Colombian port city terrorised by criminal gangs

- Published

Residents of Buenaventura have been living in fear as gruesome killings mount

Standing by Colombia's Pacific shoreline a woman who prefers to remain nameless tells me about the horror that her hometown is experiencing.

After she has made sure no-one can overhear us, she tells me about the realities of living in Buenaventura, Colombia's biggest Pacific port.

"Nowadays you cannot move freely between neighbourhoods," she says.

"If I tried to go over there," she says nodding in the direction of a nearby neighbourhood, "they would hit me, or disappear me, or kill me."

She says sometimes people in the city's oldest neighbourhood of San Jose, also knows as Sanyu, just disappear.

Venturing into a neighbourhood not your own can prove lethal in Buenaventura

"They capture them, take them away, chop them to pieces, put them in bags and drop them in the sea," she explains.

"Sometimes you come across an arm, different body parts, a head," she adds.

Return to criminality

The "they" she is referring to are members of Colombia's notorious criminal gangs.

Almost 20,000 people fled Buenaventura last year

The gangs have been around for years, their numbers swelled by former right-wing paramilitaries who demobilised as part of a peace process but then returned to a life of criminality.

But the torture, disappearances and dismemberments of victims which is currently plaguing Buenaventura is a recent development.

The escalation of violence is blamed on a turf war between two rival gangs - the Urabenos and La Empresa - for this strategic spot for the drugs trade.

According to a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, external released on Thursday, entire neighbourhoods are dominated by powerful "paramilitary successor groups" which restrict residents' movements, recruit their children, extort their businesses, and routinely engage in horrific acts of violence against anyone who defies their will.

"In several neighbourhoods, residents report the existence of casas de pique - or 'chop-up houses' - where the groups slaughter their victims," reads the document.

The HRW researchers say that several residents told them they had heard people scream and plead for mercy as they were being dismembered alive.

The fear is that these are not isolated cases. Between January 2010 and December 2013 more than 150 disappearances were reported in Buenaventura; twice as many as in any other Colombian municipality.

But with many victims' relatives too scared to speak out, the actual figure could be much higher.

Close enemies

The Sanyu resident says no one can be trusted. "Even eight-year-old kids are involved in the violence. You believe they cannot be evil, but they're evil. You might be talking to your enemy," she explains.

Evil is a word also used by Buenaventura's bishop, the Right Reverend Hernan Epalza. "It is as if all the evil of Colombia has gathered here in Buenaventura," he says.

"Disappearing and dismembering people? I cannot think anything worse," he tells the BBC.

Bishop Epalza thinks poverty and lack of opportunities are contributing to the violence

Buenaventura's police commander Col Jose Correa thinks these extreme methods are used like brutal calling cards.

He says his force has managed to capture or kill a number of criminal leaders and the resulting vacuum has further fanned the violence as lower-ranking criminals use all the brutality they can to assert their authority.

But he says he is confident the security forces will soon have the situation under control.

Bishop Epalza, however, thinks a more integral approach is needed to combat the poverty and lack of opportunities which he believes feed the extreme violence.

He says the poorest inhabitants are being further marginalised by the increasing importance of the port city.

More than half of the country's cargo already goes through Buenaventura and the flow is set to increase as Colombia looks for new markets in Asia and tries to consolidate its links with Mexico, Peru and Chile.

Buenaventura is Colombia's largest Pacific port

He says the violence is forcing those at the bottom of the ladder to sell up and leave, something he says may be a desirable effect for some.

"We have to asked ourselves: who's behind all of this, who's fostering all this?" he asks.

Pushed out

Back in Sanyu, the local residents say it does feel as if much of the violence is designed to push them out.

Their neighbourhood is one of Buenaventura's poorest.

Currently, it is nothing more than a collection of derelict wooden huts built upon wooden pillars on land reclaimed from the sea by the descendants of African slaves which first settled here almost five centuries ago.

Poor residents of Buenaventura often live in shacks built on wooden stilts

But its proximity to the water makes it of great strategic value for those intent on smuggling drugs and weapons.

And its potential worth could be huge if the city decides to expand the port to this area.

Already, residents have started to leave.

In 2013, 19,000 people were forced to flee their homes in Buenaventura, ensuring the port city a third place in the list of Colombian cities where forced displacement is highest.

Turning tide

But there have been signs that the tide might be turning.

Last week people took to the streets to protest against the violence.

President Juan Manuel Santos visited the city a few days later and set up a task force to deal with the crisis, promising more security and huge social investments.

President Santos has promised extra security for the port city

There seems to be some hope among residents who before only felt fear.

But according to HRW executive for the Americas Jose Miguel Vivanco, Buenaventura is just an "extreme example of a reality that exists in different regions of Colombia".

He told the BBC that the criminal gangs which sprang from the demobilised right-wing paramilitary groups should be a sobering reminder of the importance of a proper demilitarisation of former combatants.

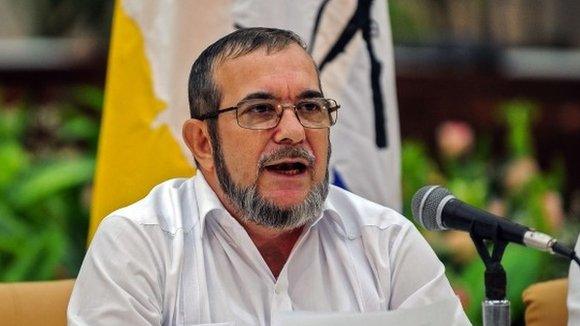

On Thursday, government negotiators will begin the 22nd round of peace talks with the country's largest rebel group, the left-wing Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc).

So far, they have taken over a year to agree on two items of their six-point agenda.

But as the negotiations continue, the hope is that the lessons learned from the flawed demobilisations of the past will mean that Colombia's dreams for the future will not turn into the stuff of nightmare as it did in Buenaventura.

- Published3 October 2013

- Published24 September 2015

- Published29 April 2013