Pope Francis makes symbolic trip to troubled Mexico

- Published

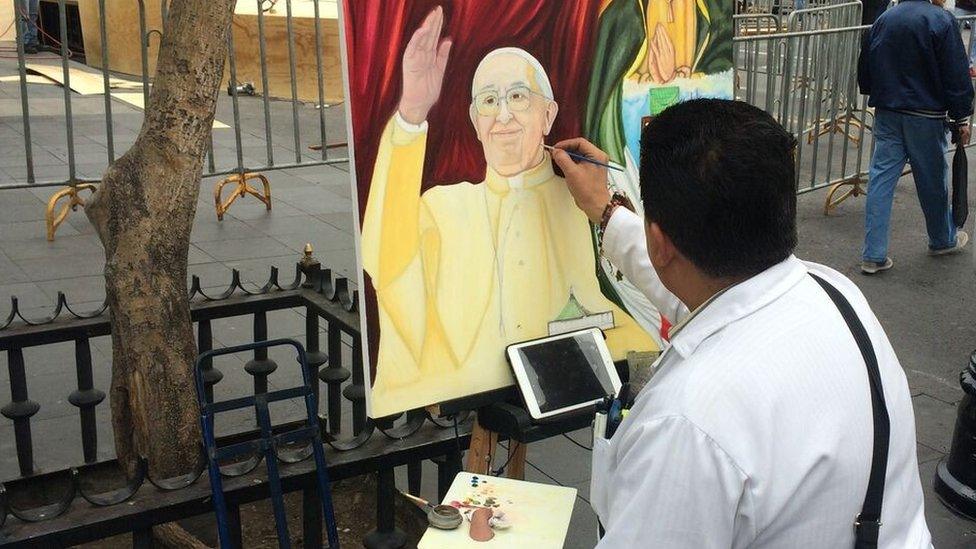

Jorge Santamaria sits at his easel outside Mexico City's cathedral, palette in hand.

He is putting the finishing touches to a portrait of Pope Francis.

"This is a homage to him," he says. "Coming to Mexico, meeting us and praying for our virgin is very important - that's why I'm painting this."

There is a great deal of affection towards the Argentine Pope here and a lot of excitement ahead of the pontiff's first visit to Mexico, which has the second biggest Catholic population in the world

The Pew Research Centre estimates 81% of Mexicans identify as Catholic, and Mexicans feel that as a fellow Latin American, Pope Francis understands the Mexican people.

Source of pride

One of the highlights of his trip will be the Pope's visit to the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico City.

Millions of pilgrims visit the site in honour of Mexico's patron saint every year, and they see it as a source of pride that Pope Francis will do so too.

"The impact will be huge, it's great for people because of all the violence here - we have faith that this could change things," said Fernando Medina, who was visiting the Virgin with his daughter Sofia.

The Pope will also meet President Enrique Pena Nieto in what will be a highly symbolic encounter.

In 1917, the Mexican constitution limited the role of the Catholic Church in public life, and Pope Francis is the first pontiff to be invited to the National Palace.

"The state is very conscious of Francis' popularity and his huge standing particularly in Latin America," says Austen Ivereigh, author of a biography of Pope Francis.

"I think they want to be identified with it - they want a bit of the stardust that attaches to Francis."

The Archbishop of Acapulco, the Most Reverend Carlos Garfias Merlos, says his congregation live in uncertainty and fear of getting caught up in violent situations

President Pena Nieto's approval rating has been hit by the country's continuing struggles with drug violence, human rights abuses and corruption scandals.

Pope Francis condemned the situation ahead of his visit, saying Mexico was living its "little piece of war".

"The Mexico of violence, the Mexico of corruption, the Mexico of drug trafficking, the Mexico of cartels, is not the Mexico our mother wants," he said.

Priests killed

And it is a war the Catholic Church in Mexico itself is not immune to.

Since Mr Pena Nieto became president four years ago, 12 priests have been killed and two are missing.

These figures suggest Mexico is now one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a priest.

"A priest by his very nature is a preacher who leads, who helps form opinion in his communities," says Father Omar Sotelo, the director of the Catholic Multimedia Centre.

"But this has made things difficult, it's inconvenienced organised crime.

"Organised crime is trying to put fear into people, to corrupt organisations, and obviously killing priests is destabilising the social fabric."

And, says Father Sotelo, "things aren't getting better".

Living in fear

The seaside resort of Acapulco used to be the holiday destination of choice of Hollywood stars, but now it is more famous for being one of the most violent cities in the world.

The Archbishop of Acapulco, the Most Reverend Carlos Garfias Merlos, says residents live in fear.

"They live with uncertainty and the risk that at any moment they could get caught up in a stand-off, they could be attacked even if they have nothing to do with the problem," he says.

Father Jesus Mendoza hopes the Pope will discuss corruption and links between politicians and organised crime

From the surrounding hills, there is an incredible view of the bay and the beach.

But the hillside community of La Laja, with its half-built houses, winding roads and sewage problems, is also one of the poorest and most dangerous neighbourhoods of Acapulco.

Father Jesus Mendoza has been the priest there for more than 20 years.

He knows who the criminals are and says they constantly watch him, meaning he has to be careful with his sermons.

"If I say something careless, that could put me in danger and I would have to leave, and I don't want to leave," he says.

"I want to be here because I know that people need me, so I have to put limits on what I say and the words I choose."

'Sore subjects'

Father Mendoza is hopeful the Pope's visit to Mexico, during which he will take in the violence-ridden border town of Ciudad Juarez and the poor southern state of Chiapas, will have an impact.

"We hope he'll touch on sore subjects," he says.

"High levels of corruption and the links between politicians and criminals - that is where this country gets stuck."

Pope Saint John Paul II attended a rodeo in Mexico City in 1979 but was not invited to the National Palace

The problem in Mexico is that many see bringing an end to violence and corruption as impossible tasks.

"Mexico's deep, deep problem is despair," says Mr Ivereigh.

"I think Pope Francis comes with the message to say it is possible to work through all of these things.

"But to do that you have to reconnect with the people and their suffering and their realities.

"You can increase the security as much as you like, [but] Mexico can only change when hearts and minds are converted.

"That's really what he's come to do."

The Roman Catholic Church in Mexico

Spanish adventurers accompanied by Roman Catholic priests reached Mexico in the early 16th Century, leading to conquest and rule by the Spanish of what they called New Spain.

After Mexico's independence in 1821, Catholicism remained the dominant religion, with the Church retaining a privileged status.

From the mid-19th Century, the state began to curtail the Church's role in education and restrict its power.

Anticlerical measures were strengthened in the 1917 constitution, leading to a rebellion in central and western states in the 1920s.

A new constitutional framework in 1992 removed many of the restrictions, granting legal status to religious institutions, limited property rights and voting rights to priests.

Today, Mexico has the second highest Roman Catholic population of any country (after Brazil); the 2010 census put the number, external of Mexican Catholics at 93 million.

However, evangelical Protestant churches have been reporting steady and significant growth for more than three decades.

- Published11 February 2016

- Published10 February 2016

- Published28 October 2022

- Published14 March 2013