Montserrat: Living with a volcano

- Published

Soufriere Hills erupted 75 times in a single month in 1997 and is still one of the most active volcanoes in the world

There is little danger of being late for lunch in Montserrat.

At 12:00 sharp every day, the mournful wail of the tiny island's volcano sirens cut through the air like a knife.

The ominous soundtrack to life in this British overseas territory can be heard across inhabited parts of its 100 sq km (39 sq miles).

Residents know if the sirens blare at any moment but noon, it's time to run - fast.

Volcano sirens such as this one are tested daily at noon

Taunting in its perpetuity is the steam and bluish haze of sulphur dioxide emitted from the slumbering monster in the south, whose constant threat pervades the atmosphere like a viscous liquid.

Incessant activity

This is the reality for those living in the shadow of Soufriere Hills.

Last month, Montserratians marked 20 years since the start of the volcanic crisis which has rendered two-thirds of the island an exclusion zone, turned the capital city into an apocalyptic movie scene deep in ash and changed life here forever.

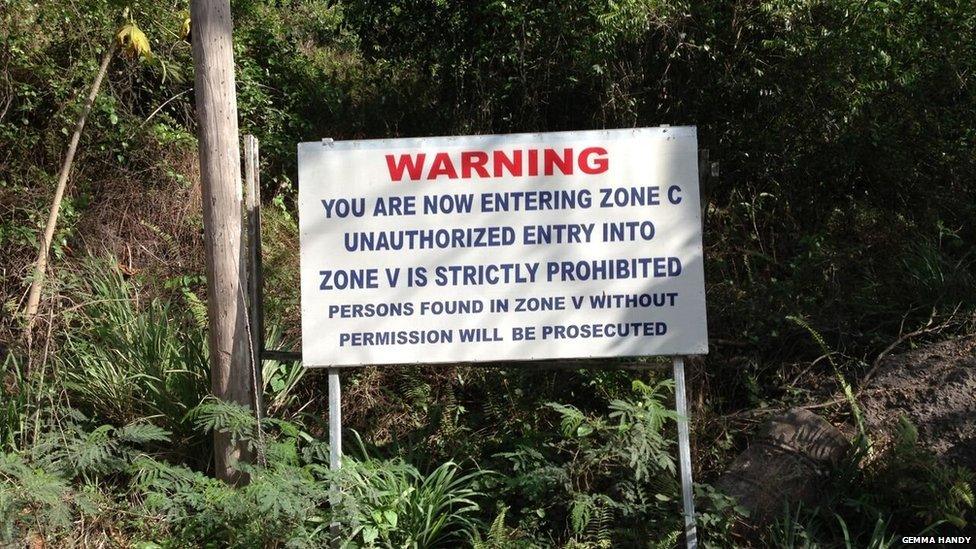

Two-thirds of the island remains within an exclusion zone

Few imagined when a vent in the volcano - dormant for several hundred years - began smoking on 18 July 1995 that it would awaken with such a vengeance.

Or that its incessant activity, rather than the sudden brief explosions favoured by Hollywood, would continue to this day.

Back in the early 90s, Montserrat's future looked bright.

A mammoth cleanup after devastating Hurricane Hugo in 1989 had seen the construction of much modern infrastructure and the territory was experiencing unprecedented prosperity.

There was even talk of independence from Britain.

Fiery spectacle

When the hills first started to emit their brilliant white steam, islanders say it was mesmerising and exciting. People would gather in the evenings to watch the fiery incandescence in awe.

It was 14 months before the first eruption took place in September 1996, sweeping away the villages of St Patrick's and Morris in less than 20 minutes.

Whole villages were buried under ash or destroyed by lava flows

A photo from 20 August 1997 shows how lava flows from the volcano covered large areas

That year, the capital Plymouth was evacuated for the final time - abandoned to become slowly buried under repeated mudflows - and a state of emergency declared.

Today, Soufriere remains one of the most active volcanoes in the world.

The population has plummeted from 11,500 to 5,000 with the south of the island divided into five zones.

Permission to access them is dependent on the current hazard level.

