Venezuelan social housing: Division over right to buy

- Published

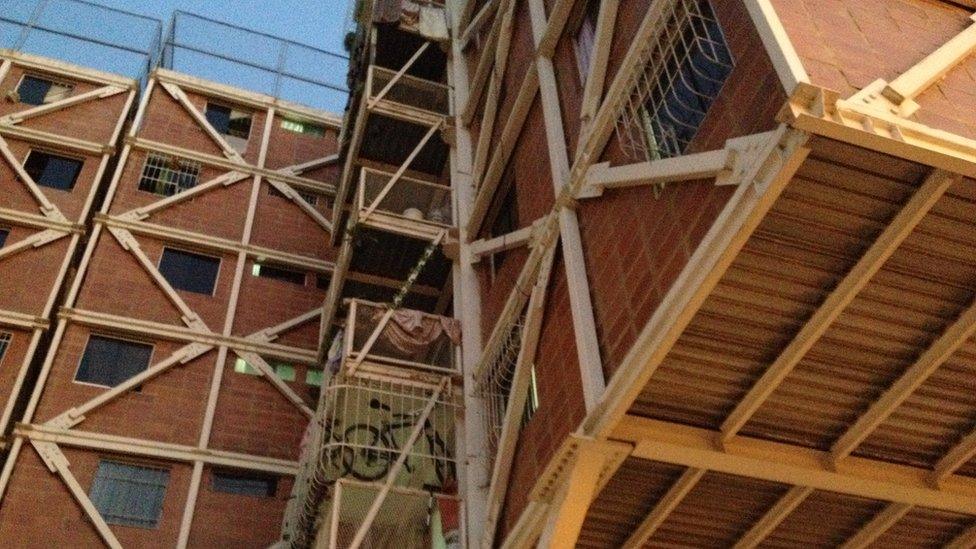

Marta Mendivil lives in Santa Rosa, a government-built housing estate in Caracas

Marta Mendivil and her family used to live in a single room in a shanty town in Caracas.

When it rained she had to bale out the water that poured through the roof.

Now Mrs Mendivil, her husband and their two children live in a three-bedroom apartment in the Santa Rosa estate, a government-built housing complex just next to the shanty town she once inhabited.

"Thanks to the revolution, I now have a decent house in which to raise my children," she says, referring to one of the key policies of Venezuela's socialist government.

Marta Mendivil and her family are happy to have a roof over their heads that does not leak

According to government figures, a million Venezuelans have been rehoused as part of Mision Vivienda (Mission Housing).

Many of the 420 families living on the Santa Rosa housing estate originally lived in the same shanty town as Mrs Mendivil.

The government says it intends to continue building apartments to make sure those remaining in the shanty town will be rehoused too.

Home of their own?

The new apartment buildings are made of red breeze blocks with aluminium roofs. The residents plaster and decorate their flats when they move in.

Residents of Santa Rosa are proud of their new homes

None of the residents of the Santa Rosa estate have started paying for their homes since moving in three years ago.

The government says that once it has assessed their means, residents will be given a long-term payment plan.

The payments will be calculated on what it cost to build the houses, not on the market value of the property.

Residents can occupy them for life and pass them on to their children.

For the first 30 years, the state has first refusal if residents want to sell their homes.

Change ahead?

