Venezuela's fading dreams

- Published

Venezuelans face long queues for even the most basic items

"I'm really sorry Sir, but we have no soap in the rooms. It's because of the situation here, you see."

So began my unscheduled night's stay in the Venezuelan border town of Pinal.

The hostel owner was deeply apologetic and resigned to his predicament.

They have become used to shortages here. Soap, toilet paper, coffee, sugar - all absent or in short supply as a result of Venezuela's worsening economic crisis.

Thanks to its vast oil wealth, this country should be one of the richest nations on the planet. So it is somewhat perplexing that basic goods are routinely not available on the shelves of Pinal, or the capital Caracas for that matter.

Doctors took part in an anti-government rally in March complaining about a shortage of medical supplies

Strict currency controls, economic mismanagement, corruption and inflation are all partly causes of the problem.

The government of Nicolas Maduro blames the shortages on "speculators", "bourgeoisie business leaders" and the United States. Many of his supporters agree with him.

I had ended up in Pinal after a longer than expected drive from San Cristobal, the university town where the current wave of protests began at the start of February.

Seed of discontent

Back then, a student demonstration against rising crime, which often goes unpunished, was brutally put down by the local military police.

The detention and allegations of mistreatment of students sparked further protests across the country.

Thousands of troops were flown in to this remote part of the country to restore order and clean up the barricades.

The army and police units have retaken control of San Cristobal, for now.

Some of the student leaders are in police custody. Others we spoke to have gone on the run and say they will continue their protests against corruption and violence.

Police are out in force to try to control unrest

But their numbers are dwindling.

Night-time battles

Just how popular, or otherwise, the anti-government protests are is difficult to know.

The barricades that radical students put up around Caracas do not endear them to local residents, but many in Venezuelan society still support their aims.

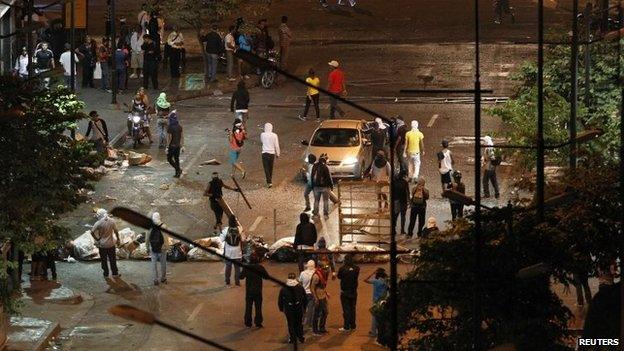

Barricades have become a common feature of the anti-government protests

Under the persuasion of regional foreign minsters, opposition leaders and government officials are now preparing to hold formal talks to try to stop the wave of protests that spread from San Cristobal to Caracas and other Venezuelan cities.

Still, there are battles most nights between government supporters and opponents in Caracas.

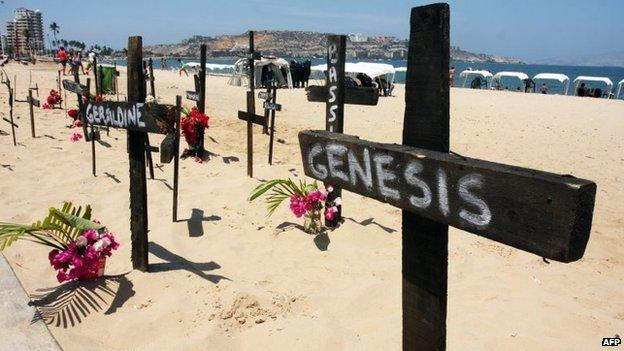

Since the clashes began, almost 40 people have been killed and hundreds injured as both sides fire live ammunition.

Clashes between anti-government protesters and the security forces are a nightly occurrence in some areas

Members of the security forces and protesters regularly face off on the streets of Caracas and other cities

Thirty-nine people have died in protest-related violence since the unrest started

Subsidised petrol is used to light Molotov cocktails

The petrol that has often proved more of a curse than a blessing for Venezuela is now used by angry young students to fuel their Molotov cocktails.

Many Caracas residents say their lives have been put on hold by the protests, which flare up most nights - a situation they say is completely unsustainable.

By day, the longer-running economic difficulties become apparent as long queues form outside government-owned supermarkets for basic goods.

"I've queued more than three hours for milk, flour and bread, but there's no sugar," one visibly frustrated man told me as the queue behind him snaked slowly around the hill near Petare, a sprawling working-class suburb of the capital.

Another overwhelming concern for Venezuelans are skyrocketing crime rates.

Murder rates here are now among the highest in the world and most violent crime goes unresolved and unpunished.

