Pope and Russian patriarch edge towards warmer relations

- Published

Both Church leaders have found they have issues of mutual concern

Pope Francis' meeting with Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia will be the first between a leader of the Roman Catholic Church and a spiritual head of Russian Orthodoxy since their Churches split in the 11th Century, mainly over the issue of papal authority.

Its significance for both Churches is immense. Whatever the joint declaration they sign when they meet in Cuba on Friday, the simple fact of their meeting is a clear signal the hostility and chill of the past thousand years or so since the Great Schism, external may finally be edging towards a warmer phase in relations.

That relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church matters because about two-thirds of the world's more than 200 million Orthodox Christians are Russian.

Earlier popes tried to pave the way for such a thaw with Moscow, most notably Pope Saint John Paul II, who tried to reach out to the Russian Orthodox Church.

However, those efforts were hindered by post-Cold War suspicion - above all in Moscow - which was only added to by the Pope's own Slavic roots.

This "personal conversation" between the two leaders at Jose Marti International Airport in Havana has been made possible by many relatively recent geopolitical shifts.

'Ecumenism of blood'

One of the main drivers of this meeting was the realisation over the past few years that when Christians are persecuted or driven out of their homes in the Middle East and Africa, their killers are not interested in which Christian denomination they come from.

It is what Pope Francis has termed the "ecumenism of blood", and the Pope, the Russian president and the Russian patriarch regard what is happening to Christians in Syria and Iraq as genocide.

The Pope's own heritage as the world's first Latin American pope, allied to his recent diplomatic efforts in Cuba, Moscow and elsewhere, may also have been one of the factors helping to nudge the Orthodox Church towards agreeing to the meeting.

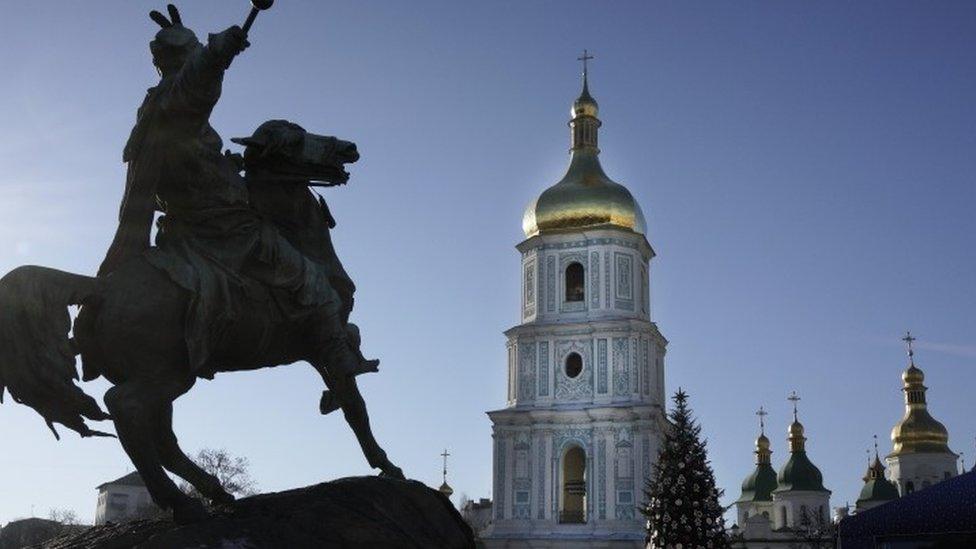

Many Russians view the Western Church's influence in Ukraine with suspicion

Pope Francis is seen in Moscow as a leader who does not necessarily instinctively agree with the US, despite his warm reception there last year, and whose instincts incline towards dialogue rather than confrontation.

Some in Russia still worry about the Western Church's influence in Ukraine in particular, where the Greek Catholic Church is viewed with hostility by many Russian Orthodox. They see it as encroaching on Moscow's canonical turf, and taking a mostly anti-Russian political stance.

Under the leadership of Josef Stalin, the Soviet Union handed over Eastern Catholic churches to the Orthodox Church.

But following the collapse of Communism, the Catholics took back some 500 churches, mainly in Western Ukraine in the 1980s and 1990s, to the bitter dismay of the Orthodox.

Likewise, post-Soviet Russia worried about Catholics trying to win over the Orthodox faithful in its sphere of influence after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a period when missionaries from many denominations headed east to win converts - although very few Orthodox actually converted to Catholicism.

Patriarch Kirill has warmer relations with the Kremlin than some of his predecessors

However, Russia's Orthodox Patriarch Kirill has also made warmer overtures over the past few years than his predecessors.

He is much closer to the Kremlin than previous patriarchs. It's thought that he would have been unlikely to have agreed to the meeting with Pope Francis without some kind of tacit acceptance of the move from President Vladimir Putin, who has visited the Vatican and met several popes during his years in power.

Moscow may also be keen to reassert its relevance on the global religious stage, as well as in secular foreign affairs, after its decades of official Soviet atheism.

Now that the Vatican is again proving itself a diplomatic force to be reckoned with, Russia is perhaps keen to keep the Vatican onside.

It is proving a useful interlocutor between East and West on issues ranging from the war in Syria to the protection of Christians across the Middle East, while the Vatican is also a potential theological ally in the question of how to deal with the global threat from radical Islamism.

All this does not mean that the Great Schism or East-West Schism of 1054 is yet at an end, nor that Christian unity is nigh, but respectful dialogue is likely to be the order of the day in Cuba.

No Pope has ever visited Russia. So perhaps this meeting in Cuba might just pave the way for yet another first for a papacy that continues to be full of surprises.

Who are the Orthodox?

The Orthodox Church is one of the three main Christian groupings, alongside Roman Catholics and Protestants.

It is made up of Churches that are either autocephalous (meaning having their own head) or autonomous (meaning self-governing).

The word "Orthodox" comes from the Greek words "orthos" (correct) and "doxa" (belief).

The Orthodox Churches are united in faith and by a common approach to theology, tradition, and worship.

They draw on elements of Greek, Middle-Eastern, Russian and Slavic culture.

The Orthodox tradition developed from the Christianity of the Eastern Roman Empire and was shaped by the pressures, politics and peoples of that geographical area.

Since the Eastern capital of the Roman Empire was Byzantium, this style of Christianity is sometimes called Byzantine Christianity.

The Orthodox Churches share with the other Christian Churches the belief that God revealed himself in Jesus Christ, and a belief in the incarnation of Christ, his crucifixion and resurrection.

But they differ substantially from the other Churches in the way of life and worship, and in certain aspects of theology.

- Published5 February 2016

- Published28 October 2022

- Published14 March 2013

- Published16 August 2012

- Published5 April 2012