How gang violence is spreading fear in El Salvador

- Published

All of the skeletons at San Salvador's Institute of Legal Medicine belong to victims of violence

Dr Oscar Quijano picks up a bone and excitedly explains how, just by looking at its texture, he knows how old the person was when they died.

Every day, he says, is a learning curve.

The forensic anthropology department of San Salvador's Institute of Legal Medicine feels like a history museum.

Laid out neatly on the tables are skeletons, each bone labelled and placed in position.

But these bones I am being shown do not tell me about El Salvador's history - they tell me more about what is happening right now.

Violent deaths

Some of these skeletons are no more than a year old.

Dr Quijano says the bones are either handed in after people stumble across them, or they are given to police by criminal gangs as part of a sort of plea bargain.

Each one of them belongs to someone who died in a violent manner.

One skull had to be carefully pieced together because the victim had her face smashed in.

Another skull has several bullet holes.

Many of the skulls bear bullet holes

Dr Quijano takes me to one table and picks up some vertebrae, pointing out that this victim was dismembered - most probably alive.

"Each different group or clique kills people in a different way," he tells me.

"Dismembering or strangling. Or a blow to the head. They all have their own execution style."

Crumbling truce

Dr Quijano says his team is struggling under all the work they are being given.

Many bodies are still awaiting identification in the morgue in San Salvador

In recent months, more and more bones have been brought to him to investigate.

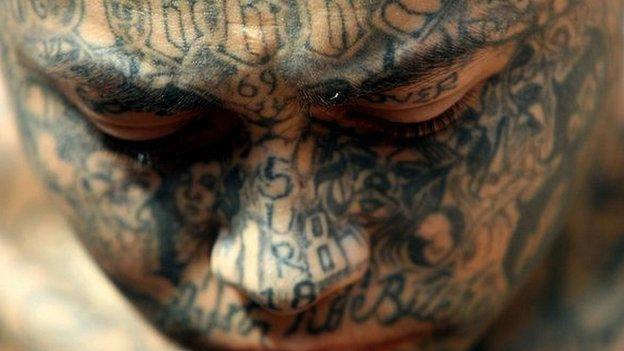

El Salvador is on track to become one of the most violent countries in the world, and much of that violence is down to the country's biggest gangs.

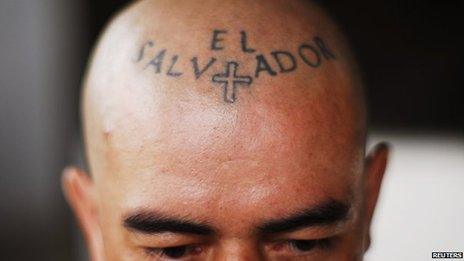

The Mara Salvatrucha and the 18th Street Gang both trace their origins to Los Angeles, where they were founded by Central American immigrants.

Gang graffiti shows who controls the neighbourhood

After many of their members were deported back to their home countries, they now control entire neighbourhoods in El Salvador.

In 2012, El Salvador's main gangs agreed a truce which initially reduced murder rates by 40%.

But the truce has all but crumbled and killings have now soared.

March was the deadliest month in a decade and there has been little let-up since.

'Hard life'

The family of Pedro Valladares Martinez knows this too well.

Pedro Valladares Martinez (in the picture) was killed while working as a bus driver

Last month, the father of five was at work as a bus driver when he was shot in the head.

Just a few days earlier, Mr Valladares had told his wife Margarita that his job was getting too dangerous.

He said he wanted to find something else.

"He came home at eight in the evening, he had dinner and watched a bit of sport on the TV," she tells me.

"When it finished, he called our five children over and said please behave, we live in such a violent place, even just looking at somebody you can get into trouble… you might not think it, but life is hard."

'No truce'

Critics say that the truce only served to expand the power of the gangs.

President Salvador Sanchez Ceren, who took office in June, has not recognised the truce and is opposed to negotiations with gang members as a way of tackling crime.

President Sanchez Ceren has ruled out negotiating with the gangs

But with homicide rates on the rise, many Salvadoreans fear the country may be facing another civil war.

They argue that gang warfare has replaced the guerrilla warfare and death squads which wracked the country from 1980 to 1992, when Marxist rebels of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) fought the government.

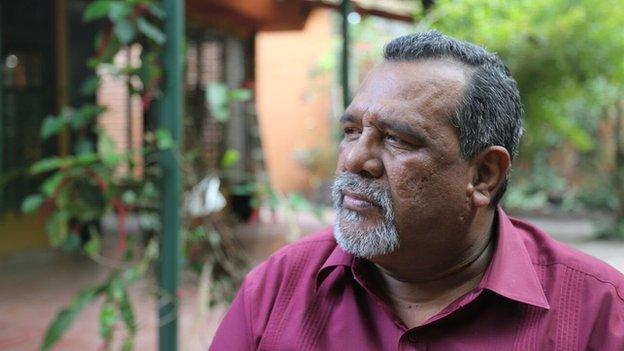

"Today, the problem El Salvador is facing is no longer an issue that's just between gangs," explains Raul Mijango, a former FMLN leader who helped broker the truce between the gangs three years ago.

Raul Mijango helped negotiate the truce between the gangs

"Now, what you have is a problem between gangs and the state."

With 70,000 active members and more than four times as many people in some way connected to or dependent on the gangs, this is not a problem the government can ignore, he argues.

"Around 11% of Salvadoreans are involved in the violence that this country faces, so you can't try and resolve a problem of this size just through clamping down on them."

Failed strategy

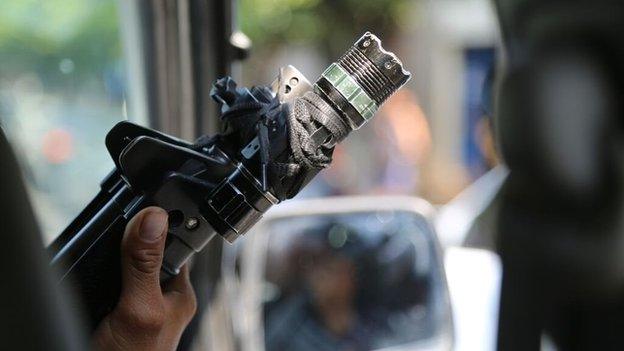

Police are increasingly becoming the target of attacks.

An anti-gang police force has been created, but murder rates have not gone down

A new anti-gang force has been created but so far it has not been able to reverse the upward trend of homicides.

So is a new truce the answer?

Deputy National Police Commissioner Howard Augusto Cotto says the iron-fist tactic has not worked in El Salvador, but negotiating with gangs is "a difficult subject".

"It's a strategy that cannot provide results," he argues.

Mr Cotto argues that negotiations with groups that have an ideology or a political vision have been successful.

Deputy Police Commissioner Howard Augusto Cotto thinks prevention would be best

"But here we're talking about a criminal activity," he says.

The police chief says there needs to be another solution, one that prevents crime in the first place.

But resources here are tight. And these gangs have just as much - if not more - firepower than the authorities they are fighting.

- Published30 August 2014

- Published25 March 2014

- Published20 December 2013