Strong bonds

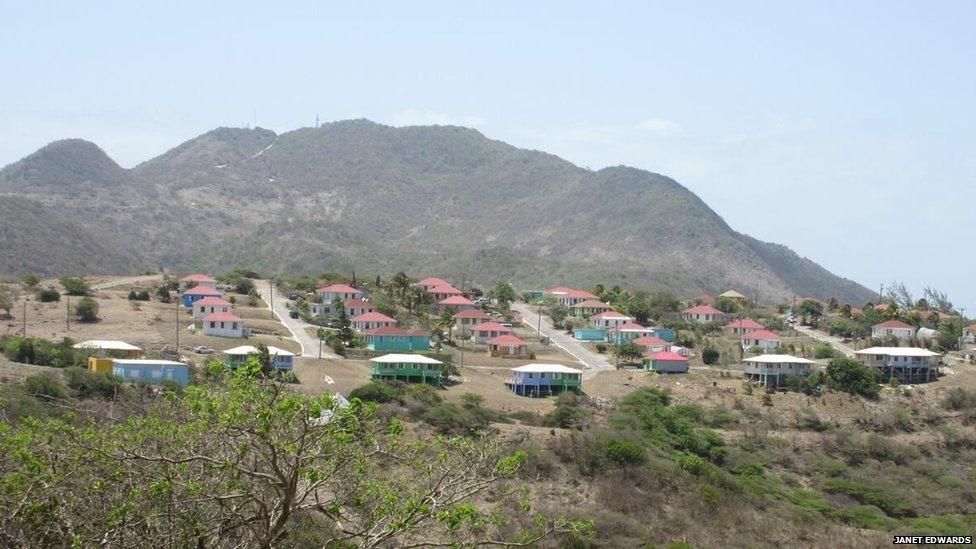

Over the years, businesses have rebuilt in the north, municipal offices have relocated to Brades and the government has created new housing at Lookout, Davy Hill, Shinlands, Drummonds and Sweeneys.

The government has built new housing in Lookout in the north-east of the island

Despite the gases and ash falls - which occasionally reach as far as Antigua - Montserrat's stoic inhabitants largely go about their business unperturbed, refusing to be defined as living on the precipice of peril.

Tourists are politely told that "Montserrat is not a volcano; it has a volcano" and assured that the north remains entirely safe, with Soufriere under round-the-clock monitoring by a purpose-built observatory.

As is often the way in the aftermath of disaster, the close-knit community has forged stronger bonds than ever.

Crime is a rarity, front doors are unlocked, songs of hope and healing, solidarity and unity, are ubiquitous.

The island's distinctive "black sand" beaches get their colour from minuscule pieces of lava

These days, the "emerald isle" is carving a niche for itself in adventure tourism with holidaymakers attracted to its "black sand" beaches and the allure of experiencing a modern-day Pompeii.

Future plans

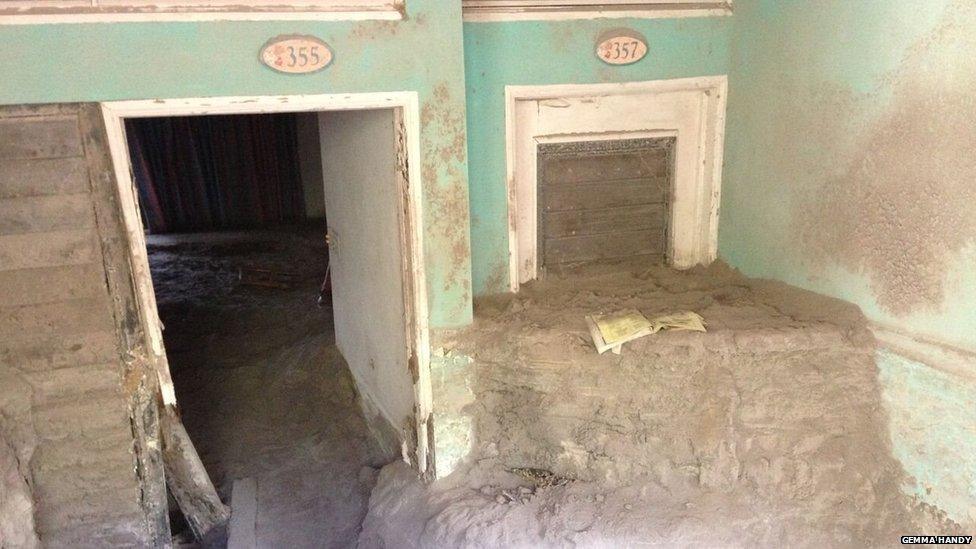

In the ruined Montserrat Springs hotel - once one of the island's finest - visitors can scrabble through the ash into the reception where paperwork still sits on the desk and into bedrooms where curtains hang against wrecked walls.

Montserrat Springs hotel was once the jewel in the island's tourism crown

Ash still covers the inside of the rooms

Vegetation has taken hold in some of the formerly elegant rooms

From the side of the ravaged swimming pool, Plymouth is visible just east of a huge fissure which appears in the desolate landscape like a jaw wide open in astonishment.

Veronica Hickson's house is one of the few in Plymouth that's not completely buried.

She recalls the evacuation order that came on 3 April 1996. "I've been back since to see my house," she says. "It's sad but we have to continue our lives."

The ravaged former capital of Plymouth is visible on the horizon

In addition to tourism, hope for the future lies in geothermal energy exploration and the exportation of volcanic sand for construction.

Islanders are keen to reduce reliance on Britain for financial help - £420m ($655m) since 1995.

Former Governor Frank Savage, who presided over affairs from 1993 to 1997, recently paid tribute to the "stoicism" of Montserratians and their "indomitable spirit" which he said would lead to ever greater recovery.

New Governor Elizabeth Carriere, who takes up position this month, agrees. "Montserrat's future lies in the hands of its most valuable resource: its people," she said.

"I will work with the island's government to realise a safe, sustainable and prosperous Montserrat."

Ms Carriere added: "Better sea links, tapping opportunity for geothermal energy and improving technological links to the wider world all have a part to play."

- Published3 April 2014