Should drug lord Guzman have been extradited to the US?

- Published

After his arrest in 2014, the Mexican authorities said they wanted to put him on trial in Mexico

The escape on Saturday of Joaquin Guzman, one of the world's most wanted drug lords, from a maximum-security jail in Mexico, has reignited the discussion about whether he should have been extradited to the United States.

US prosecutors had been expressing their wish to put him on trial in a US court since his arrest in February 2014.

Guzman, who was named Public Enemy Number One by the Chicago Crime Commission in 2013, has been indicted by at least seven federal district courts.

As the head of the Sinaloa cartel, he is accused of overseeing the smuggling of huge amounts of drugs from South and Central America to the United States.

He is also facing charges of money laundering, racketeering and arms trafficking in courts as far apart as Arizona and Texas.

'No intention'

But since his 2014 arrest in his home state of Sinaloa, Mexico, there has been little movement on the extradition front.

While US courts were arguing about who had the best case against Guzman and should therefore get priority putting him on trial, Mexican officials were making it clear they were in no rush to send him across the border.

Mexico's attorney general at the time, Jesus Murillo Karam, said as early as April last year that he had "no intention" of handing Guzman over to the US authorities.

Jesus Murillo Karam was attorney general at the time of Guzman's arrest

In an interview with Mexican daily El Universal, Mr Murillo Karam said he was annoyed at a plea bargain an extradited Mexican drug dealer had struck with the US authorities.

Jesus Vicente Zambada Niebla, also known as Vicentillo, pleaded guilty in a court in Chicago to smuggling tonnes of cocaine and heroin to the United States.

In exchange for promising the US authorities "full and truthful co-operation", his sentence was reduced from a potential life sentence to 10 years.

Valuable asset

The US authorities believed Vicentillo could prove a key witness if Joaquin Guzman was ever extradited to the United States.

The son of Guzman's number two, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, and a key player in the drugs trade himself, Vicentillo was seen as a valuable asset.

But Mr Murillo Karam said he felt "uncomfortable" with the deals the US reached with "criminals" such as Vicentillo.

The then-attorney general pointed out that there were plenty of charges Guzman faced in Mexico as well as in the US and that he wanted to see him tried in his homeland.

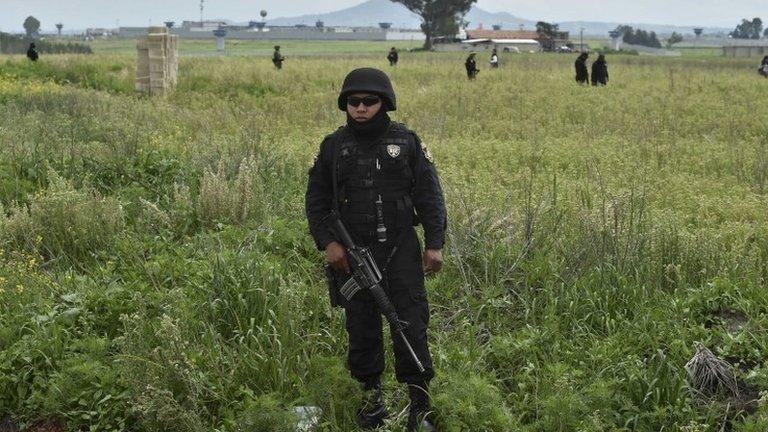

Guzman's associates managed to build an elaborate tunnel, raising suspicions the guards may have been involved in his escape

He reiterated his position in January of this year, when he again stated that he wanted to see Guzman serve his sentence in Mexico first.

'El Chapo [Guzman] has to stay here to serve his sentence and then I'll extradite him. That could be in about 300 to 400 years, there's still a long time to go."

At the time, he said that he thought a formal extradition request by the US was imminent, but it seems that following Mr Murillo Karam's strong words, the request was not filed.

He argued that keeping Guzman in Mexico was also a question of sovereignty.

