What is at stake in the Colombian peace process?

- Published

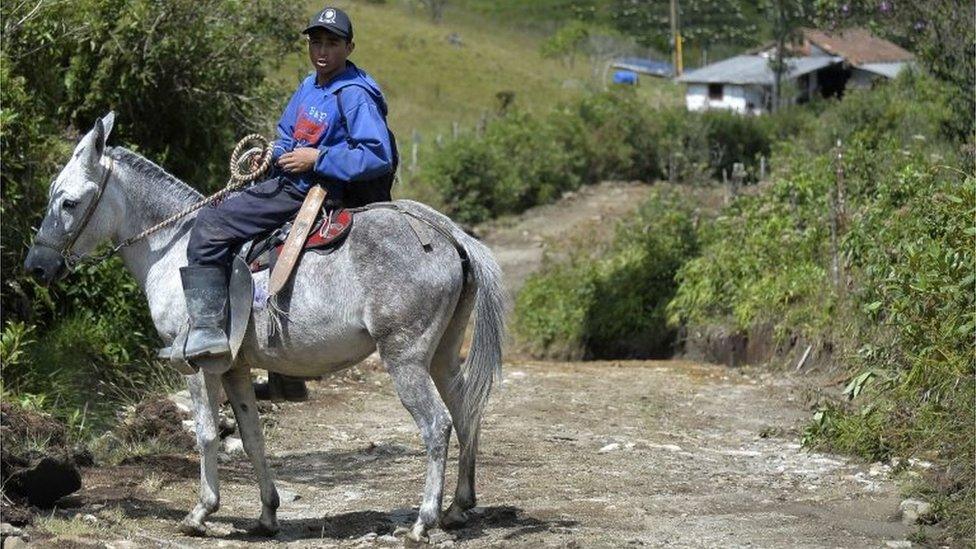

The peace talks started in Havana in November 2012

The Colombian government and the country's largest left-wing rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), are trying to end more than five decades of armed conflict.

The two sides began formal peace talks in November 2012 in the Cuban capital, Havana.

Since then, they have reached agreement on four key topics and have set themselves a deadline of 23 March 2016 to sign a final document.

What is at stake?

More than 220,000 people are estimated to have been killed in the 51-year-conflict

According to a report by Colombia's National Centre for Historical Memory (in Spanish), external, more than 220,000 people have been killed in the armed conflict - 80% of them civilians.

More than seven million people have registered with the government's Victim's Unit. The vast majority have been internally displaced by the violence, but many have also been kidnapped, threatened, injured by landmines or forcibly disappeared.

However, not all of the violence is caused by Farc insurgents.

The National Centre for Historical Memory found that more than half of the massacres in the past three decades had been carried out by right-wing paramilitaries, originally created to combat the Farc.

Criminal gangs vying for control of Colombia's lucrative cocaine production have also become an increasing threat.

The hope is that a permanent settlement with the Farc will allow the security forces to concentrate on combating that threat and protecting the civilian population rather than fighting a protracted battle with Farc rebels.

What has been achieved so far?

The rebels have agreed to lay down arms within 60 days of a final agreement being signed

Agreement has been reached on four broad points, but under the terms of the negotiations, they will not be acted upon until a final peace deal has been signed.

They are:

Land reform: economic and social development of rural areas and provision of land to poor farmers

Political participation of rebels once a peace deal is reached

Illegal drugs trade (one of the main sources of funding for the Farc): all illicit drug production will be eliminated

Transitional justice: amnesty for combatants, excluding those who have committed the most serious crimes

What are the next steps?

Colombians from all walks of life will be asked to vote for or against the peace deal in a referendum

The teams are still working on many details but their leaders have set a deadline of 23 March 2016 for a final document to be signed.

A final deal will be put to the people of Colombia in a referendum.

While many Colombians have welcomed the progress made, there are also those who doubt that the rebels' motives are genuine.

Some victims have also been critical of the fact that the guerrilla leaders are unlikely to go to jail.

Under the deal on transitional justice reached in September, only those who refuse to own up to crimes committed will be sent to ordinary prisons while the others will undergo "alternative forms" of punishment.

What are the stumbling blocks?

It will take years to remove all the landmines which were planted during the conflict

There are powerful voices in Colombia questioning the peace process and criticising the government's "willingness to make concessions" to the rebels.

The most vocal critic is former president Alvaro Uribe, who argues the rebels are "getting away with murder", referring to the amnesty offer for rebels willing to confess their crimes.

Re-integrating thousands of rebels will also be costly. The re-integration process takes years, with former combatants offered psychological help and vocational training,

Other key points agreed at the talks will also not come cheap, such as land reform and replacing illegal crops with legal ones.

All of these changes are unlikely to happen unless the Colombian people in general decide to back them.

It is they who have to vote for the final peace agreement in a referendum and they who ultimately have to drive the reforms agreed in the deal.

- Published31 October 2014

- Published9 April 2014

- Published3 October 2013