Amazon gold workers fight to stay in their mine

- Published

Life as an unregistered gold miner

In the remarkable gold rush that gripped the Tapajos river basin after the metal was discovered there in 1958, tens of thousands of garimpeiros (prospectors) moved in.

While only a few got rich, most made a much better living than they would have done in rubber-tapping, fishing or subsistence agriculture.

Although the pickings have become sparser in recent years, many men are still at work in primitive, unregistered gold mines.

The discovery of vast gold reserves in the subsoil has put the small-scale prospectors at odds with big, modern mining companies.

The subsoil reserves are inaccessible to the artisanal mining methods of the garimpeiros, but multinational companies are keen to stake a claim on these untapped riches.

Eviction

The hamlet of Sao Jose on the Pacu river is at the centre of one such conflict between garimpeiros and mining company Ouro Roxo Participacoes.

A few years ago, Ouro Roxo Participacoes - part of the Canadian mining group Albrook Gold Corporation - registered mining rights over the subsoil in the Paxiuba mine, where garimpeiros still extract gold by the same age-old methods.

In March 2010, federal police and government officials arrived and ordered the garimpeiros to leave.

They did so, but only very reluctantly, arguing that their families had lived in the region for more than half a century, during which time they had acquired rights to the land.

Garimpeiro leader Jose Gilmar de Araujo says that since then, they have been trying hard to get their mining activities legalised, taking their request as far as the federal capital, Brasilia.

But, he says, "we're getting nowhere".

Mining life

Sao Jose is not as bustling as it once was but it remains a working currutela - as the gold mining villages are called.

The shops around the central square, which doubles up as a a football pitch, sell goods at inflated prices.

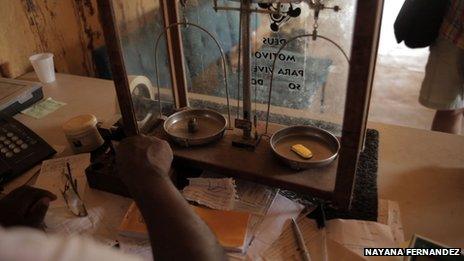

Shopkeepers charge up to $5 (£3) for a kilo of onions, using tiny scales to measure the payment in gold.

Shops accept gold nuggets as payment for goods

There are four brothels. During the week, bored women hang around the bar, often serving drinks.

But at the weekend, the brothels come to life.

Garimpeiros arrive from nearby mines, and, after getting their gold extracted over an open fire, spend their hard-earned cash.

In the early days, there was a lot of violence in Sao Jose, residents say.

"When I arrived here in 1986, someone was shot dead almost every day", brothel owner Ozimar Alves de Jesus recalls.

Sao Jose has become more peaceful since its violent early days

Today, the hamlet is a very tranquil place.

Drug-traffickers are asked to leave and the community association holds regular meetings to sort out any problems that may arise.

Prostitutes are accepted. There have been several cases of women who arrived to work in the brothels, married garimpeiros, and are now running successful businesses.

Game of chance

The garimpeiros mine the gold by first digging vertical mineshafts, from which galerias, or horizontal tunnels, branch off.

It is hard work and entirely unpredictable which galerias will yield rich pickings.

For many, this is where the lure of the garimpeiro life lies. "It's a bit like going to a casino", one miner confesses as he explain how garimpeiros will return to the mines time and time again in the hope of finding a rich vein.

Their main problem lies with uncertainty about the future of the mine itself - and the power the big mining companies have.

"A big company arrives and doors open for them," prospector Jose de Alencar says.

"They can get their activities regularised overnight. It seems as if there is one law for the big companies and another for us."

Occupation

After their 2010 eviction, the garimpeiros tried for three years to get permission to return to the Paxiuba mine.

Garimpeiros work the mines in age-old fashion, digging basic tunnels

On 12 June 2013, they took matters into their own hands and reoccupied it.

Mr Gilmar de Araujo says they were driven by "economic necessity".

"We've put all our money into this mine. We'll be ruined if we can't produce gold."

They are still there, mining. Meanwhile, Ouro Roxo Participacoes is losing money and is angry.

"If they go on mining, they will make the whole project unviable for us by the damage they do," says Dirceu Santos Frederico Sobrinho, a Brazilian shareholder in the company.

"The garimpeiros don't develop. They are stuck in a culture of poverty, prostitution, drugs", he adds.

According to the lawyer for the garimpeiros, Antonio Joao Brito Alves, the conflict is escalating.

He says that Mr Santos Federico told him he and his family would "suffer the consequences" if he did not give up the Paxiuba case.

The garimpeiros say they have poured all their money into the mine

Mr Santos Federico vehemently denies having threatened Mr Brito Alves.

The ramifications of this conflict could have wider implications.

If the garimpeiros win, or are given hefty compensation for leaving the mine, many other gold mining communities are likely to come forward with the same demand.

The small hamlet of Sao Jose has become an unlikely test case for a wider battle for garimpeiros' rights.