Dying off: Antigua's struggle to save the coconut palm

- Published

The image of healthy palms on Antigua is one that is increasingly less common

White sand beaches fringed by lofty palm trees - it is the image of a tropical paradise that has lured holidaymakers to the Caribbean for decades.

But in tourism-dependent Antigua, a deadly disease has wiped out almost half of the island's majestic coconut palms - leaving unsightly headless trunks littering the landscape.

Lethal yellowing, the same condition that devastated the iconic trees in Florida and Jamaica, also strikes at the heart of this 280sq km (108sq mile) island's culture and economy.

Here, coconut products are used in everything from food and drink to beauty treatments and traditional medicine.

Around 45% of Antigua's thousands of coconut palms have been lost to date, estimates Barbara Japal, president of the island's Horticultural Society.

'Palm is the charm'

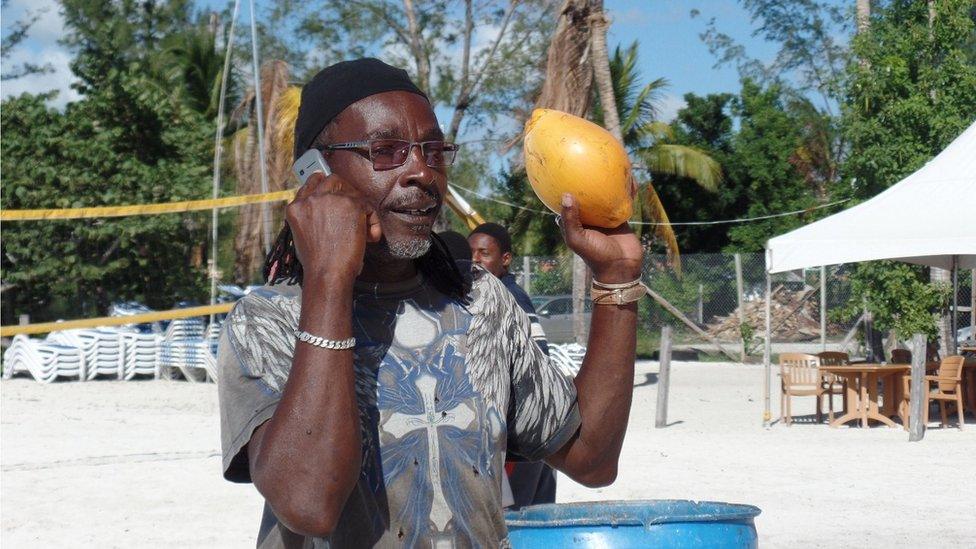

Street vendor Julian Rose is one of those affected.

He has been selling coconut water for $3.70 (£2.40) a bottle for four years, but says the last 12 months have seen supplies nosedive by half - as has his income.

"I've kept my prices the same - people won't pay more," he says.

The official advice states that palms showing signs of the contagious disease, characterised by premature shedding of fruit and yellowing fronds that eventually drop off, should immediately be cut down and burned to prevent the disease spreading.

But the cash-strapped government's lack of resources has enabled it to run rampant, with the trees dying in droves since lethal yellowing was first identified in 2012.

In some parts of Antigua, efforts are made to protect palms - other parts are not so lucky

"It affects tourism because, as we say, the 'palm is the charm' and it really diminishes what the seascape looks like," Mrs Japal tells the BBC.

"It's devastating to see them standing there looking like beheaded soldiers. It's shocking, it feels irreverent.

"Coconuts are used in so many aspects of daily life here too; people cook with them, put the oil on their skin and hair. And while it may not be part of conventional medicine, it's part of our tradition to use the oil to heal the skin and cleanse the body."

Imported threat

Lethal yellowing is spread by a plant-hopping insect that Mrs Japal believes was probably brought into the country with imported trees. A ban on importing palms has been in place since 2012.

"We had so many plants brought in some years ago," Mrs Japal continues.

"We have a plant protection unit but when you have a container with 3,000 trees, who's going to inspect every one?"

She says underfunding had left staff's hands tied. "There's no proper disposal or systematic removal of affected palms unless private individuals take action."

There is currently no cure for lethal yellowing, although trees can be treated with quarterly injections of the antibiotic oxytetracycline (OTC).

"Local people are not using OTC; it's just too expensive," Mrs Japal adds. "The resorts are the only ones that can afford it."

Coconut vendors, seen here working in the shadow of dying palms, are feeling the pinch

John Murphy, maintenance manager at the Carlisle Bay luxury resort, says bosses had decided to "be proactive rather than reactive" to protect the venue's hundred palms.

The cost of treating each one with OTC every three to four months is around $450, he says.

"It's not cheap and a side effect is that it's not recommended to consume the coconut milk or jelly for a year after a tree's been treated," Mr Murphy says.

"Personally I don't believe the antibiotic is 100% successful unless it's administered every few months for the life of the tree - and they live to be 60 or 70 years old."

He says bureaucracy has slowed the process of curbing the disease. The antibiotic must be imported with a special licence - but this is issued only after the presence of lethal yellowing has been officially confirmed.

The $150 cost of the test is also prohibitive for many people in a country where the minimum wage is just $3 an hour.

"It took almost a month to get the licence when we were promised we'd get it within a week," Mr Murphy says.

'Not much more we can do'

Such is the disease's ferocity, an untreated palm usually dies within three to six months.

The affected palms turn yellow

Martin Dudley, an ecological activist, says farmers and nurseries should be encouraged to grow replacement palms to supply hotels and holiday villas.

"The trees still standing where others have died, that show greater genetic strength, should be allowed to come to term - rather than harvesting the nuts for jelly - to provide seeds for new trees," he says.

Kishma Primus-Ormond, a government plant protection officer, says authorities are inspecting as many suspected cases as they can while cutting down affected palms to halt the spread and clean up the island.

"We don't have any funds," she adds. "There's not much more we can do."

As Antigua's new tourist season swings into gear, many are hoping that this will be enough.

- Published4 August 2015

- Published20 May 2014