El Salvador: Digging to solve hundreds of gang murders

- Published

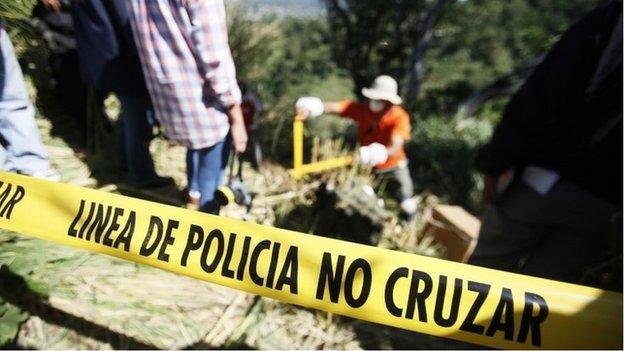

El Salvador is a nation riddled with gangs - and consequently has one of the highest murder rates in the world. Most crimes go unpunished, but one man spends his time in the mountains, digging up the forgotten victims.

It had taken a few furtive phone calls, but eventually Israel Ticas, known as The Engineer, agreed to meet me high up on a mountainside.

I had wanted to interview him and see the latest site he was working at, but his bosses weren't having that.

"I have been told off for talking to the media recently," he explained, his voice a hoarse whisper down the line.

"I can talk to you but solely in a personal capacity."

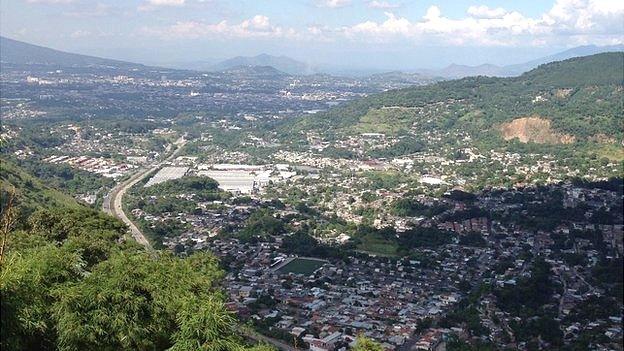

A couple of nights later, we drove up the snaking mountain roads to Juayua, a small town outside San Salvador.

Surrounded on both sides by rich jungle, the altitude makes it the perfect environment for coffee plantations. And the perfect environment for hiding dead bodies.

Although he doesn't like the title, Israel Ticas is El Salvador's only forensic archaeologist.

A short, wiry guy with a dark, lined face, the result no doubt of so many hours working outside, he is shivering in the bitterly cold mountain air. We retire to a nearby restaurant to get warm.

Still wearing his hard hat, the dig he has come from was no hunt for Mayan pottery or dinosaur bones. It was a mass grave.

In El Salvador, Ticas is also known as The Engineer, a reference to the fact he initially studied computer engineering before turning his mind to solving murders.

"Forensic archaeology was unknown here in El Salvador," he tells me, his hands cupped around a mug of hot chocolate.

He learnt his skills as a criminal investigator abroad, particularly on visits to Africa where he worked on sites of mass killings and genocide.

Then he brought the DNA and victim identification techniques he had seen back to his native El Salvador - until recently the country with the highest murder rate in the world.

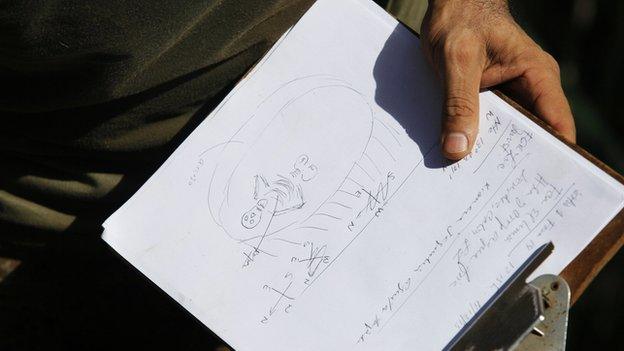

"What I did was fuse those methods," he says, "adapt and apply them to the criminal gangs and their modus operandi here."

Certainly El Salvador's drug war has kept him in work.

"I've identified 25 different methodologies of murder," he explains with the matter-of-factness of a scientist.

"Every criminal mind is different. But each of them innovates too.

"For example, when dismembering a body, if one person disposes of it in seven parts, someone else says 'I'm going to turn it into 20'," he says.

It is a sobering thought, and over the course of our conversation, he reveals many more grisly details, most of which are far too gruesome to repeat.

I want to know how such daily exposure to the country's extreme violence makes him feel - as a citizen rather than as a scientist.

"It makes me sad," he says, his first reference to emotion.

"I don't agree with anyone's right to take away the life of someone else - especially when it's a Salvadoran taking the life of another Salvadoran," he adds.

But then, it's quickly back to the relative safety of empirical science.

"I've worked on more than 2,000 crime scenes. Thanks to God for giving me this little bit of intelligence, I've been able to recover bodies from places no-one could have recovered them from.

"I've recovered people who were buried 60 metres deep, got all 206 bones of the body back, all that evidence. That is what gives me professional satisfaction."

Ticas was the subject of a recent documentary in which the filmmakers followed him as he exhumed remains from quarries and mines, shallow graves and deep pits across the country.

Often, the grieving mothers of the victims come to urge him personally to find their missing loved ones, heaping further pressure on a man already under considerable strain.

At times that strain begins to show.

More than once he mentions the difficulty of working on the bodies of dead children, of holding a six-year-old's skull in his hands and having to think of it as just evidence, as "material".

"I give conferences in university psychology departments and I tell them 'you should study me. What's wrong with me?'

'How can I work cleaning the face of a dead baby with a brush for two days and not feel anything?'"

His rhetorical questions hang in the mountain air.

"But then sometimes I might suddenly drop the brush, look to the heavens and ask God 'how can you allow this to happen?'"

His morbid fascination could just be the natural by-product of work which has undoubtedly brought some closure to hundreds of families in El Salvador.

An inherently private man, Ticas insists he is unaffected by post-traumatic stress.

Yet something he said revealed a little of what it must be like to be The Engineer of El Salvador: "Sometimes I feel like I'm living in a film. But then, when I open my eyes, it's reality."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published9 July 2024

- Published21 November 2012

- Published20 November 2012

- Published22 January 2014

- Published22 January 2014