2013 has been a hugely successful year for Mexican cinema.

For the second year running, the Best Director prize at the Cannes film festival went to another Mexican, Amat Escalante, for Heli, a powerful drama set in a drug war-ravaged region of rural Mexico.

Meanwhile, Mexican comedies Nosotros Los Nobles and Instructions Not Included have successively broken domestic box office records.

Cinema nights

Mexican cinema has been on the crest of a wave of success for over a decade now. And it is still thriving despite the challenges of a global recession and fierce competition for international funding.

What, then, is its secret?

"First and foremost, there has always been great, great talent in Mexico," says Daniela Michel, director of the 11th Morelia Film Festival held last month in the state capital of Michoacan.

"The institutions and film schools here work very well and they have supported interesting projects. There is a vibrancy and a great energy at the moment."

In particular, events such as the pop-up cinema nights in Mexico City called Ambulante have given a platform for young filmmakers to show their material on the big screen.

But beyond mere talent or institutional support, which is present in many other Latin American and European genres of film, there is something about the distinctly Mexican identity of the films being produced which seems to appeal to audiences.

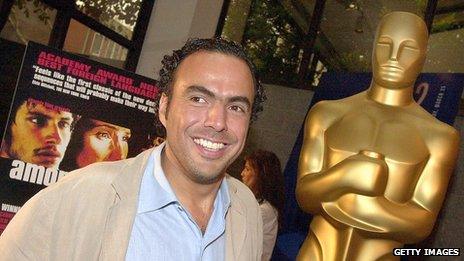

The new boom started, Ms Michel believes, around the time of Amores Perros, a gritty urban movie made in 2000 by Mexican director, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, which helped put Mexican cinema back on international screens after decades in the relative wilderness.

Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's film Amores Perros is widely held to have heralded the boom

In the intervening 13 years, the success of the industry has gathered pace. Mexican directors and producers regularly reap awards in festivals such as Cannes, Sundance and San Sebastian, and many - like the poster boys of Mexican film, Diego Luna and Gael Garcia Bernal - have broken through in Hollywood too.

Alfonso Cuaron is undoubtedly the stand-out Mexican director of the year. But his younger brother, Carlos Cuaron, also featured at the Morelia festival, showing his film Besos de Azucar.

Unlike Alfonso's high-budget Hollywood epic set in space, Carlos' film is a simple story of first love between two teenagers in Tepito, a rundown and corrupt neighbourhood of Mexico City.

"What I think is beautiful in Mexican cinema right now is its huge variety, and part of that variety is realism," Carlos Cuaron told the BBC after his film was played to an audience so large people were sitting on the steps and blocking the fire escapes to see it.

'Just do it' generation

"I love to create universal characters and work with universal themes in very specific contexts. In this case, not only Mexico City but the neighbourhood of Tepito. It's a very honest social portrait and I think that's why people in England or in the US get it."

Tepito is famous in Mexico for its market selling pirated goods. The two children in the film come from families tied up in that corrupt, often dangerous world.

"There was an American in the audience who'd been living in Mexico for some time and he was really touched," says Cuaron. "He loved the story and said it was the most faithful and honest portrait of Mexico he had ever seen. Well, that's a beautiful boost to my ego!"

Among the variety Cuaron refers to in Mexican cinema are advances in animation, with the first Mexican animated film in 3D, El Americano, being released this year, as well as a whole host of short films and documentaries from first-time directors and producers.

He says there is an element of fearlessness among young Mexican filmmakers, who are not waiting for a green light from a major studio.

"My generation was called the Crisis Generation. As kids, we had one crisis after another for 30 years! These young people don't care about any crisis. They just do it, and it's amazing."

Mexican director Alfonso Cuaron's film Gravity has won rave reviews

Given the international success of Escalante's Heli - which tells the story of a teenage girl falling in love with a young man being dragged into the drug world - one might expect films that evoke the country's drug violence to be the driving force behind the current boom in Mexican cinema.

In fact, says Morelia Festival director, Daniela Michel, nothing could be further from the truth.

"Mexican cinema doesn't prioritise the violence because Mexicans themselves don't prioritise the violence either," she says.

She believes that events like Morelia, held in one of the most dangerous states in Mexico, help to show the other face of the country - its cultural and artistic side, which so often gets lost amid the violent headlines.

It is an image many Mexicans would prefer to project.

- Published18 April 2013

- Published22 February 2012