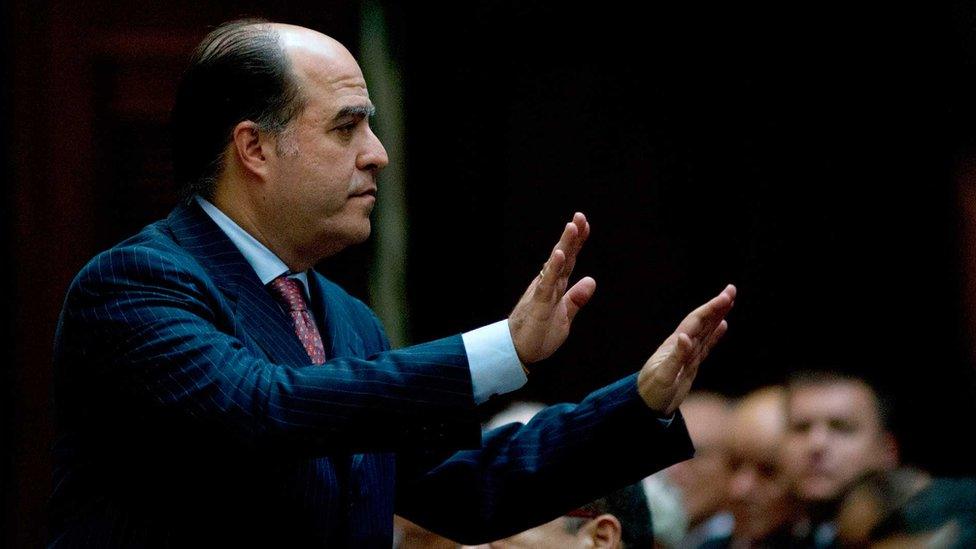

This is something opposition politician Julio Borges proposes to change.

Opposition lawmaker Julio Borges says residents should be able to decide their own future

He argues that residents are in a precarious position because they do not have full ownership rights over their homes.

"The big problem is that because the people aren't owners of the properties, they are subject to political games," he says.

"We have received complaints that people who don't support the government have been evicted from their houses."

He proposes giving all residents the title deeds to their properties at no extra cost.

Residents would continue making payments to the government but would be able to sell their properties on the open market once they were given the property's title deeds, which Mr Borges says will happen within six months.

The bill Mr Borges has proposed has already passed its first reading in the Venezuelan National Assembly, which has been dominated by the opposition since its election win last December.

Concerns

But some residents fear that a change to the law could come at a high price.

Residents fear that if landowners are compensated, they will have to pay the cost

Under Mr Borges's proposals, a commission would be set up to establish whether the owners of the land on which the houses were built need to be compensated.

This, some residents fear, could lead to the properties being revalued to include the cost of the compensation payment.

They are worried their monthly payments would rise as a result and they would be forced to take out mortgages they might not be able to afford.

"If they are successful in this plan to privatise the homes, it will be very difficult because we will never be able to afford it. We won't be able to afford it because we know that the cost that they will ask us to pay will be very, very high," says Mrs Mendivil.

Mr Borges insists his plan will not increase costs for residents but the proposal has laid bare deep divisions on the issue of public housing.

The opposition believes the state has grown too powerful and that the market should play a larger role, while the government accuses their opponents of wanting to dismantle their social programmes and privatise social housing.

'Not a business'

"The Housing Mission was not conceived as a business, but to meet the needs of human beings, citizens, who don't have anywhere to live," says pro-government assembly member Francisco Torrealba.

Marbelly Sanchez is determined to pay for her apartment, which she has painted in lively colours

He says residents already have legally binding rights that give them the "full use, possession, enjoyment and occupancy" of the properties.

"We think the aim of this law is to cash in on these properties which have been built by the state to attend to a human need.

"The hidden aim is to make it possible to mortgage the properties and we will then be going back to a time when many Venezuelans lost their homes because they couldn't pay their mortgages," Mr Torrealba alleges.

Marbelly Sanchez, a single mother of three, was re-housed on the Santa Rosa estate after her shanty-town home on a hillside collapsed.

She is also sceptical about the opposition's motives. "I don't believe that the opposition is going to give us the property rights for nothing.

"That is a lie. I have this house thanks to the president and the revolution. I will pay for it bit by bit," she says.

But Mr Borges says his plan is all about empowering residents.

"Our plan will give people ownership, liberty and power, rights which are fundamental for families to thrive."

- Published7 January 2016

- Published7 December 2015

- Published11 June 2014