Guantanamo Bay a thorn in Cuba's side

- Published

Fishermen still go about their traditional business in Guantanamo Bay

Guantanamo Bay is tranquil and picturesque on the Cuban side of the watchtowers.

Fishermen land crates of blue-clawed crabs from wooden boats and a woman browses a newspaper beneath a palm tree as children splash in the sea, escaping the baking sun.

But clearly visible behind them is the perimeter of the US naval base that has occupied a substantial chunk of eastern Cuba for well over a century.

For the rest of the world, the controversy over Guantanamo Bay lies in its notorious US detention facility used for terror suspects.

Despite Guantanamo Bay's tranquillity, the presence of the US naval base nearby is an irritant to Cuba

Controversial presence

But for Communist Cuba, the controversy stems from the very presence of the Americans here.

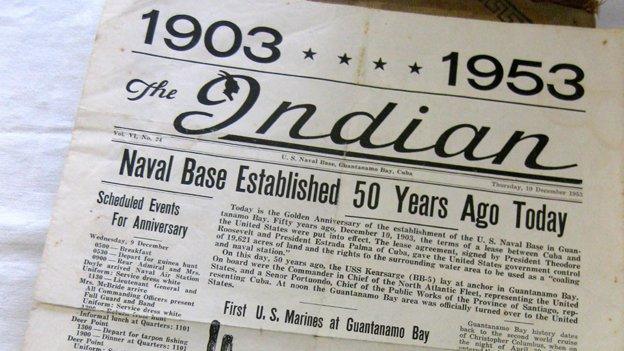

The land around the mouth of Guantanamo Bay was first leased to the US for a naval base in 1903.

The US naval base was established in Guantanamo Bay more than a century ago

After the 1959 revolution, Fidel Castro refused to accept the Americans' annual rent cheque of just $4,000 (£2,350).

He denounced the base as illegal, arguing that Cuba had been compelled to accept it as a condition of independence.

But the treaty can only be revoked if both signatories agree.

Radio silence

The bay was far less peaceful in those post-revolutionary years.

Fishermen say the best catch is in the US zone

Fishing boats initially passed through US-controlled waters to the open sea but were restricted to the inner section after a Cuban was shot and killed.

"The best catch is in their zone," insists Alexander Perez, pointing at the deeper waters around the US base, now off-limits to Cubans.

"We're just waiting, praying, for the Americans to leave," the fisherman adds.

A street back from the waterfront, Soviet-style housing blocks are daubed with revolutionary slogans in sun-faded paint.

Workers sit stitching wilting flowers into tiny bouquets, with a radio playing beside them.

Cuban state media is the only choice these days but residents used to pick up programming from the US base.

"People liked the sport especially," Javier recalls. "But we don't get anything anymore. It seems the signal's been blocked."

Sarah Rainsford meets residents of Guantanamo Bay

This place feels cut off in other ways, too.

Caimanera is the closest town to the US base and visitors need a special permit to pass Cuban checkpoints at its entrance.

The result is little tourism, meaning minimal outside influence or cash.

The only hotel appears empty and there is no sign of the small, privately run businesses now common elsewhere.

Residents get extra meat and milk rations to compensate for the restrictions and to keep them loyal, cheek-by-jowl with Cuba's ideological enemy.

At a state-run children's club, pensioners dance salsa among cartoon wall paintings and one woman proclaims Caimanera "the first line of defence against imperialism".

Some residents say the town is "the first line of defence against imperialism"

The bay once attracted less "revolutionary" Cubans trying to flee the island on rickety rafts.

But in 1995 the government completed a barrier to prevent them reaching the US base and to "prevent incursions" from the other side.

"There are very few cases now, only people tricked by those who say it's easy," says Danilo Rodriguez, the boss of a state-run fish company.

Two-way traffic

But there was always some traffic between the two sides.

Over the years, thousands of Cubans were employed on the US base. British West Indians also came seeking work and settled.

