Acapulco struggles to shed violent image

- Published

Violence the Mexican city of Acapulco is taking a toll on the tourism industry, says the BBC's Katy Watson

It is early evening and a crowd has gathered on Acapulco's palm-lined beach road.

People are staring at an empty public bus, empty apart from a pair of legs sticking out near the rear stairwell.

This is Acapulco's latest crime scene. Less than an hour before we arrived, a man was shot dead as he was getting off the bus.

Police take notes and photographers take pictures.

Crime scene

It is the material that will fill the next day's crime pull-out in the local newspaper.

When I ask one of the bystanders whether this sort of thing is common, the man shakes his head and tells me that it is very rare.

I walk away and another man, Jesus Rodriguez, stops me.

"This happens a lot, it's a lie that he says that doesn't happen," he insists.

"It's really tough. Tourists aren't coming - and without tourism, there's no money in Acapulco. We all live on tourism in one way or another."

Dream location

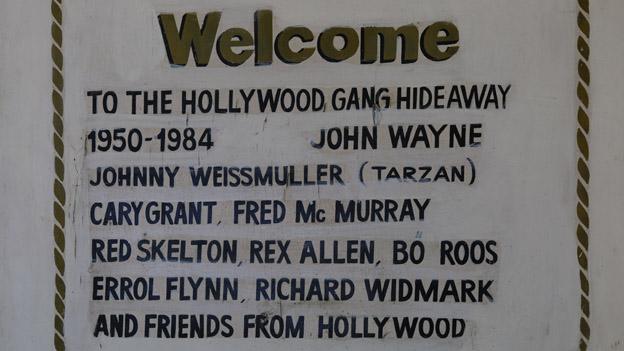

Acapulco was once a destination for Hollywood stars.

There are reminders of Acapulco's glamorous links with Hollywood all around

Elizabeth Taylor and John Wayne were just some of the names who came in its heyday, but drug-fuelled violence and street crime have given Acapulco more of a reputation for high homicide rates than for high-end glamour.

And when crime is not in the headlines, natural disasters are.

Acapulco was badly damaged by Hurricane Manuel in 2013 so the tourism industry has been hit hard in recent years.

The past few months have seen more problems.

Acapulco is in Guerrero state, the same as the town of Iguala, where 43 students went missing in September.

Violent protests in the months after their disappearance put tourists off.

The end of November is usually a weekend for Mexicans to celebrate the 1910 revolution and for hotels to celebrate because their rooms get booked up.

But last year was very hard. In the run-up to the weekend there were 14,000 hotel cancellations.

Around half of the rooms remained empty.

Police presence

Federal police have taken over security and policing from municipal forces in Acapulco.

The government sent federal forces to Acapulco in an effort to drive down crime

Officers patrol the beach road in pick-up trucks, wearing body armour and toting machine guns.

Even a minor traffic offence is met with armed policemen telling drivers they are stepping out of line.

But the federal police are not the only ones who have been sent to Acapulco.

More than 1,000 soldiers are protecting schools in neighbourhoods across the city.

Soldiers are now on watch at schools in the city

Their teachers went on strike late just before the Christmas holidays because of a spate of murders and kidnappings, some within schools.

Teachers only returned to the classrooms once they were guaranteed protection.

"The brutality of violence is getting worse and worse," says Walter Emanuel Anorve Rodriguez, who is part of CETEG teachers' union in Guerrero.

"As a sector, we are employed and we have the means to have a modest and stable quality of life - and so we've been targeted as a group that is able to pay a ransom."

'Speak well'

Down on the beach, people are trying to look on the bright side.

Acapulco's beaches have been more quiet than usual in recent months

Erick de Santiago runs a beach bar and is part of a group called Habla Bien de Aca, which translates as "Speak well of Acapulco".

Together with other local businessmen, he is trying to boost Acapulco's image and bring tourists back.

He says that with 80% of Guerrero's income coming from tourism, the federal government is not doing enough.

"It does damage us because people think twice about coming to Acapulco," he says about the violence, adding that security is not necessarily the most worrying issue.

"What's more important are the demonstrations, the blockades, people seizing control of pay booths on toll roads."

Impunity

While businesses worry about the impact of protests and violence, for the tourists that do venture to Acapulco, the golden sands of the Pacific beaches will likely guarantee a relaxing holiday.

"The violence is really directed at certain people here, whether it be people involved in drugs or other bad things," says Tina Phebus from Michigan who has been coming here for the past 27 years.

Crime scenes have become an all too common site in Acapulco

"I'm not involved in things like that so for me, I don't feel unsafe."

But the reality for many living in Acapulco's poorer neighbourhoods is that violent crime is not the only problem.

Jazmin (not her real name) says her daughter was murdered just over a year ago and despite the police knowing who her killers are, they remain free.

"My daughter was strangled with a steel cable, hands tied behind her back as if she was a criminal," says Jazmin.

"Justice hasn't been done. The government doesn't consider us, it doesn't want to believe there's a huge problem. We citizens have a right to security, to live safely here in Acapulco."

Brutal reality

We put Jazmin's situation to Acapulco's interim mayor, Luis Urunuela Fey.

In charge of the city until the mid-term elections in June, even he admits little can be achieved in that time.

Luis Urunuela Fey says corruption is everywhere

Acapulco's views and beaches are still for many

The armed bodyguards he travels with show the dangers people in power here feel, too.

"There are corrupt people everywhere," he says.

"It's not a justification nor an expectation that with some good people we can achieve things, but it is about knowing that we are all in the same boat. We can't have some people doing nothing and others leading the way, we all have to make an effort."

The federal police are making that effort, as are businesses here, too.

But the reality is brutal. The day after the man was shot on the bus, images of his bloodied body are splashed across the papers.

The page is shared with a man stoned to death naked and the murder of a taxi driver.

Tourists may be able to enjoy that dream holiday but the violence suffered by Acapulco residents is real.

- Published6 February 2015

- Published4 December 2014

- Published11 November 2014