Mexico police reform: How might it work?

- Published

Police stand guard at a Mass for the dead students in Iguala

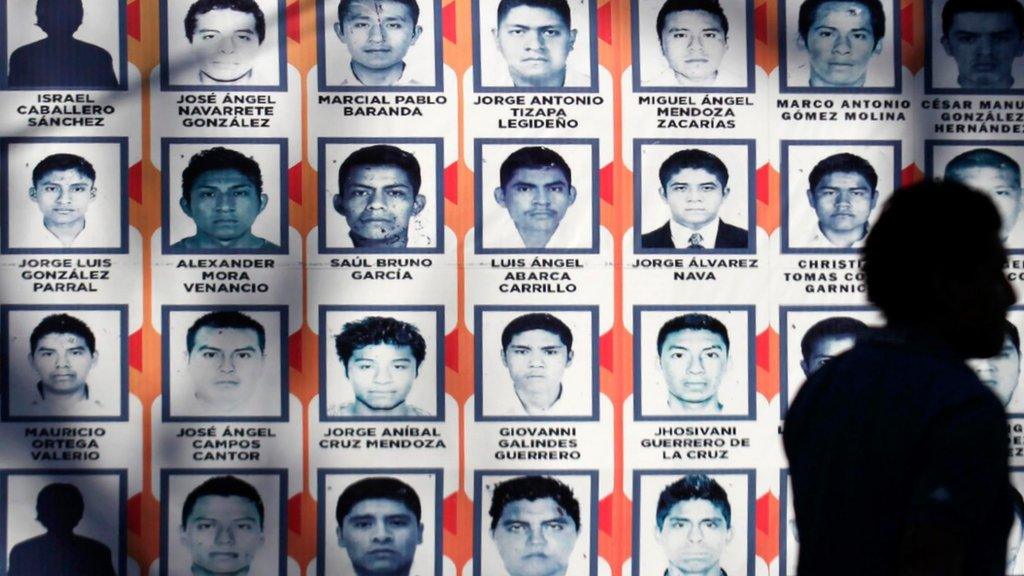

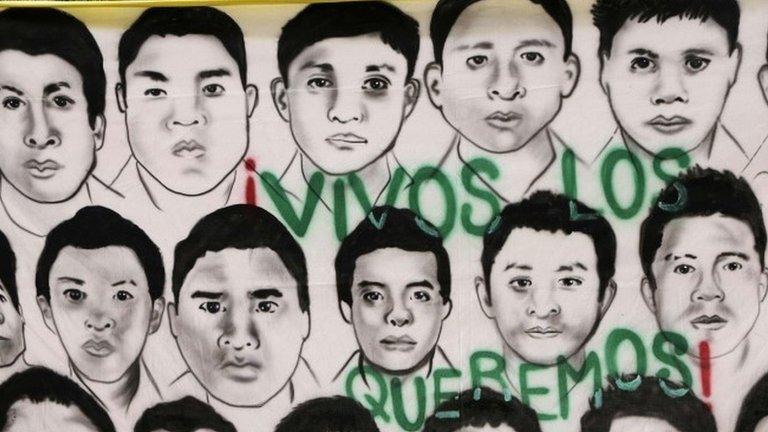

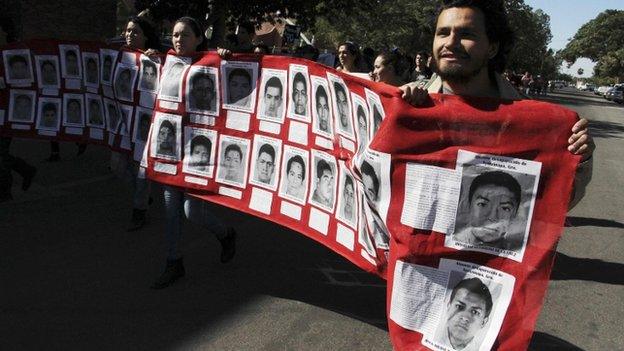

The Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto has unveiled a plan to reform the police, two months after they were implicated in a mass abduction in the town of Iguala which ended in the disappearance of 43 students. The attorney general's office says gang members confessed to murdering them.

Mr Pena Nieto hopes this plan will mark a turning point in the crisis. "After Iguala, Mexico should change," he said.

His supporters believe the 10-point plan will tackle the ingrained problems in policing and justice in the country, but opponents say the proposals fail to tackle the levels of corruption and impunity that allowed the disappearances to happen in the first place.

Here we look at five key proposals and some of the issues around them.

1. Replace the country's 1,800 municipal police forces with state-level forces

Presidential spokesman Eduardo Sanchez says this will ensure Mexicans will have "well-trained, well-equipped police capable of carrying out their duties efficiently". He cites the example of the state of Nuevo Leon, where a recent purge of municipal police forces produced "extraordinary results".

Recent attempts at purging local police forces, such as in the drug war-ravaged state of Coahuila, have failed but he says that the new measure will mean reforms are underpinned by federal law and "won't depend on the good will of individual governors or mayors".

Asked about the fate of existing municipal police officers, Mr Sanchez said there will be a purge but that "any citizen who meets the requirements of these (state-level) police units will be eligible to join."

Alejandro Hope, a drugs war analyst based in Mexico City, questions the value of applying what happened in Nuevo Leon to the rest of the country. He says the state has not been able to find enough new police to be an effective force.

2. Give the central government powers to dissolve local governments allegedly infiltrated by drug cartels

Eduardo Sanchez says the proposal is based on an Italian measure, enacted when there are "solid indications that the mayor or the local government is linked with organised crime". Some are already questioning the wisdom of copying on an Italian law, when the country has had Mafia problems for decades.

In addition, there are concerns that it is "another example of the centralisation of power", says Alejandro Ramos from the Centre for Human Rights in Guerrero

Mr Ramos, who has been working closely with the families of the 43 disappeared students, says he is wary any move that might increase the power of the presidency.

Alejandro Hope says that there are laws already to dissolve local authorities that the attorney general considers have been "compromised" by the cartels, but that the political will to do so has always been lacking.

3. Give national identity numbers to all Mexicans

Mexicans already have citizenship cards, so the proposal is for a new system that will include more information about physical appearance, and therefore be harder to counterfeit. The proposal is also to create some form of a national database. Government spokesman Eduardo Sanchez says the plan will "provide the certainty that Mexico has a register of its entire population".

Critics say the plan will add a new layer of bureaucracy to a country already deeply entrenched in government paperwork, but Mr Hope thinks the plan is a good idea.

"There could be some practical difficulties, as we already have a national identity number, but the key is to link legal identity to physical identity," he says.

4. Boost federal security forces in key areas

There are already around 10,000 members of the federal security forces in Guerrero and thousands more have been deployed to the three other troubled states: Michoacan, Jalisco and Tamaulipas. The government says more reinforcements are needed.

The idea assumes, of course, that the federal forces are trustworthy. Alejandro Ramos is far from convinced: "It's not just the municipal [police] forces who are 'contaminated'. All the police forces in Mexico are affected."

5. A national emergency hotline

There is no single number in Mexico to call in an emergency. Each state has its own number for key emergency services.

Few would argue against the creation of a single number around which all emergency services could coalesce, but representatives of the disappeared 43 students say that in today's Mexico, even a phone call is a question of trust.

"A national emergency number would be useful," says Alejando Ramos, "but at the moment civil society just wouldn't believe it. We know that the people who'd attend your emergency are the same police that are linked to organised crime."

- Published27 November 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published13 November 2014

- Published8 November 2014

- Published7 November 2014