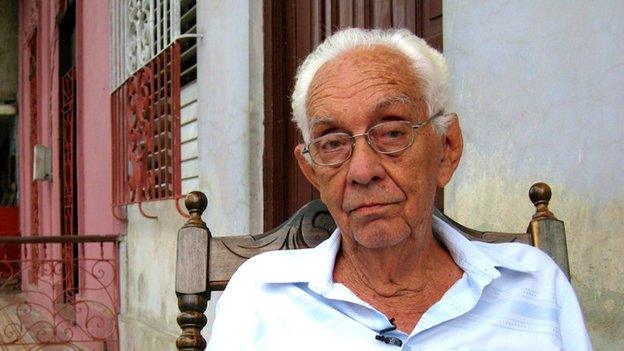

The US stopped hiring once Cuba turned communist in 1959, but many of those who were still employed at the time stayed on and were rewarded with substantial US pensions on retirement.

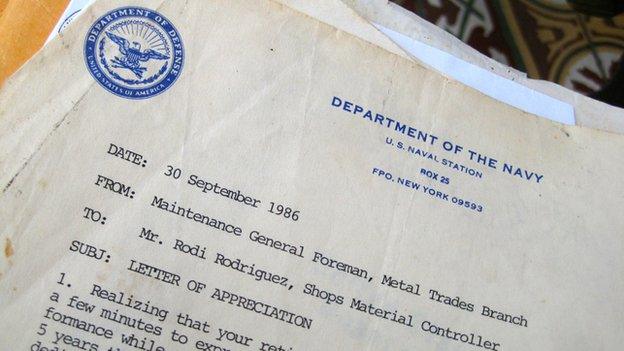

"I go to the gate and collect the money for the rest [of the pensioners] and bring it to Guantanamo," Rodi Rodriguez explains in the West Indian-accented English he picked up over almost four decades working alongside Jamaicans.

The onetime shop material controller, as his job title went, still has certificates of merit from the base complete with a US Department of Defense stamp.

"I had no problem," he says of his American bosses, and describes delivering wads of US dollars to a handful of surviving pensioners and workers' widows each month.

Rodi Rodriguez regularly goes to the base to pick up his pension payments

Mr Rodriguez worked on the US naval base for more than 30 years

It is not the only interaction across the lines.

The US and Cuba cut diplomatic ties in the 1960s but since the mid-1990s military delegations have met each month in Guantanamo without fanfare.

They even conduct joint drills for natural disasters.

'Assassination plot'

Before the revolution, contact was far greater.

Guantanamo was once full of American-named clubs, hotels and bars. City historian Jose Sanchez believes there were more English speakers here than anywhere else in Cuba.

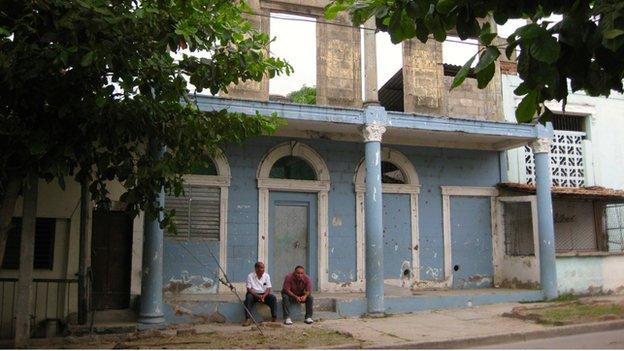

In the 1930s, the military base was expanded, providing a boom for local businesses - including prostitution.

"This was the biggest brothel in the Caribbean," Mr Sanchez laments, touring the former red-light district. He points out ramshackle wooden houses, divided into rooms for hourly use by US marines.

There is only a shell left of what used to be the brothel in Guantanamo

Cuba says that after the revolution, the base changed from a moral threat to a security risk.

"There were assassinations: a border guard, a fisherman, workers. Most aggressions launched in this region were planned at the US base," argues Mr Sanchez.

"There was even a plot to kill Raul Castro, and the arms and men came from there," he claims.

Irritant

Any direct danger has long since subsided but the continued US presence remains an irritant to many Cubans.

The naval base is a commanding presence in the bay

"We're spending a lot of money protecting our border that we could use to improve life here," Mr Rodriguez argues.

But there is little hope here of that changing soon.

US President Barack Obama "talks about closing the prison at Guantanamo", Mr Sanchez points out.

"But we've seen no sign he plans to close the naval base, and give the land back to Cuba."

- Published24 February 2014

- Published30 April 2013

- Published29 August 2023