But Mr Murillo Karam is more likely to regret another statement he made back in January.

He said that extradition should be considered in instances where there was a flight risk, something he said did "not exist" in the case of Guzman.

Given the fact the Guzman had escaped from another top security jail in 2001 and was on the run for the next 13 years, this was a surprising assurance.

Colombian experience

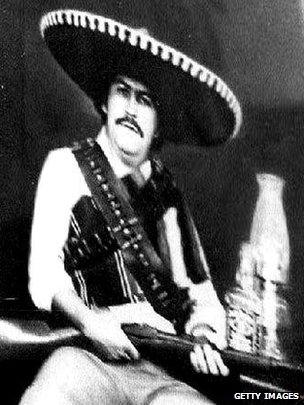

Escobar liked to style himself as a rebel

Comparisons have been drawn between Joaquin Guzman and the late infamous Colombian drug lord, Pablo Escobar.

Both made immense fortunes in the illicit drug trafficking trade, and through bribery and intimidation managed to sway huge power and infiltrate parts of the security forces.

Both have also mounted successful and spectacular escapes from jail.

It was Pablo Escobar's jail break that played a major part in changing the Colombian approach to extradition.

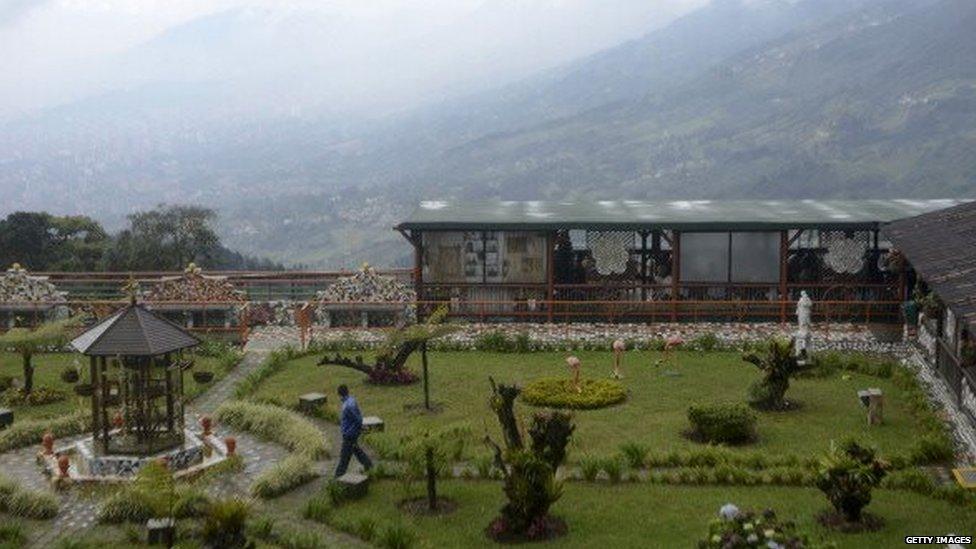

In a 1991 deal with the Colombian authorities, Escobar agreed to hand himself in to the Colombian police and to serve five years in a jail built to his own specifications in his hometown of Medellin.

La Catedral (the cathedral), as the luxury jail was known, boasted a football pitch, a jacuzzi and a bar among its many amenities.

