Mexico missing students fury rocks President Pena Nieto

- Published

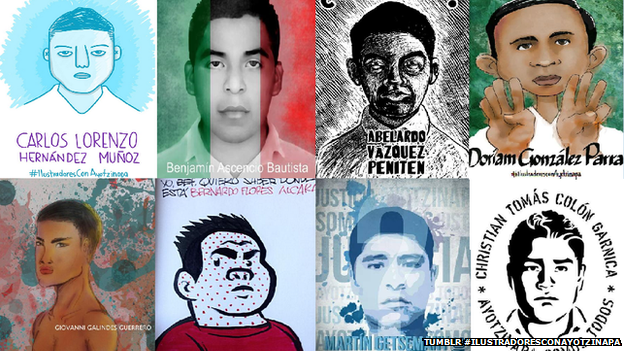

The case of the missing students has sparked widespread outrage

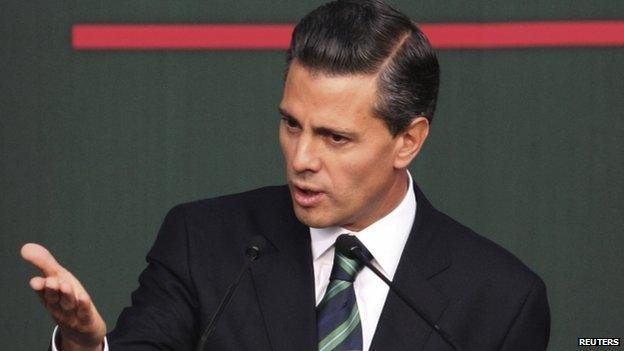

As Enrique Pena Nieto reached his second year in office, he might well have reflected on how quickly the narrative of a presidency can change.

In February, his airbrushed photograph graced the front cover of Time magazine with the much derided headline "Saving Mexico" emblazoned underneath.

Mr Pena Nieto had "passed the most ambitious package of social, political and economic reforms in memory", the publication, external said, adding that "alarms are being replaced with applause" in the country.

Now any applause for Mr Pena Nieto by the political and business elite has been drowned out by the near-constant calls for him to step down.

His anniversary, on 1 December, was marked by Molotov cocktails, broken windows and protesters clashing with the police in Mexico City.

The chain of events, external that sparked the crisis began on the night of 26 September.

Amid a protest in the town of Iguala, police fired on unarmed student teachers, killing six people.

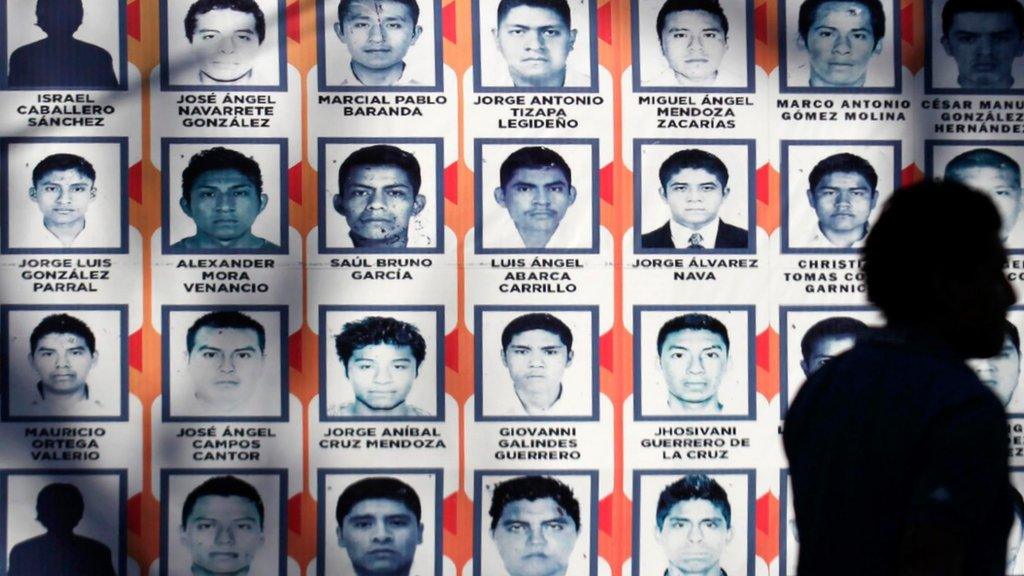

The officers then rounded up and abducted 43 students, who are now feared murdered.

The brutality with which the attorney general's office says they were killed by drug cartel members was ruthless, even by Mexican standards.

