Easter Island's lone honorary consul

- Published

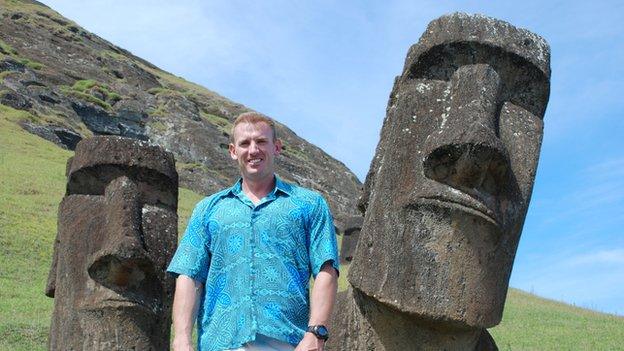

James Grant-Peterkin is one of the few foreigners to have learned Rapa Nui

Imagine a job in which you are 3,600km (2,250 miles) from your boss and 14,000km from head office in London.

Sound appealing? Then maybe "honorary consul to Easter Island" is the job for you.

It is a position that James Grant-Peterkin has held for five years. He is the British government's representative on this remote Chilean outpost in the South Pacific.

His position is unique. Britain is the only country in the world with consular representation on Easter Island.

If the islanders were ever to throw a diplomatic party, Mr Grant-Peterkin would be the only guest.

Self-appointed

"I basically appointed myself," says the 36-year old Scot, who has lived on the island for 12 years and is among only a handful of foreigners anywhere in the world who speak Rapa Nui, the local language.

Mr Grant-Peterkin also works as a tour guide

"I realised there was no diplomatic representation here from any country and we were getting quite a few problems with tourists losing passports and having medical emergencies.

"So I went to the British embassy in Santiago and asked them if they'd be interested in having an honorary consul here.

"They were fairly surprised but in the end they thought it was a great idea."

Mr Grant-Peterkin's is not a full-time job. He works mostly as a tour operator and has written a guide book to the island, which he first visited in 1996.

But if ever a British visitor gets into trouble, he is here to help out.

"We've had a few people who drink more than they should, who lose passports, who have motorcycle accidents, so I spend quite a lot of time at the hospital, helping them with the paperwork," he says.

His role has proved so useful that other European countries have turned to him for consular assistance.

"I actually spend much more of my time dealing with nationals from other countries than I do with Brits," he says.

In 2008, for example, a Finnish tourist caused uproar on the island chipping an ear off one of the world-famous stone statues, the Moai.

Easter Island is famous for its Moai, monolithic human heads and figures carved from rock

He was arrested and taken to court, and Mr Grant-Peterkin was called in to help out with translation.

It was that case that prompted him to approach the British embassy in Santiago and offer himself as honorary consul.

"We've had a few cases of visitors who come here and damage the statues," he says. "I've had to help get a few of them out of the island jail."

Modest digs

With the number of visitors to Easter Island growing, the honorary consul's workload is likely to increase.

Nearly 80,000 tourists came to the island last year, about 3,000 of them from Britain.

The job does not come with a grand ambassadorial residence. Mr Grant-Peterkin runs the consulate from his wooden bungalow on the edge of the island's only town, Hanga Roa.

But he does at least have a brass plaque on the wall of the bungalow to show that it is the consulate, and his car, with a big British coat of arms on the door, is a familiar sight on Hanga Roa's streets.

Mr Grant-Peterkin's residence may be humble, but he does have official signs on his car and door

"The islanders are very welcoming once they see you're here for the right reasons," he says. "I made a big effort to learn Rapa Nui and I think that helps enormously in terms of acceptance."

For now, Mr Grant-Peterkin has no plans to move on, so if you're thinking of applying for his job you might have to wait a while.

"This is a very difficult place to leave once you've been here for a long time," he says. "I'm not sure I'd ever fit back in to the UK now."

- Published18 April 2014

- Published7 August 2012

- Published4 December 2010