Escobar's prison overlooked his hometown of Medellin

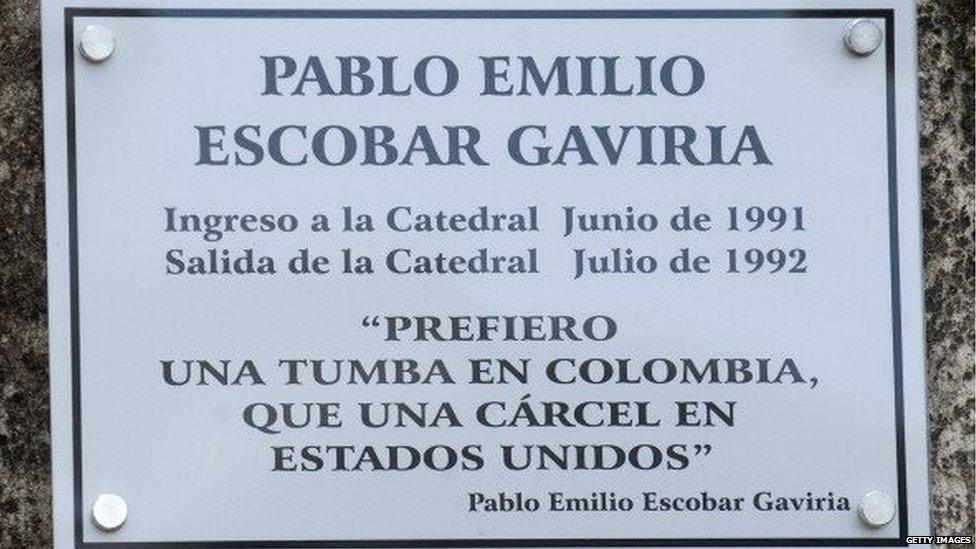

A plaque at the site of the Catedral prison recalls Escobar's words that he preferred "a grave in Colombia to a prison in the US"

After little more than a year, Escobar escaped from the jail and went on the run, much like Guzman did on Saturday.

He was eventually killed a year later while still on the run.

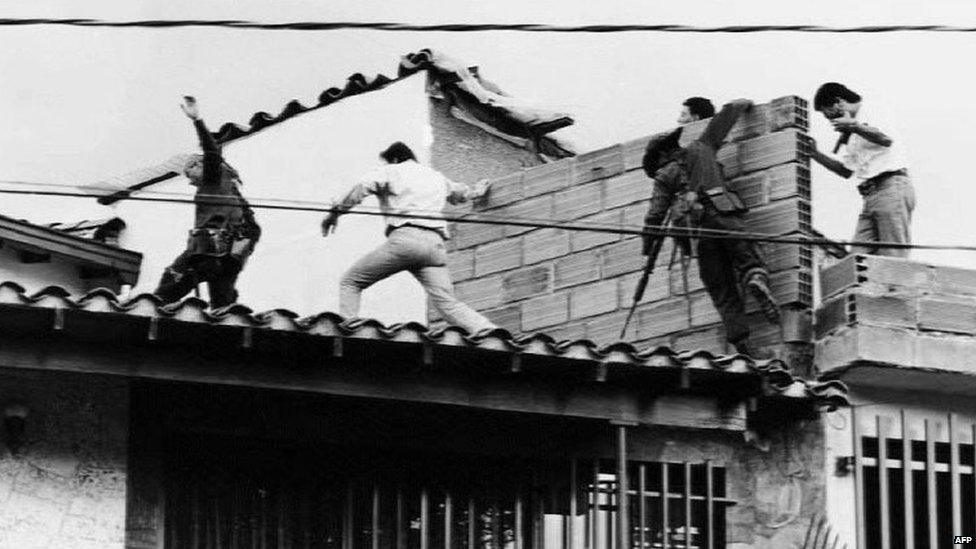

Pablo Escobar was shot dead on a rooftop in Medellin, pursued by Colombian security forces

But before he was jailed, Escobar had threatened and cajoled members of a constitutional assembly to enshrine a ban on extraditions in the Colombian constitution.

It remained in force until December 1997, when a constitutional amendment reversed the ban.

Since then, Colombia has extradited many drug dealers to the United States saying that it is both a cheaper and safer option for the Colombian justice system.

Colombian officials argue that in the US, Colombian drug dealers will find it harder to intimidate guards and their families or to access their riches to bribe prison staff.

With 30 prison staff and the warden under questioning over the escape of Chapo Guzman at Mexico's Altiplano jail, this argument may well be met with more open ears in Mexico, too, now.

- Published13 July 2015

- Published1 March 2014

- Published22 February 2014