They had been trussed up, thrown on to police trucks and taken to the nearby town of Cocula, the attorney general said.

About 15 had died from asphyxiation en route.

And, once in Cocula, the students had been handed over by the police to members of the Guerreros Unidos cartel, who had shot the remaining youths in the head before burning their bodies in a vast funeral pyre and dumping the charred remains in a river.

Search continues

The motivation for the killings, the attorney general's office says, was that the students' protest in the town was disrupting plans the mayor's wife had for a political rally the following morning.

It is a version of events the families of the missing young people refuse to accept.

"We're going to keep looking for them," Clemente Rodriguez, father of 19-year-old Christian, told the crowd at the protest earlier this week.

Enrique Pena Nieto faces calls to stand down

"We're going to find them because it's been more than two months and we don't know anything about our children."

Clemente's wife, Maria Telumbre, is also unconvinced by the government's grisly tale of how their sons were slaughtered and disposed of.

"How is it possible that in 15 hours they burned so many boys, put them in a bag and threw them into the river?" she asked the AP news agency, external.

"This is impossible. As parents, we don't believe it's them."

The fragments of bone and tooth that were recovered from the site have been sent to Austria for DNA testing, but the attorney general has already said some are too badly damaged to ever be identified.

Meanwhile, in Iguala itself groups of desperate parents and local vigilantes are taking matters into their own hands.

I was in Iguala's main plaza last month as they gathered with shovels and pickup trucks to embark on another hot and harrowing operation into the thick vegetation around the town.

Acting on rumours and tip-offs from members of the local community, they search the hills and countryside, often entering dangerous drug cartel-controlled regions to dig for bodies.

"We've found 26 grave sites, which we have officially reported," said Cristofo Garcia, a member of the local self-defence force, which is helping the families in their search.

"We've found skeletal remains, bones, parts of human bodies which we've established don't pertain to the students. They're from older events, years ago."

Huge problem

It's a chilling thought. The mountains of Guerrero are seemingly dotted with mass graves.

Now though, with every day that passes, scores of families are breaking their silences over their disappeared children.

Demonstrators burn an effigy of the president during a protest in support of the 43 missing trainee teachers

If nothing else, Iguala has blown the lid off the huge problem of disappeared people in Mexico.

At least 26,000 people are unaccounted for over the past seven years. Such levels of disappearances are on a par with crimes committed during the South American military dictatorships of the 1970s.

Judging from the placards and chants on the streets - not just in Mexico City but across the country - it is the apparent involvement of the state in the young people's abductions, and possible murders, that has most angered ordinary Mexicans.

The federal government and President Pena Nieto have tried to place the blame firmly at a local level, characterising the issue as the result of weak municipal institutions that are too easily bribed and coerced by the drug cartels.

The president's response has been to propose the dissolution of all of the country's 1,800 municipal police forces.

They would be replaced with 32 state-level forces, which his office described as "trustworthy, professional and efficient".

But unpicking the tangled ties between local government and the drug cartels has been proposed before and no administration to date can point to any significant success in that endeavour.

Heroin trade

It is worth bearing in mind that the illegal drug trade in Mexico is worth anywhere between $30bn to $40bn a year to the cartels, generated by huge quantities of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and marihuana heading north to the United States.

Mexico is now the world's second biggest producer of heroin, and the mountains of Guerrero, where the disappearances took place, provide the ideal conditions for opium poppy production.

Protestors have mobilised across the country

With that kind of money and firepower at their disposal, the cartels have long been able to simply pay for political and institutional support or take it at gunpoint.

I am nearing the end of my posting in Mexico but an oft-repeated phrase on social media about Iguala - "#fueelestado" meaning "it was the state" - reminds me of a woman I met near the start of my time in the country.

We had travelled to the drug-war-ravaged state of Tamaulipas, where we interviewed then-presidential candidate, Enrique Pena Nieto, with days to go before the votes were cast.

Once he left, we travelled deeper into the state to meet a contact. After several furtive phone calls and changes of time and location, we eventually met "Susana" in a darkened hotel room.

For many years, she had been the girlfriend of a member of the feared Los Zetas cartel.

After showing us a series of gruesome videos of Zetas-led massacres, too violent to broadcast, I asked her just how close the relationship between the cartel and the security forces was in Tamaulipas.

"The relationship isn't just close", she explained - surprised that something so basic about the Mexican drug trade wasn't glaringly obvious.

"It's the very same people."

- Published27 November 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published7 November 2014

- Published29 October 2014