Ultimate price

Some have paid a high price for protesting against rising crime rates.

Carmen Gonzalez (right) says her son was killed by the security forces

In the yard of a modest house in one of San Cristobal's quieter neighbourhoods, a young dog paces back and forth, waiting for his owner to come home.

Inside, Carmen Gonzalez holds the blood-stained glasses that her son Jimmy Vargas was wearing when he died.

As she shows me pictures of his body, stored on her mobile phone, she insists he was shot by the army while protesting.

The death of Jimmy Vargas further fuelled the protests in his hometown of San Cristobal

The prosecutor's office ruled his death was an accident, saying that he fell to his death after losing his balance trying to descend from a roof he had climbed.

"He loved his country but said he couldn't live in a dictatorship and felt he had to do something about it," his mother recalls. "The government will pay for what they did to my son."

Divided opposition

Opposition to the government of Nicolas Maduro is divided between those who call for direct action and those moderates who see dialogue with the government as the way forward.

At a rally in downtown Caracas, speech after speech demands the release of the jailed opposition leader, Leopoldo Lopez.

Leopoldo Lopez was arrested in February and has been charged with inciting violence

Speakers also call for the downfall of what they say is an increasingly authoritarian, even dictatorial regime.

There is no doubt that, at this point in the crisis, the government is unpopular with many.

It has also often been accused of blatantly politicising what should be independent offices of state or of using government decrees to bypass parliament.

But this government's trump card is that it is democratically elected.

After a press conference to update how police investigations into the troubles are progressing, I interviewed Venezuela's Attorney General, Luisa Ortega.

She is one of those very officials, a senior public servant, whose office has been accused of acting in a blatantly partisan manner.

It is a charge that Ms Ortega rejects. She alleges that Venezuela's enemies at home and abroad are deliberately undermining the system and the government.

"These calls for the overthrow of the government are hostile and totally unacceptable," she tells me.

"In Venezuela we have democratic checks and mechanisms in place to change our government if that's what people want."

Core of support

The government draws its support from working-class suburbs like the 23 of January where Hugo Chavez spent millions of dollars on social projects.

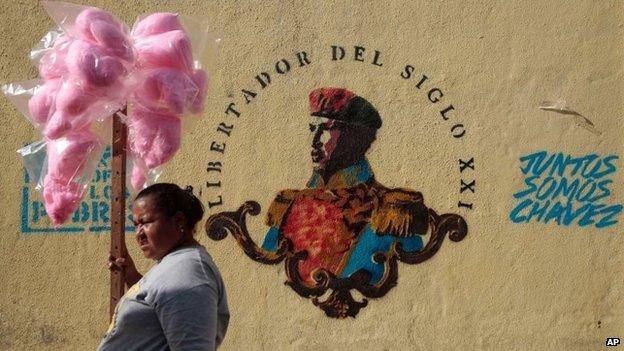

The former president died from cancer just over a year ago but his image is painted on buildings overlooking the city below.

Murals of former President Chavez abound in the working-class districts of Caracas

Devotees pay homage at a shrine to "El Comandante", who is still revered here as the man who finally shared some of the country's oil wealth with the working classes, breaking the shackles imposed by an economic elite, and who encouraged these people to become activists.

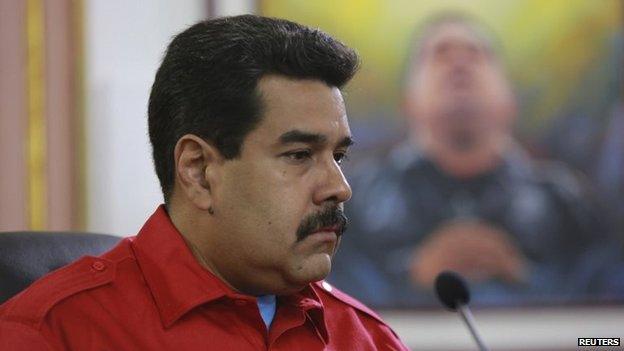

Nicolas Maduro was Mr Chavez's chosen successor and has tried to continue in the same vein. But despite his almost daily appearances on pro-government media outlets, Nicolas Maduro is not Hugo Chavez.

Nicolas Maduro often appears in front of picture of Hugo Chavez to show his allegiance to the late leader

Even among his supporters, there are those who say he does not have the same charisma or authority to unite the nation through these difficult times.

While there may now be some hope that the government and some members of the opposition will engage in dialogue, the language from both sides has been worryingly bellicose and divisive.

In a country still deeply divided by class and ideology, many feel that Hugo Chavez's dream of a socialist utopia in Venezuela may be fading.

- Published27 March 2014

- Published7 March 2014

- Published16 January 2014

- Published29 December 2013